MCAI Legacy Vision: The Coordination Problem Hiding Inside Every Family Enterprise

A Legacy Innovation Framework from Game Theory, Behavioral Economics, Cognitive Digital Twins

See also in the MindCast AI Strategic Behavioral Cognitive (SBC) framework series, applying game theory, behavioral economics, cognitive digital twins: MCAI Market Vision: The Economic Strategy Behind Licensing (Dec 2025), MCAI Cultural Innovation Vision: The Economic Architecture Behind Malcolm Gladwell’s Worldview (Dec 2025).

MCAI Economics Vision: Synthesis in National Innovation Behavioral Economics and Strategic Behavioral Coordination (Dec 2025) discusses the relationship between MindCast AI’s two fall 2025 economic frameworks.

Executive Summary

Legacy Innovation is one of the most misunderstood strategic challenges in business. Family enterprises do not behave like corporations governed by quarterly incentives or like startups driven by rapid experimentation. They behave like multigenerational games in which power, identity, trust, and narrative continuity shape every decision. Their long-term success depends not on technology adoption alone, but on how generations coordinate, how incentives align across time, and how leaders interpret one another’s signals under uncertainty.

This requires a different analytical lens. Traditional strategy tools cannot capture the forces that govern a 100-year enterprise. To understand legacy organizations — and to help them innovate — we integrate game theory, behavioral economics, and MindCast AI Cognitive Digital Twins (CDTs).

Game theory maps the strategic structure: the cooperation and defection incentives between founding generations, successors, non-family CEOs, and governance bodies. These interactions form repeated games, signaling environments, and succession equilibria that determine whether families adapt or fracture.

Behavioral economics exposes the predictable distortions inside those structures — dynasty bias, narrative loss aversion, and identity-driven risk aversion. These biases explain why families often fail to act even when the equilibrium clearly requires innovation.

MindCast AI proprietary Cognitive Digital Twins complete the picture by modeling the actual agents inside the system: their incentives, fears, trust levels, temporal horizons, and susceptibility to bias. CDTs allow us to simulate intergenerational coordination, succession pathways, innovation timing, and leadership defection risk with fidelity that traditional frameworks cannot match. CDTs synthesize:

Game theory → strategic structure

Behavioral economics → biases

Bounded rationality → decision constraints

Unlike traditional models, CDTs capture incentive structures, temporal horizons, trust relationships, narrative anchors, and signal interpretation—enabling projection of coordination dynamics before they emerge in real decisions.

Together, these three components create a precise model of how legacy organizations behave and evolve. Foresight enters here: by running MindCast AI CDT interactions forward through multiple generational cycles, we can project coordination patterns, identify innovation windows, and forecast where governance will strengthen or fracture. This turns legacy analysis from a descriptive exercise into a predictive one.

This paper demonstrates how multigenerational coordination — not capital or technology — is the primary determinant of long-term strategic resilience.

I. The 100-Year Problem

In 1987, a third-generation manufacturing family faced a critical decision. The founder’s original facilities required either significant modernization or complete replacement with automated systems. The financial analysis pointed clearly toward automation: reduced costs, competitive positioning, operational efficiency.

The chairman supported incremental modernization. The CEO advocated for full automation. Neither would yield. The board couldn’t break the deadlock. Two years passed. Competitors automated. Market share eroded. Eventually, the family sold at a discount.

The conventional diagnosis: poor strategic planning.

The actual problem: a coordination failure between generations operating under incompatible time horizons, trust assumptions, and identity narratives.

The chairman’s time horizon extended to preserving what the founder had built and maintaining employment in the founder’s hometown. The CEO’s time horizon focused on competitive survival over the next decade. The chairman heard “automation” as “abandoning our people.” The CEO heard “modernization” as “accepting irrelevance.”

Neither was wrong about their objective. But they couldn’t coordinate on a shared strategic frame.

This is the 100-year problem.

Family enterprises face strategic pressures that differ fundamentally from those confronting conventional firms. Their decisions unfold within multigenerational frameworks where identity, reputation, and family cohesion often outweigh financial optimization. This creates a strategic environment shaped less by competition in time and more by coordination across time.

A public corporation operates on quarterly cycles with clear principal-agent relationships. Incentives align through compensation structures. Information flows through standardized reporting. Control changes through market mechanisms. Strategy follows predictable patterns.

