MCAI Market Vision: The Phase Transition in AI Infrastructure Value Capture

Why DepreciationGate, Hyperscaler Defection, and Orchestration Layer Emergence Are the Same Story

I. Executive Summary

What Is at Stake

Three seemingly unrelated stories dominated AI infrastructure discourse in late 2025. Michael Burry accused Big Tech of inflating earnings through aggressive depreciation schedules—projecting $176 billion in understated depreciation by 2028. The Wall Street Journal covered mounting competition to Nvidia from hyperscaler custom silicon. An emerging thesis argued that software orchestration layers—not hardware—will capture the decisive share of AI infrastructure value.

These are not three stories. They are one story, viewed from different angles.

The unified story: AI infrastructure is undergoing a phase transition where hardware possession no longer determines value capture. Access-layer control does. Graphics processing unit (GPU) depreciation schedules fail not because of accounting manipulation but because economic useful life collapses once inference workloads migrate to cheaper custom silicon and orchestration software abstracts hardware differences. The depreciation debate, hyperscaler silicon defection, and orchestration layer emergence are symptoms of the same underlying shift.

The stakes are large. AI hardware is a multi-hundred-billion-dollar supply chain. Hyperscalers spend $200-300 billion per year on AI infrastructure. The shift from GPUs to Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), Trainium, and custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) is the largest reallocation of capital expenditure in Big Tech’s history. Investors will misprice the entire AI sector if they treat Nvidia’s dominance as permanent. Regulators will misallocate enforcement resources if they treat hardware possession as the chokepoint for capability control. Enterprises will overpay for infrastructure if they fail to see orchestration software as the emerging locus of value capture.

About MindCast AI

MindCast AI is a predictive intelligence system designed to run high-fidelity foresight simulations using proprietary Cognitive Digital Twins. Rather than describing what might happen in the future, MindCast AI models how institutions, markets, and technologies behave under pressure—revealing patterns, vulnerabilities, and advantage windows long before they surface in public discourse.

The system treats organizations as dynamic cognitive actors whose decisions evolve through incentives, constraints, and adaptation. This allows MindCast AI to generate realistic forward paths rather than abstract scenarios. When the Wall Street Journal writes about GPU depreciation schedules, it describes accounting policy. When MindCast AI models the same question, it asks: what happens when Nvidia’s economic model collides with hyperscaler incentives to build purpose-built inference silicon at 30-44% lower total cost of ownership (TCO)? The answer is not an accounting dispute. The answer is a phase transition in value capture.

Cognitive Digital Twin Methodology

At the center of the MindCast AI platform are Cognitive Digital Twins (CDTs)—detailed behavioral models that mirror how companies, regulators, investors, and infrastructure ecosystems actually make decisions. CDTs integrate financial structures, technological trajectories, institutional habits, and strategic incentives. When MindCast AI runs foresight simulations across multiple twins at once, it identifies where outcomes converge, where divergence begins, and where small shifts create outsized effects.

The CDT approach reduces the transaction cost of thinking about complex systems and replaces speculation with structured, testable predictions. MindCast AI is built for environments where the pace of change outstrips traditional analysis. The system evaluates not only what actors intend but how they behave under uncertainty and constraint. By translating complexity into coherent futures, MindCast AI gives decision-makers a clearer picture of risk, opportunity, and timing—making foresight a practical tool for real-world intervention rather than a theoretical exercise.

The Three-Actor CDT Model: This analysis requires only three Cognitive Digital Twins to model the AI infrastructure phase transition.

Nvidia is the incumbent whose economic model depends on GPU useful life assumptions—the belief that GPUs retain value through inference repurposing after they become obsolete for frontier training.

Hyperscalers (Google, Amazon, Meta) make custom silicon decisions that determine whether inference workloads remain on GPUs or migrate to purpose-built alternatives.

The Orchestration Layer is the software abstraction that makes hardware fungible and shifts value capture from silicon to access.

The interaction of these three actors—not accounting policy, not competitive dynamics in isolation—explains why depreciation schedules break. Note that the foresight simulation lessons from this publication extend beyond Nvidia.

