MCAI Lex Vision: Compass's Strategic Use the Co-Conspirator Narrative in Antitrust Litigation

A foresight simulation on how co-conspirator allegations serve Compass’s broader strategy of institutional destabilization and platform control

I. The Pattern Beneath the Legal Claims

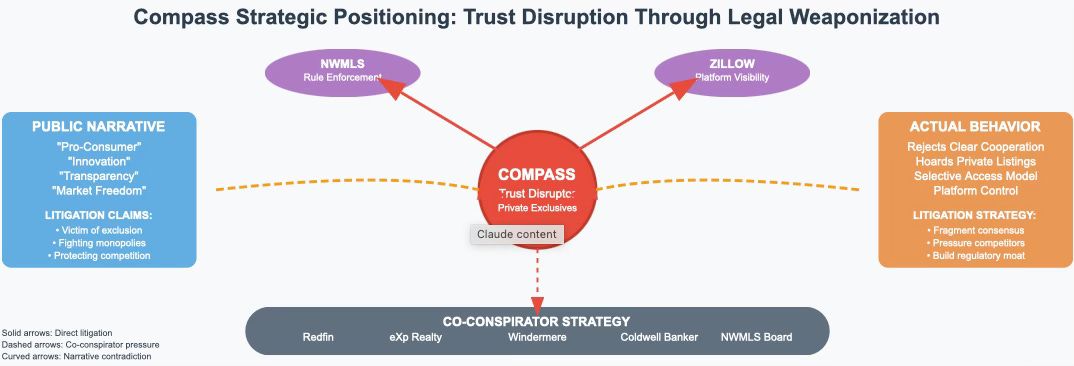

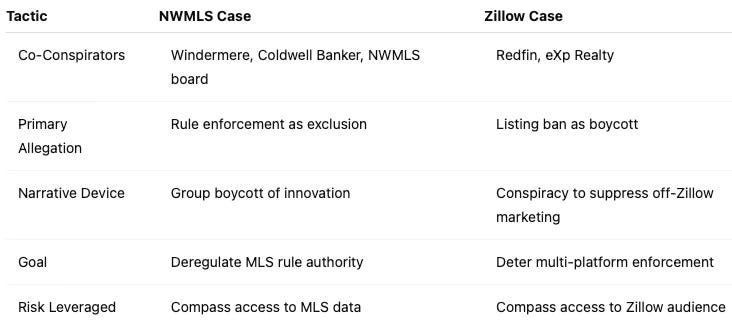

Compass’s litigation playbook reveals a deeper strategy: reshape the rules of real estate by targeting institutions that enforce transparency. Though framed as antitrust complaints, its lawsuits against NWMLS and Zillow (see MCAI Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant NWMLS, Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant Zillow) aim not to correct exclusion—but to institutionalize Compass’s own gatekeeping tactics.

In both cases, Compass presents itself as a victim of closed networks. In reality, it builds its own private walls while accusing others of collusion. It weaponizes legal language—terms like “transparency,” “choice,” and “freedom”—to justify exclusivity.

The pattern is consistent: litigate, invert, and reframe. Compass uses lawsuits not to level the field, but to fence off territory. The real goal is a regulatory moat that shields its selective access model from scrutiny.

II. The Alleged Co-Conspirators

Compass does not simply challenge institutions—it strategically casts peer firms as co-conspirators. Redfin, eXp Realty, Windermere, and Coldwell Banker are named as collaborators in exclusion, even as they promote industry norms of open listing access.

This legal framing draws from prior analysis in MCAI Lex: Chutzpah: Weaponizing Antitrust. Compass accuses others of enforcing exclusion while it defends its own private firewall. That contradiction is not incidental. It is the strategy.

Co-conspirator claims allow Compass to expand discovery and reputational pressure while avoiding formal countersuits. These allegations distort the legal picture by turning lawful transparency into implied misconduct—and they deliver multiple strategic advantages: they broaden the scope of alleged collusion without increasing Compass’s legal exposure, expand discovery leverage by targeting peer firms not formally sued, and apply reputational pressure while shielding Compass from counter-litigation. Most significantly, this framing recasts industry governance as institutional conspiracy, manipulatively undermining public confidence in shared rulemaking.

Regulators and courts will demand evidence of collusion—not just policy alignment. And as Compass disavows industry standards, it risks becoming the actual disruptor of shared access. The true target of these lawsuits is not Zillow or NWMLS—it is the legitimacy of collective rule enforcement itself.

III. Strategic Framework and Litigation Architecture

Compass’s litigation is not reactive. It is premeditated policy destabilization dressed in legal grievance. By naming “co-conspirators,” Compass disrupts alignment across MLSs and platforms. It isolates enforcers and polarizes the field.

MCAI identified three foresight hypotheses to test this pattern:

H1: Naming Redfin, eXp, Windermere, and NWMLS board members is designed to preempt industry consensus around listing transparency.

H2: The “co-conspirator” strategy is a narrative substitute for market share expansion.

H3: These lawsuits are a calculated move to trigger regulatory fragmentation and reputational recoil.

This model frames litigation not as dispute, but as structured maneuver. Compass is trying to reshape the infrastructure that defines real estate governance.