A family enterprise operates on generational cycles with overlapping authority. Incentives misalign across time horizons. Information flows through family relationships and implicit understandings. Control changes through biological events. Strategy depends on relationship architecture.

The distinction matters because traditional corporate strategy assumes you can change leadership to execute new strategy. In family enterprises, changing strategy often requires changing family relationships—which may be impossible within decision timeframes.

Consider the structural differences:

In corporations:

CEO has clear authority bounded by board oversight

Strategy execution measured in quarters and fiscal years

Capital allocation follows ROI optimization

Leadership succession managed through search and selection

Innovation depends on capital and talent access

In family enterprises:

Authority dispersed across generations with ambiguous boundaries

Strategy execution measured in decades and generational transitions

Capital allocation balances optimization against identity preservation

Leadership succession constrained by family dynamics and narrative continuity

Innovation depends on coordination architecture

The second set of constraints is invisible to traditional strategy frameworks but determinative of outcomes.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Legacy Innovation foresight simulations.

II. The Missing Coordination Layer

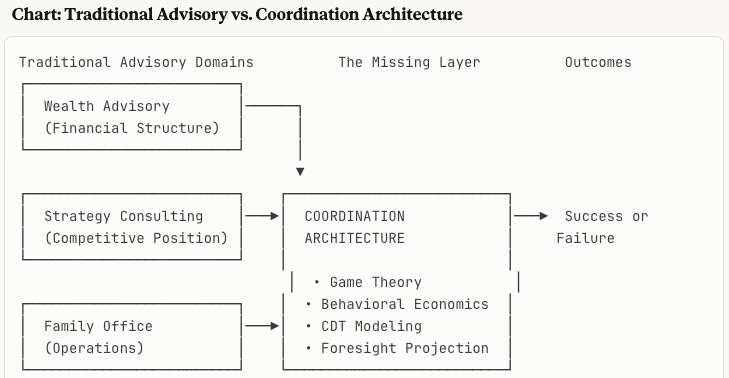

When families seek strategic guidance, they typically engage wealth advisors who optimize financial structures, strategy consultants who analyze competitive positioning, and family offices that coordinate services.

These are necessary—but insufficient for the 100-year problem.

What Financial Optimization Misses

Wealth advisors excel at structuring estates to minimize tax burden across generations. They model asset allocation strategies that balance growth, income, and preservation. They design trust structures that protect assets and provide for future generations.

What they cannot model: whether the structures they design create incentive alignment between generations or trigger defection dynamics.

A common wealth advisory structure creates separate trusts for each family branch, providing equal distributions but independent control. This optimizes for fairness and autonomy.

The coordination consequence: Each branch now faces the prisoner’s dilemma. If the enterprise requires capital reinvestment, each branch can defect (take distributions) while hoping others cooperate (reinvest). When all branches reason identically, coordination collapses.

The financial structure is tax-efficient but coordination-toxic.

What Strategy Consulting Misses

Strategy consultants can identify which markets to enter and which capabilities to build. They can develop transformation roadmaps with detailed financial projections showing revenue growth and margin expansion.

What they cannot assess: whether the family’s coordination architecture allows them to execute the recommended strategy.

A common consulting recommendation: “Appoint a non-family CEO with technology expertise to lead digital transformation.”

The behavioral consequence: If the family has high dynasty bias and narrative loss aversion, they will interview technology CEOs but ultimately select someone who “understands our culture”—which becomes code for “won’t challenge our identity.” The strategy fails not from bad design but from selection bias the consultants didn’t model.

The strategic analysis is sound but behaviorally unrealistic.

What Administrative Coordination Misses

Family offices coordinate complexity brilliantly: consolidating accounts, managing properties, coordinating philanthropy, ensuring the founder’s preferences are maintained seamlessly.

What they cannot reveal: whether the family’s coordination patterns are sustainable across the next succession transition.

A common family office structure: The founder maintains final authority on all major decisions. The family office implements efficiently. Successors have operational roles but defer to the founder on strategy.

The succession consequence: When the founder exits, there is no established coordination protocol. The family office can execute decisions—but no one has clear authority to make decisions. The governance vacuum triggers either paralysis or conflict.

The operational excellence masks structural fragility.

The Coordination Gap

The gap is not in financial expertise, strategic analysis, or operational excellence. The gap is in coordination architecture analysis.

Traditional advisors optimize within their domains. But legacy enterprises succeed or fail based on whether generations can coordinate across domains—and traditional frameworks don’t model this layer.