The Foresight Simulation

Core thesis: GPU depreciation schedules fail because GPUs lose economic relevance long before they lose physical life. The Wall Street Journal’s December 2025 coverage lacks foresight because it never sees the access-layer transition driving that collapse. Michael Burry is directionally correct that something is wrong with AI infrastructure valuations—but wrong about the mechanism. The problem is not accounting fraud. The problem is that the market prices hardware dominance as if access-layer dynamics do not exist.

The foresight generates three testable predictions:

GPU economic life breaks early (2026-2028 window) even if physical life is 5-7 years. Hyperscaler purpose-built silicon captures inference workloads faster than depreciation schedules assume.

Hyperscaler silicon and orchestration layers absorb inference before GPUs complete their depreciation cycle. The ‘value cascade’ argument—that aging training GPUs become inference workhorses—fails because inference is migrating to TPUs, Trainium, and ASICs at 30-50% lower TCO.

Investors who model Nvidia as a hardware-dominant company mis-price risk because advantage duration is being determined at the software access layer. Training remains Nvidia’s stronghold. Inference—the larger and faster-growing market—does not.

Foresight is the ability to see that the depreciation debate, silicon defection, and orchestration emergence are the same causal process—not three disconnected stories. The CDT model makes this visible by revealing how incentives propagate across the three actors.

Article Roadmap

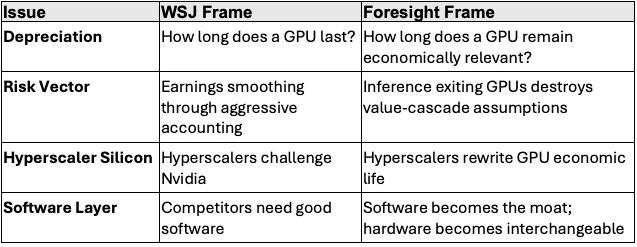

Section II critiques the Wall Street Journal’s December 8, 2025 article on GPU depreciation, identifying four analytical failures that stem from treating hardware as the unit of competitive advantage.

Section III examines Michael Burry’s depreciation fraud thesis, explaining why he is directionally correct but magnitude-wrong. The section distinguishes physical durability, economic obsolescence, and strategic optionality—three concepts that ‘useful life’ conflates.

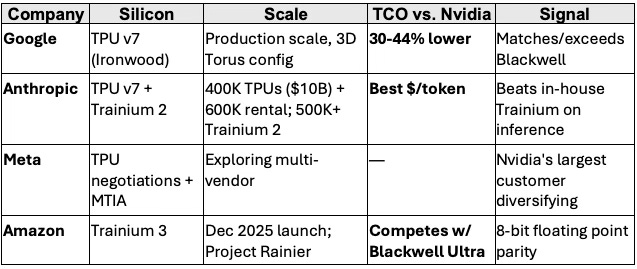

Section IV documents the hyperscaler defection pattern: Google TPU v7 at 30-44% lower TCO than Nvidia Blackwell, Anthropic’s $10 billion TPU commitment, Meta’s multi-vendor diversification, Amazon’s Trainium 3 launch. Four of the five largest AI infrastructure buyers are building or committing to alternative silicon at production scale.

Section V explains why Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) lock-in is eroding and why orchestration software—not hardware—is becoming the primary locus of value capture. The section identifies the coordination cost problem that creates market opportunity for unified orchestration layers.

Section VI translates the analysis into investment implications: Nvidia repricing risk, orchestration layer opportunity, and evaluation criteria for companies positioned in the emerging access-layer economy.

Section VII addresses regulatory considerations: consistency asymmetry in depreciation policy, systemic risk concentration, and disclosure adequacy.

Section VIII defines the 2026-2028 window when the phase transition completes: hyperscaler silicon reaches production scale, depreciation schedules hit their back half, inference economics force enterprise decisions, and software abstraction layers mature.