IV. Strategic and Systemic Consequences

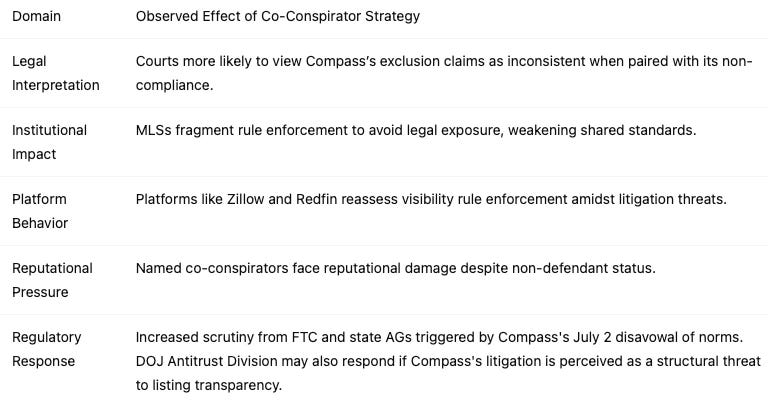

MCAI’s cultural and legal simulations reveal that Compass’s framing generated ripple effects far beyond courtrooms. As documented in MCAI Lex: #DistrustCompass: A Cultural Movement Emerges, the lawsuits catalyzed reputational distrust, institutional withdrawal, and public skepticism.

Named co-conspirators became reputational targets despite adhering to open-market policies. MLSs reconsidered enforcement alignment. Platforms delayed rule enforcement to avoid being caught in Compass’s narrative dragnet.

What began as litigation became a civic signal. Compass, once branded as a disruptor, increasingly appeared as a trust liability. The backlash was not simply rhetorical—it reshaped policy posture across institutions.

Compass’s litigation strategy not only disrupts institutions—it erodes public trust. By rejecting transparency policies while litigating in their name, Compass sends conflicting signals that courts and regulators cannot ignore. MCAI identifies this behavior as a form of “trust disruption”—not because Compass is excluded, but because it exploits cooperative systems for unilateral gain.

While many firms push against outdated norms, Compass undermines them while claiming to protect them. Its lawsuits challenge shared governance but defend a model built on selective access. Trust is not collateral damage here—it is the target.

V. Simulation Use Cases and Applications

To validate MCAI’s hypotheses, simulations were conducted using Cognitive Digital Twin foresight modeling, with scenario branches calibrated across legal precedent, institutional behavior, and reputational signal propagation. These simulations confirmed that Compass’s litigation strategy triggered instability in rule enforcement, heightened reputational exposure for peer firms, and created confusion in compliance interpretation.

Co-conspirator firms like Redfin and eXp were shown to experience policy hesitation—pressured to respond without being parties. Following Compass’s public rejection of the Clear Cooperation Policy on July 2, judicial perception models indicated a measurable drop in deference to Compass’s exclusion claims, especially where platform norms were involved.

The following simulation matrix summarizes effects across key domains:

Compass Co-Conspirator Simulation Matrix

The Department of Justice Antitrust Division, which has previously challenged coordination and listing policies in real estate, may view Compass’s strategy as an intentional destabilization of enforcement norms. Suing both NWMLS and Zillow while simultaneously abandoning the Clear Cooperation Policy positions Compass as a disruptor of market governance. If the DOJ interprets this as a structural effort to privatize listing access and discredit coordinated standards, it may open an inquiry—particularly if platform segmentation escalates across markets. Compass may walk into a mirage if it seeks safety harbor in disregarding Clear Cooperation Policy guidelines.

VI. Legal Precedents and Framework

Compass’s litigation posture cuts against all of these precedents. It conflates injury to its discretionary control with injury to the marketplace—and seeks to dismantle rules that uphold fairness under the guise of reform.

Federal courts have consistently held that antitrust law is designed to protect consumer welfare—not competitor convenience. In Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007), the Supreme Court emphasized that antitrust claims require evidence of agreement, not mere parallel conduct. Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 442 U.S. 330 (1979) established that the foundation of antitrust injury must be harm to consumers—through reduced access, higher prices, or diminished innovation.

In Continental T.V. v. GTE Sylvania, 433 U.S. 36 (1977), the Court applied the rule of reason to vertical restraints, highlighting the need for rigorous analysis of actual market effects. FTC v. Indiana Federation of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447 (1986), reaffirmed deference to self-regulatory bodies that promote transparency. And in NYNEX Corp. v. Discon, Inc., 525 U.S. 128 (1998), the Court clarified that harm to a rival firm’s strategy is not anticompetitive unless it leads to public harm.

VII. Final Assessment

Compass's litigation strategy reveals a deeper logic: antitrust is no longer a shield for fairness—it's a weapon for market capture. By naming peer firms like Redfin, eXp Realty, Windermere, and Coldwell Banker as co-conspirators while avoiding direct confrontation, Compass fragments industry consensus without triggering legal retaliation. This co-conspirator strategy allows it to weaponize transparency rhetoric while consolidating its own gatekeeping power, targeting firms that enforce the very open standards Compass rejects through its Private Exclusives model.

Courts, platforms, and regulators now face a critical choice: whether antitrust law remains tethered to consumer harm, or whether it can be perverted into a tool for strategic market manipulation. Compass no longer seeks to shape shared governance from within—it seeks to replace it entirely, using litigation to destabilize cooperative frameworks while building its own exclusive access regime. The future of transparency in real estate will be decided not by innovation rhetoric, but by whether institutions prove strong enough to reject this strategic distortion of antitrust enforcement.

Compass is not suing for fairness. It is suing for control.

Sponsor social media boost for this MCAI forecast simulation.