This is where game theory, behavioral economics, and Cognitive Digital Twins become essential. Not as replacements for traditional advisory, but as the coordination layer that determines whether financial structures support strategic execution, whether strategic recommendations are behaviorally feasible, and whether operational systems remain coherent through succession transitions.

III. The Analytical Framework

A. Game Theory: Mapping Strategic Structure

Family enterprises are repeated games played across generations with imperfect information and overlapping authority. Every major decision involves multiple actors with different payoff structures.

The game-theoretic foundation for understanding these dynamics draws from John Nash’s work on equilibrium behavior in systems with competing incentives (Equilibrium Points in N-Person Games, 1950; Non-Cooperative Games, 1951). Nash demonstrated that when multiple actors with different objectives interact strategically, stable outcomes (equilibria) emerge based on the structure of incentives—not on cooperation or goodwill. In family enterprises, these equilibria determine whether coordination or fragmentation becomes the stable state.

Thomas Schelling’s analysis of strategic behavior under uncertainty (The Strategy of Conflict, 1960) provides the framework for understanding how families signal intentions and interpret responses. Schelling showed that commitment mechanisms, focal points, and credible signaling are essential when actors cannot directly communicate intentions or when communication is unreliable. Founders releasing control gradually send signals that successors must interpret. Misinterpreted signals cascade into coordination failures.

Core game-theoretic concepts in family enterprises:

Repeated Games: Family interactions aren’t single transactions—they’re ongoing relationships where today’s cooperation builds trust for tomorrow’s coordination, and today’s defection triggers punishment cycles that last decades. The shadow of the future (the expectation of continued interaction) can sustain cooperation even when immediate incentives favor defection.

Signaling Under Uncertainty: Founders signal intentions through actions. Successors interpret these signals. A founder gradually releasing control might intend to signal “I trust you” but the successor hears “I don’t think you’re ready.” These interpretive gaps create coordination failures even when all parties prefer alignment.

Coalition Formation: When succession involves multiple potential leaders, they form coalitions that determine which strategies are possible. These coalitions shift based on how each member interprets others’ intentions under ambiguity. The family becomes a game within a game.

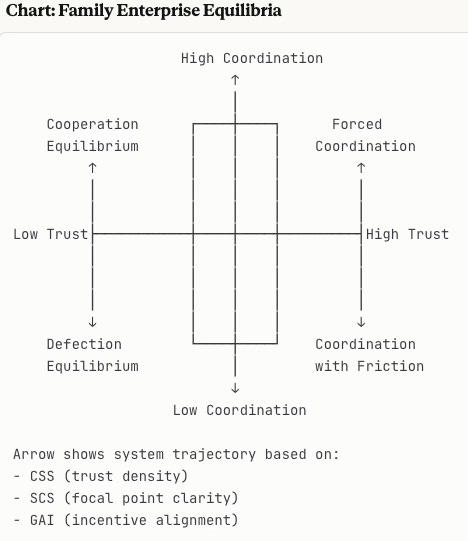

Equilibrium Analysis: Given the incentive structures, what stable outcomes exist? Family enterprises can reach high-coordination equilibria (collective stewardship) or low-coordination equilibria (fragmentation and defection). Understanding which equilibrium the family trends toward reveals intervention opportunities before the system locks into an inferior stable state.

B. Behavioral Economics: Predictable Distortions

Even when game-theory equilibrium points toward cooperation, behavioral biases can prevent families from reaching it. The behavioral-economic framework reveals why families systematically deviate from strategies that would maximize collective value.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s prospect theory (Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk, 1979; Choices, Values, and Frames, 1984) demonstrated that humans weight losses more heavily than equivalent gains, and evaluate outcomes relative to reference points rather than absolute states. Kahneman’s later synthesis (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011) established the architecture of cognitive bias that shapes decision-making under uncertainty.

Richard Thaler’s work on behavioral economics (Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics, 2015; Nudge, 2008) translated these insights into practical applications, showing how predictable irrationalities shape real-world economic decisions. Thaler demonstrated that understanding bias architecture allows us to design choice environments (and governance structures) that channel behavior productively.

Core behavioral biases in family enterprises:

Dynasty Bias: The cognitive distortion that makes family continuity feel like moral imperative rather than one possible outcome. Families overweight “preserving what we built” relative to “building what’s needed next.” This maps directly to Kahneman’s loss aversion: the family’s reference point is the founder’s legacy, and any change feels like loss even when it creates future gain.