Section IX concludes with the unified answer: access-layer control determines advantage duration, not hardware possession. The CDT model is parsimonious—three actors explain the entire transition.

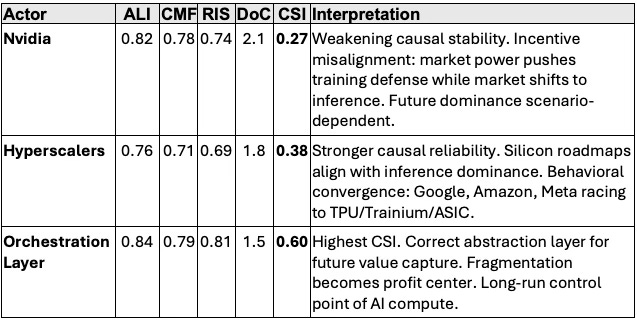

Foresight Simulation: CDT Metrics

MindCast AI’s Foresight Simulation quantifies why depreciation schedules break and where value migrates. The table below shows CDT metrics for all three actors. Key metrics: Action-Language Integrity (ALI) measures statement-behavior consistency. Cognitive-Motor Fidelity (CMF) measures execution reliability. Resonance Integrity Score (RIS) measures decision coherence. Degree of Complexity (DoC) scales difficulty. Causal Signal Integrity (CSI) is the trust score: CSI = (ALI + CMF + RIS) / DoC.

Key insight: CSI increases as you move up the access layer (0.27 → 0.38 → 0.60). Causal integrity is highest where value capture is migrating.

Cross-CDT Foresight Simulation Prediction (2026-2028)

Hyperscaler silicon adoption accelerates → GPU inference value collapses → Orchestration becomes the dominant control layer → Nvidia retreats to training-dominance + platform strategy. GPU economic life shortens to 2-3 years for competitive workloads. Orchestration platforms gain decisive access-layer power. Hyperscalers force industry-wide repricing of hardware-centric narratives.

With the CDT model established, the analysis now turns to current market discourse—beginning with the Wall Street Journal’s recent coverage and why it misses the structural shift.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on AI market foresight simulation. See prior publications: Foresight Simulation of NVIDIA H200 China Policy Exploit Vectors (Dec 2025); The Global Innovation Trap (Nov 2025); The Department of Justice, China, and the Future of Chip Enforcement (Nov 2025); Lessons from Aerospace: What High-Velocity Markets Teach About AI Export Risk (Nov 2025); Predictive Cognitive AI and the AI Infrastructure Ecosystem (Oct 2025); NVIDIA NVQLink Validation (Oct 2025); Nvidia’s Moat vs. AI Datacenter Infrastructure-Customized Competitors (Aug 2025). Foresight simulation library relevance details in relevant sections below.

II. How the WSJ Article Lacks Foresight

The Wall Street Journal’s December 8, 2025 article ‘The Accounting Uproar Over How Fast an AI Chip Depreciates‘ by Jonathan Weil is technically correct yet strategically blind. The blind spots cluster into four failures:

Summary: The WSJ writes news. MindCast AI models systems. The WSJ sees accounting. We see access-layer economics erasing a hardware-based worldview.

The table above captures the analytical gap. Each failure stems from a common root: treating hardware as the unit of competitive advantage. The WSJ conflates physical durability with strategic usefulness, never recognizing that a six-year depreciation schedule is incompatible with a 12-24 month obsolescence cycle in inference. The article frames the debate as ‘how fast does hardware depreciate’ when the real question is ‘how fast does the economic model that justified the hardware break down.’

When inference workloads migrate to TPUs and Trainium at 30-44% lower TCO, the ‘repurposed GPU’ that was supposed to justify years 4-6 of depreciation becomes a stranded asset. When Google, Amazon, and Meta all invest billions in purpose-built inference silicon, they aren’t ‘challenging’ Nvidia—they are systematically removing the inference workloads that GPU depreciation schedules assume will absorb aging hardware. The competitive dynamic isn’t market share—it’s the collapse of an economic assumption baked into accounting policy.

The depreciation debate is not about whether companies are cheating—it’s about whether the economic assumptions underlying depreciation schedules survive contact with a world where inference migrates to cheaper silicon and orchestration software makes hardware fungible. Model the three CDTs, and the accounting question answers itself.

The loudest voice in the depreciation debate comes from outside mainstream financial journalism. The next section examines why that voice—Michael Burry’s—is directionally correct but analytically incomplete.

III. The Depreciation Debate: What Burry Gets Right and Wrong

The debate intensified when Michael Burry weighed in. Burry is the hedge fund manager who famously predicted and profited from the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis—a bet chronicled in Michael Lewis’s book The Big Short and the subsequent film starring Christian Bale. His track record of identifying systemic financial risks before they become consensus gives his critiques unusual weight on Wall Street.

Burry’s November 2025 critique accused hyperscalers of ‘one of the more common frauds of the modern era.’ The alleged fraud: extending the useful life of AI servers and GPUs from 3-4 years to 5-6 years, thereby understating depreciation and inflating reported earnings. Burry disclosed short positions against Nvidia and Palantir. Shortly thereafter, he deregistered his fund Scion Asset Management and stepped away from managing outside money. His estimates project $176 billion in understated depreciation between 2026 and 2028, inflating combined earnings by roughly 20%.

Burry is directionally correct but magnitude-wrong. The depreciation question is real; the fraud framing is hyperbolic. Here’s why:

The accounting is legal, disclosed, and audited. Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon all disclose their depreciation policy changes in Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings. Auditors validate engineering assessments of useful life. The policies are aggressive, not fraudulent. Cash flow—the metric that actually matters for solvency and capital allocation—remains unaffected. Depreciation schedules shift when earnings are recognized, not whether value exists.

The magnitude is overstated relative to total profitability. Meta’s depreciation expense ran approximately $13 billion in the first nine months of 2025; the useful-life extension reduced that by $2.3 billion. Against pretax profits exceeding $60 billion, the impact is material but not transformative. Depreciation expenses are skyrocketing even with the accounting moves—from $10 billion quarterly across major hyperscalers in late 2023 to nearly $22 billion by Q3 2024, projected to reach $30 billion by late 2025.

The real risk is return on investment, not depreciation schedules. Weak return on capital, pricing pressure from alternative silicon, and eventual asset write-downs pose far greater threats than depreciation timing. Hyperscalers are spending hundreds of billions on infrastructure whose revenue model remains largely speculative for non-search/advertising applications. Whether they depreciate over four years or six years matters less than whether the infrastructure generates returns at all.

The Useful Life Question Nobody Can Answer

The deeper problem is that ‘useful life’ conflates three distinct concepts that diverge in the AI hardware context:

Physical durability: How long before the hardware fails? Answer: 5-7 years with proper cooling and maintenance. GPUs don’t physically disintegrate on Nvidia’s product cadence.

Economic obsolescence: How long before newer hardware renders the asset uncompetitive? Answer: 12-24 months for frontier training workloads. Nvidia now releases new architectures every 12-18 months. Blackwell offers 40x Hopper performance; Rubin will offer another 3x improvement. A six-year-old GPU is four generations behind.

Strategic optionality: How long before the asset loses all productive use cases? Answer: potentially 6+ years if older chips can be repurposed for inference workloads. This is the ‘value cascade’ argument—yesterday’s training chip becomes today’s inference workhorse.

The hyperscalers’ 5-6 year depreciation schedules implicitly bet on strategic optionality—that inference workloads will absorb aging hardware and extend productive life beyond the training-competitive window. This bet may prove correct. But it faces a challenge the depreciation debate largely ignores: inference workloads are migrating to purpose-built silicon that makes repurposed GPUs economically irrelevant.

How fast is this migration happening? The next section documents the hyperscaler defection pattern—and the velocity is faster than most observers recognize.