Narrative Loss Aversion: Families weight potential narrative damage (violating heritage) more heavily than potential narrative gains (creating new legacy). This asymmetry explains excessive conservatism: the downside of change feels larger than the upside. The family’s identity becomes the reference point, and innovation feels like identity loss.

Identity-Driven Risk Aversion: When business decisions threaten family identity, risk aversion intensifies beyond what financial analysis would suggest. This question—”If we do this, are we still us?”—can block optimal transactions. The family exhibits extreme risk aversion in the domain of identity (Kahneman’s “losses loom larger than gains”) even while taking substantial financial risks.

Endowment Effect Across Generations: Thaler’s endowment effect—people value what they possess more than identical items they don’t possess—operates across generations in family enterprises. Successors inherit not just assets but psychological ownership of the founder’s narrative. This inflates the subjective value of “how we’ve always done it” relative to alternative approaches.

These biases don’t make families irrational. They make families rational about different objectives than corporations. A corporation maximizes shareholder value. A family enterprise maximizes the joint product of financial performance, identity continuity, and relationship preservation. The optimization is harder, and behavioral biases make it harder still.

C. Cognitive Digital Twins: Modeling Actual Agents

Game theory maps structure. Behavioral economics maps distortions. But to project actual outcomes, MindCast AI must model the specific actors inside the system.

MindCast AI’s Cognitive Digital Twins are proprietary modeling technology that operationalizes foundational research in game theory, behavioral economics, and bounded rationality. The intellectual foundation draws from Herbert Simon’s work on bounded rationality. Simon demonstrated that human decision-making operates under constraints: limited information, limited computational capacity, and limited time. Rather than optimizing globally, humans “satisfice”—they search for solutions that meet aspiration levels rather than maximizing expected utility.

MindCast AI synthesizes these academic foundations—game theory (Nash, Schelling), behavioral economics (Kahneman, Thaler), and bounded rationality (Simon)—into Cognitive Digital Twins: computational models that simulate how specific actors with constrained cognition, behavioral biases, and finite time horizons make decisions within family enterprise systems. We model bounded rationality constrained by specific information sets, cognitive biases, time horizons, and trust relationships. This creates tractable models that capture actual decision-making rather than idealized optimization.

A Cognitive Digital Twin captures:

Incentive structure: What does this actor optimize for? (Not always financial—often identity, relationships, or narrative)

Time horizon: Over what period do they measure success? (15 years for founders, 30 years for successors, 7 years for non-family executives)

Trust radius: Whom do they believe? Whom do they doubt? (Trust density determines information flow and coordination capacity)

Narrative anchors: What stories define their identity? (These stories become constraints on acceptable strategies)

Bias susceptibility: Which behavioral distortions affect their decisions? (Dynasty bias, loss aversion, endowment effects)

Signal interpretation: How do they read others’ actions under ambiguity? (The interpretive gap often exceeds the actual disagreement)

Satisficing criteria: What outcomes meet their aspiration levels? (Simon’s bounded rationality: actors don’t optimize, they satisfice)

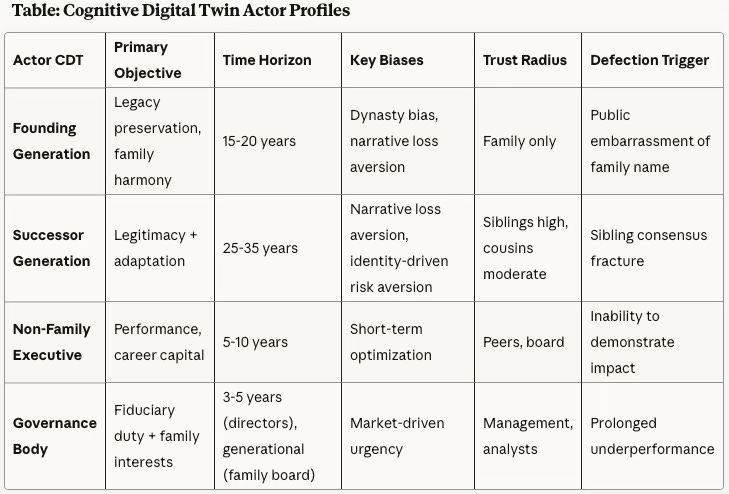

For a typical family enterprise, MindCast AI models four primary CDT categories:

Founding Generation CDT: Optimizes for legacy preservation and family harmony. Long time horizon (15-20 years to grandchildren). High dynasty bias and narrative loss aversion. Interprets innovation proposals through “does this threaten what we are?” Satisficing criteria: successors demonstrate respect for heritage while maintaining family cohesion.