IV. The Hyperscaler Defection Pattern

See as reference: The Global Innovation Trap (Nov 2025) — Advantage window compression from 8-10 years to 2-4 years; H100 case study showing $40-45B value transfer as exclusivity collapsed; validates hyperscaler silicon closing performance gap faster than depreciation schedules assume; Nvidia’s Moat vs. AI Datacenter Infrastructure-Customized Competitors (Aug 2025) — Identified structural vulnerability in Nvidia’s moat 4 months before depreciation debate; predicted TCO parity by late 2025; validated by TPU v7 benchmarks showing 30-44% advantage

The Wall Street Journal’s December 2025 coverage of Nvidia’s competitive challenges understates the velocity of change. The hyperscaler defection pattern has accelerated dramatically since mid-2025. Total cost of ownership (TCO) advantages are driving the shift:

Key insight: Four of the five largest AI infrastructure buyers are building or committing to alternative silicon. The hyperscaler defection is not experimental—it is at production scale with clear TCO advantages.

The Inference Economics Forcing Function

The competitive shift is driven by inference economics, not training requirements. Training remains Nvidia’s stronghold—the combination of CUDA ecosystem depth, NVLink interconnects, and software optimization makes GPU clusters difficult to displace for frontier model development. But training is a shrinking fraction of AI compute demand.

Inference workloads—the actual deployment of trained models to serve users—now dominate AI compute consumption and are growing faster than training demand. Inference is also more price-sensitive, more predictable in workload characteristics, and more amenable to purpose-built silicon optimization. Google’s TPUs, Amazon’s Inferentia and Trainium, and Meta’s MTIA all target inference efficiency specifically.

The inference migration creates a structural problem for the ‘value cascade’ depreciation argument. If older GPUs were going to be repurposed for inference workloads, those workloads are now increasingly served by purpose-built ASICs at 30-50% lower TCO. The inference market that was supposed to extend GPU useful life is being captured by alternative silicon before the GPUs reach their cascade phase.

The hyperscaler defection pattern explains why depreciation schedules break. But it doesn’t explain where value migrates once hardware becomes fungible. The next section addresses that question: software orchestration.

V. The Software Orchestration Imperative

See as reference: Predictive Cognitive AI and the AI Infrastructure Ecosystem (Oct 2025) — Established “access-layer value capture” thesis; predicted value migration from silicon to software abstraction as hardware commoditized; Kubernetes precedent and network effects follow from this framework; NVIDIA NVQLink Validation (Oct 2025) — Analyzed Nvidia’s software-first strategy; predicted Nvidia would try to control access-layer transition; identifies where independent providers can compete (vendor-neutral multi-cloud deployment)

The depreciation debate and hyperscaler competition stories share a common blind spot: both focus on hardware while the decisive value capture layer is shifting to software. Specifically, AI orchestration and inference software that abstracts workload management from underlying silicon.

The WSJ article on Nvidia competition correctly noted that competitors ‘must not only deliver compelling AI chips, but provide an integrated Software + Hardware stack.’ The observation understates the strategic implications. The software layer is not merely an enabler of hardware adoption—it is becoming the primary locus of value capture and competitive moat.

A. Why CUDA Lock-In Is Eroding

Nvidia’s CUDA ecosystem represents 18 years of developer investment—3.5 million AI developers worldwide code in CUDA. Switching to alternative silicon requires rewriting substantial codebases. CUDA lock-in has been Nvidia’s most durable competitive advantage.

But CUDA lock-in operates at the wrong layer. CUDA binds developers to Nvidia hardware for trainingworkloads where code complexity is highest. Inference workloads—increasingly the majority of AI compute—operate at higher abstraction layers where hardware-specific optimization matters less. A TensorRT-optimized model can be converted to run on alternative inference engines; the conversion cost is falling as inference frameworks mature.

More importantly, enterprises deploying AI at scale face a portfolio problem: they need optionality across silicon vendors, but each vendor’s software stack creates lock-in. The coordination cost of managing multiple inference environments—Nvidia TensorRT, Google JAX/JetStream, AWS Neuron SDK, Intel OpenVINO—grows faster than the compute cost savings from multi-vendor sourcing.

B. The Kubernetes Precedent

The pattern has a recent historical analog. In 2014-2018, container orchestration faced the same fragmentation: Docker Swarm, Apache Mesos, and proprietary cloud solutions each created vendor lock-in. Kubernetes emerged as the neutral abstraction layer that let enterprises deploy across AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure without rewriting deployment logic. By 2020, Kubernetes had become the de facto standard, and the companies that built tooling around Kubernetes (Datadog, HashiCorp, Confluent) captured substantial value—often more than the underlying infrastructure providers.

AI inference orchestration is following the same trajectory. The question is not whether an abstraction layer emerges—it will. The question is whether that layer will be controlled by hyperscalers (who have incentive to favor their own silicon) or by independent providers (who have incentive to remain neutral). The multi-cloud reality—85% of enterprises now use two or more cloud providers—creates structural demand for vendor-neutral orchestration.

C. Network Effects and Switching Costs

Orchestration layers exhibit strong network effects. As more enterprises standardize on a given orchestration platform, the ecosystem of integrations, trained engineers, and deployment patterns grows. This creates switching costs independent of the underlying hardware—exactly the dynamic that made CUDA sticky for training workloads. The difference is that orchestration-layer switching costs bind enterprises to a software abstraction rather than to a silicon vendor.

The value capture pattern becomes clearer: hardware vendors compete on price and performance; orchestration vendors compete on breadth of integration and ease of use. As hardware becomes more commoditized (TPUs, Trainium, and GPUs converging on similar price-performance for inference), orchestration differentiation increases. The layer that abstracts the commodity captures the margin.

D. Why Hyperscalers Cannot Easily Capture This Layer

Google, Amazon, and Microsoft all offer AI orchestration tools (Vertex AI, SageMaker, Azure ML). But these tools have structural limitations for multi-cloud deployment. Google has limited incentive to optimize orchestration for Trainium; Amazon has limited incentive to optimize for TPUs. Each hyperscaler’s orchestration tooling favors its own silicon—creating the coordination cost problem that independent orchestration addresses.

The multi-cloud reality creates a structural opening. Enterprises running inference across multiple clouds need a Switzerland—an orchestration layer that treats all hardware as first-class citizens. Independent orchestration providers can occupy this position in ways hyperscalers structurally cannot. This is not a market failure; it is an architectural inevitability created by the incentive structure of vertically integrated cloud providers.

E. The Value Capture Pattern

Companies positioning in the orchestration layer provide unified AI orchestration and inference software. The software enables deployment across Nvidia GPUs, Google TPUs, AWS Trainium, Intel Gaudi, and other accelerators from a single control plane. These companies capture value regardless of which hardware wins. Whether enterprises deploy on Nvidia, Google, Amazon, or a mix, they need software that manages the complexity. The orchestration provider becomes the Switzerland of AI silicon—neutral, essential, and increasingly valuable as hardware diversity grows.

The risk for independent orchestration providers is that hyperscalers build this capability themselves (Google’s JetStream, AWS’s Neuron SDK) or that open-source alternatives (vLLM, Ray Serve) commoditize the layer before independent vendors can capture durable margin. The multi-cloud, hybrid deployment reality creates space for independent orchestration players—but the window to establish market position is likely 2025-2027, before hyperscaler tooling or open-source alternatives mature.

Understanding where value migrates is analytically interesting. Understanding how to position capital for that migration is actionable. The next section translates the structural analysis into investment implications.

VI. Investment Implications

See as reference: The Department of Justice, China, and the Future of Chip Enforcement (Nov 2025) — Regulatory attention concentrates on visible chokepoints while structural shifts occur elsewhere; depreciation regulation follows same pattern—SEC focuses on accounting compliance while access-layer migration falls outside purview; Foresight Simulation of NVIDIA H200 China Policy Exploit Vectors (Dec 2025) — Export control enforcement faces same access-layer challenge as depreciation regulation; concentrated market structure creates correlated policy vulnerabilities

The phase transition from hardware-centric to software-centric value capture has specific implications for how investors should price AI infrastructure assets:

A. Nvidia Repricing Risk

Nvidia remains the dominant AI infrastructure company with approximately 80% market share in AI accelerators. But the market prices Nvidia as if CUDA lock-in and training dominance extend indefinitely into inference workloads. If inference migrates to purpose-built silicon at the pace the hyperscaler commitments suggest, Nvidia’s addressable market contracts even as AI compute demand grows.