Successor Generation CDT: Optimizes for legitimacy while adapting to change. Medium-long time horizon (25-35 years). Caught between respecting heritage and proving capability. Interprets signals from both founders (am I loyal enough?) and markets (am I competent enough?). Satisficing criteria: gain operational authority without fracturing family relationships.

Non-Family Executive CDT: Optimizes for performance and career capital. Shorter time horizon (5-10 years). Wants clear authority but faces ambiguous governance. Interprets family dynamics as constraints on execution. Satisficing criteria: demonstrate measurable impact within tenure window while navigating family politics.

Governance Body CDT: Optimizes for fiduciary duty balanced against family interests. Variable time horizons (board members: 3-5 years; family governors: generational). Faces tension between market demands (transform now) and family capacity (coordinate first). Satisficing criteria: maintain performance within acceptable ranges while preserving family ownership.

By simulating interactions between these CDTs, coordination dynamics become visible before they emerge in real decisions. The CDT framework doesn’t predict what families should do (optimization models). It projects what families will do given their bounded rationality, biased decision-making, and constrained information.

Illustrative CDT Simulation Sequence

A founder CDT proposes delaying major investment until the next generational transition. The successor CDT interprets this as a lack of confidence in their readiness, which reduces trust density and shifts their satisficing threshold toward asserting authority sooner. The non-family executive CDT interprets the mixed signals as a warning that the family may not unify around long-term commitments, increasing their defection-risk rating. The governance CDT attempts to reconcile these interpretations but lacks a focal point for coordination, lowering the governance-alignment index.

Across simulated cycles, small interpretive gaps widen into structural misalignment: trust density declines, authority boundaries blur, and no actor sees a path to satisficing without triggering conflict. The foresight signal is not a calendar prediction but a structural one: under these conditions, the system becomes unable to coordinate on investment decisions requiring multi-actor commitment. CDT simulations reveal these coordination thresholds before they surface in real decisions.

D. Foresight: Projecting System Trajectories

The power of integrating game theory, behavioral economics, and CDT modeling is that it produces foresight—structured scenario projection that reveals where the system is already trending.

MindCast AI Foresight Engine Summary

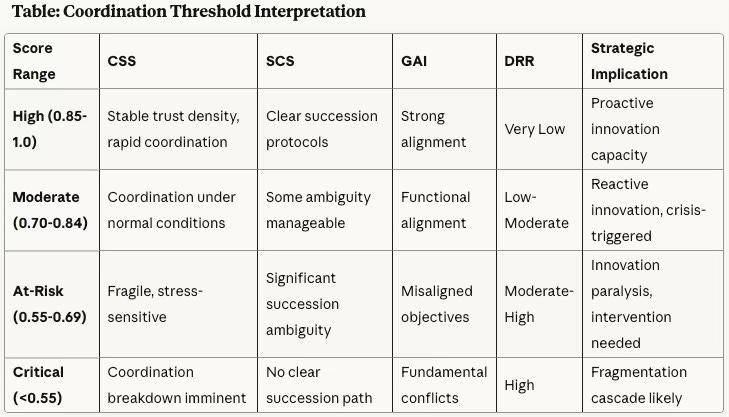

Foresight is generated by simulating repeated interactions among Founder, Successor, Governance, and Non-Family Executive CDTs under varying incentive structures, trust patterns, and narrative constraints. These simulation runs produce structural scores—coordination stability, succession clarity, governance alignment, defection risk, and innovation-window timing—that capture the system’s underlying trajectory.

Foresight is validated through historical pattern alignment, consistency with game-theory equilibria and behavioral-economic constraints, and scenario-stress testing to see which trajectories persist across different inputs.

Families use the resulting foresight to time governance interventions, redesign incentive and ownership structures, and determine which strategies are executable with current coordination architecture—and which require coordination repair before execution becomes possible.

How foresight is validated:

MindCast AI does not claim to predict specific events decades out. We identify structurally consistent trajectories—patterns that emerge when incentives (Nash), signal interpretation (Schelling), behavioral biases (Kahneman, Thaler), and bounded rationality (Simon) interact across generations.