The depreciation debate becomes relevant here not as an earnings-quality concern but as a signal of market expectations. Hyperscalers extending GPU useful lives to 5-6 years are implicitly betting that inference repurposing will sustain hardware value. If that bet fails—if inference workloads move to TPUs and Trainium faster than depreciation schedules assume—impairment charges and accelerated depreciation revisions become likely in 2026-2028.

B. Orchestration Layer Opportunity

Software companies positioning in the AI orchestration layer merit increased attention. The investment case rests on two structural tailwinds: hardware fragmentation increases coordination costs that orchestration software addresses, and orchestration layers exhibit network effects as more enterprises standardize deployment workflows.

Key evaluation criteria include multi-silicon support breadth (how many accelerator types can the platform manage?), enterprise deployment scale (are Fortune 500 companies using it in production?), and integration with hyperscaler-native tooling (can it work alongside Google’s Vertex AI, AWS SageMaker, and Azure ML?).

Note: The independent orchestration layer remains an emerging category. Most current multi-silicon abstraction occurs through hyperscaler-native tooling or open-source frameworks (MLflow, Ray, vLLM). The investment thesis anticipates consolidation as coordination costs rise and hardware diversity increases—but specific independent winners have not yet emerged at scale.

Beyond investment implications, the phase transition raises questions for policymakers. The depreciation debate has attracted regulatory attention—but is that attention focused on the right questions?

VII. Regulatory Considerations

See as reference: Lessons from Aerospace: What High-Velocity Markets Teach About AI Export Risk (Nov 2025) — Established advantage window compression framework from aerospace/semiconductor history; 2026-2028 window reflects compressed timeline; strategic positioning decisions made in 2025 determine value capture

Should regulators care about depreciation schedules? Modestly. The accounting is compliant with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and disclosed. Three considerations merit regulatory attention:

Consistency asymmetry: Companies can extend useful lives when it flatters earnings but face no requirement to shorten them when technological obsolescence accelerates. Amazon’s 2024 decision to shorten server useful life from six to five years—the opposite of the industry trend—suggests at least one hyperscaler sees reality differently. Regulators might require sensitivity analysis disclosure showing earnings impact under alternative depreciation assumptions.

Systemic risk concentration: When five companies control the AI infrastructure build-out and all use similar depreciation assumptions validated by similar auditors, revision risk becomes correlated. A single hyperscaler taking an impairment charge could trigger industry-wide reassessment.

Disclosure adequacy: The earnings per share (EPS) impact of depreciation policy changes is disclosed in footnotes, but most retail investors don’t read 10-Ks. Enhanced Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) disclosure of depreciation policy sensitivity analysis might improve market pricing efficiency.

These regulatory considerations become more pressing as the phase transition accelerates. The critical question is timing: when does the transition complete, and what markers signal its progress?

VIII. The 2026-2028 Window

The phase transition in AI infrastructure value capture will largely complete between 2026 and 2028. Several converging dynamics define this window:

Hyperscaler silicon reaches production scale. Google’s TPU v7, Amazon’s Trainium 3, and Meta’s next-generation Meta Training and Inference Accelerator (MTIA) will all be in volume deployment by 2026. The ‘custom silicon is unproven’ objection expires.

Depreciation schedules hit their back half. GPUs deployed in 2022-2024 under 5-6 year depreciation schedules enter years 3-4 by 2026-2027. If inference repurposing fails to materialize as expected, impairment charges become likely.

Inference economics force enterprise decisions. Enterprises currently running inference on Nvidia hardware will face clear TCO comparisons with alternative silicon. The 30-40% cost advantage of TPUs and Trainium at scale is difficult to ignore when inference costs dominate AI operational budgets.

Software abstraction layers mature. Orchestration platforms that today support 3-4 accelerator types will support 8-10 by 2027. The coordination cost of multi-vendor strategies falls, accelerating hardware diversification.

Strategic Positioning for the Transition

For investors, the 2026-2028 window suggests reducing exposure to pure-play hardware companies with concentrated customer bases and increasing exposure to software companies positioned in the orchestration layer. For enterprises, the window suggests accelerating evaluation of multi-silicon strategies and orchestration platforms that reduce switching costs.

For Nvidia specifically, the transition is not existential—training workloads remain GPU-dominant, and Nvidia’s software capabilities (Dynamo, TensorRT, CUDA ecosystem) provide defensive moats. But the inference market that was supposed to provide long-term growth may increasingly belong to purpose-built silicon and the software layers that orchestrate it.

IX. Conclusion

The CDT model is parsimonious: three actors explain the entire transition. Nvidia’s economic model assumes GPUs retain value through inference repurposing. Hyperscalers are systematically removing inference workloads from that assumption. The Orchestration Layer makes the hardware decision increasingly irrelevant by abstracting workload management from silicon. When these three actors interact, depreciation schedules built on hardware-centric value capture fail—not because of accounting manipulation, but because the economic model underlying the accounting no longer holds.

Michael Burry is right that something is wrong with AI infrastructure valuations. He’s wrong about the mechanism. The problem isn’t accounting fraud—it’s that the market prices hardware dominance as if access-layer dynamics don’t exist. The question is no longer which hardware wins. It’s who controls the access layer that determines whether hardware matters at all.

Appendix: MindCast AI CDT Metrics and Vision Functions

CDT Metrics

ALI – Action-Language Integrity: Measures how consistent an actor’s statements are with their underlying behavior and incentives. High ALI indicates credible communication; low ALI signals narrative-behavior gaps that distort prediction and coordination.

CMF – Cognitive-Motor Fidelity: Evaluates how well an organization executes on its stated strategy. High CMF means the institution reliably translates decisions into action; low CMF reflects execution drift, bottlenecks, or misalignment between teams.

RIS – Resonance Integrity Score: Assesses whether decisions maintain coherence over time and across contexts. Higher RIS indicates durable reasoning patterns, while lower RIS reflects volatility, reactive decision cycles, or internal contradictions.

DoC – Degree of Complexity: Represents how many interacting variables influence an outcome. Higher DoC reduces causal clarity and increases uncertainty. It functions as the denominator in CSI, scaling the difficulty of trustworthy inference.

CSI – Causal Signal Integrity: A trust score that tests whether a causal explanation is structurally sound. CSI = (ALI + CMF + RIS) / DoC, meaning even strong signals degrade if the system’s complexity is high. High CSI indicates a reliable causal path; low CSI flags fragile or misleading interpretations.

Vision Functions

Market Vision: Analyzes supply, demand, cost structures, and competitive dynamics. It helps identify where value will migrate as the environment shifts—especially in fast-moving infrastructure markets.

Causation Vision: Tests whether the assumed causal relationships in a system actually hold. It identifies breaks, confounding forces, and hidden accelerators that change how outcomes unfold.

SBC Vision – Strategic Behavioral & Cognitive Analysis: Explains how incentives convert into real-world actions. It models behavioral drift, coordination breakdowns, and tipping points, showing where stated strategies diverge from revealed preferences.

ICP Vision – Institutional Cognitive Plasticity: Measures how quickly an institution updates its internal architecture when external conditions change. High ICP means rapid adaptation; low ICP signals legacy inertia that leads to strategic blind spots.

Innovation Vision: Evaluates the maturity, novelty, and structural potential of new technologies or approaches. It highlights where elegant, simplified design becomes a competitive advantage.

Long-Range Scenario Analysis: Projects multi-year scenarios and maps the strategic consequences of different choices. It highlights the branching structure of futures, allowing comparison between optimal decisions and likely institutional behavior.