Validation mechanisms:

Historical Pattern Alignment: Do projections match patterns observed in comparable legacy enterprises? We test CDT models against historical cases where outcomes are known, checking whether the model would have projected the actual trajectory.

Equilibrium Consistency: Do projected outcomes align with game-theory equilibria and behavioral-economic principles? Nash equilibria constrain possible outcomes—projections that violate equilibrium stability are rejected.

Scenario Robustness: When we vary inputs (succession timing, market shocks, governance changes), which outcomes remain stable? Those reveal durable dynamics driven by structural forces rather than contingent events.

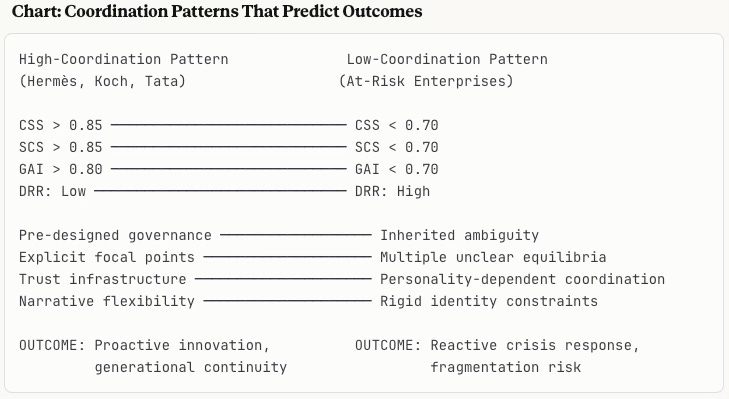

Testable elements:

Coordination Stability Score (CSS): Trust density, incentive alignment, and communication clarity across generational CDTs. Measures whether the family can reach and maintain cooperation equilibria.

Succession Clarity Score (SCS): Ambiguity in leadership transition protocols and authority distribution. Low SCS predicts coordination breakdown at succession because no focal point exists (Schelling).

Governance Alignment Index (GAI): Coherence between family objectives, board duties, and executive incentives. Misalignment creates multi-principal problems where executives face contradictory optimization targets.

Defection Risk Rating (DRR): Likelihood that actors prioritize personal interests over collective coordination. High DRR indicates the family is near a defection equilibrium in the repeated game.

Innovation Window Timing (IWT): Whether innovation capacity is proactive (family can coordinate before crisis) or reactive (family coordinates only under external pressure). Reactive IWT indicates low coordination capacity.

Falsifiability framework:

Outcomes must remain stable across scenario variation, align with historical patterns, and adhere to game-theoretic and behavioral-economic constraints. If projections fail these tests, the model parameters are revised. The model can fail—which is what makes it credible.

IV. Comparative Architecture: Four Legacy Archetypes

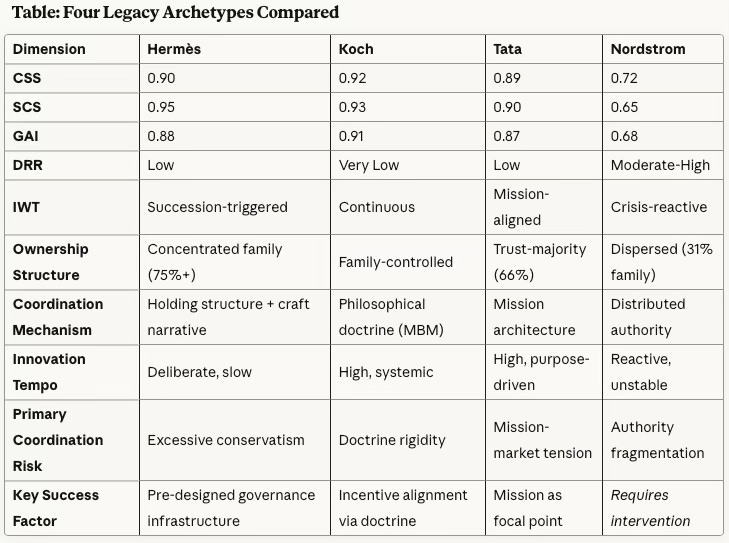

These four enterprises represent distinct archetypes of legacy governance and innovation. Each exhibits unique combinations of cohesion, incentives, and narrative identity. By analyzing them comparatively, we reveal how structural differences drive divergent innovation trajectories.

Hermès: Cohesive Conservatism

Coordination Scores:

CSS: 0.90 | SCS: 0.95 | GAI: 0.88 | DRR: Low | IWT: Succession-triggered, deliberate

Architecture: Hermès maintains coordination through concentrated family ownership (75%+ consolidated in holding structure), clear craft narrative, and deliberate slow-innovation tempo. The founding generation established a cultural doctrine around craftsmanship supremacy. Successors have preserved this with minimal deviation. Non-family executives operate within clearly defined narrative boundaries.

Coordination Mechanism: When LVMH threatened control in 2010, over 50 family descendants consolidated shares with 20-year lock-ups within weeks. This rapid coordination response was possible only because the governance architecture had been designed for exactly this scenario. High CSS and SCS meant the family could reach a cooperation equilibrium (Nash) under time pressure, using pre-established focal points (Schelling) for coordination.

Innovation Pattern: Innovation occurs slowly and deliberately, triggered by succession transitions rather than market pressure. Each generation reinterprets craft heritage for contemporary conditions without threatening core identity. Digital commerce adoption was delayed but executed within narrative continuity once the family aligned. The family’s bounded rationality (Simon) focuses on maintaining quality standards—they satisfice on innovation timing to preserve coordination capacity.

Why This Architecture Works: The family designed governance for coordination before crisis. Concentrated ownership, clear succession protocols, and strong narrative identity create structural stability that allows innovation when the family chooses, not when markets demand.

Koch Industries: Incentive-System Architecture

Coordination Scores:

CSS: 0.92 | SCS: 0.93 | GAI: 0.91 | DRR: Very Low | IWT: Continuous, incentive-driven

Architecture: Koch operates as a philosophical system, not a personality-driven enterprise. Governance cohesion originates from Market-Based Management doctrine rather than lineage alone. Successors absorb this framework early, minimizing interpretive drift across generations. Non-family leaders integrate seamlessly because the system rewards alignment, clarity, and execution.

Coordination Mechanism: The family established explicit principles that govern decision-making, resource allocation, and leadership selection. These principles create predictable coordination patterns because all actors optimize against the same framework (reducing the signal interpretation problems Schelling identified). When market conditions shift, the family adapts rapidly because the doctrine itself values adaptation.

Innovation Pattern: Innovation throughput is high and continuous because the incentive system rewards value creation regardless of source. The family doesn’t face the typical dynasty bias (family members must create value, not inherit positions) or narrative loss aversion (the doctrine is about principles, not specific practices). By structuring incentives to align individual and collective interests, Koch reaches stable cooperation equilibria with minimal coordination friction.

Why This Architecture Works: By encoding family values into operational principles rather than personal authority, Koch created coordination infrastructure that persists across generations. The CDT profile reveals minimal behavioral distortion because the incentive architecture counters typical family enterprise biases. This is behavioral economics (Thaler) applied to governance design: the choice architecture channels bounded rationality toward productive outcomes.

Tata Group: Mission-Based Stewardship

Coordination Scores:

CSS: 0.89 | SCS: 0.90 | GAI: 0.87 | DRR: Low | IWT: Mission-aligned, trust-cycle driven

Architecture: Tata exemplifies mission-based stewardship, where the Tata Trusts (which own 66% of Tata Sons) form the backbone of long-term coherence. The family’s moral architecture—combining economic modernization with social responsibility—creates coordination through shared purpose rather than ownership control. Successors operate within a mandate that transcends personal interest.

Coordination Mechanism: Non-family CEOs hold substantial operational power but remain anchored to the mission narrative. This allows the family to access professional management capability without triggering the typical trust erosion. The governance structure separates operational authority (professional management) from mission stewardship (family/trusts), reducing coordination complexity. The mission serves as a focal point (Schelling) that enables coordination even when specific strategic disagreements emerge.

Innovation Pattern: Innovation accelerates when aligned with mission. Digital transformation, sustainability initiatives, and market expansion all proceed rapidly when framed as serving India’s development. Innovation that conflicts with mission faces resistance regardless of financial merits. The bounded rationality (Simon) of Tata’s governance focuses on mission consistency—financial optimization is secondary to mission alignment.

Why This Architecture Works: The mission provides a stable coordination point across generations and between family and non-family leaders. Everyone optimizes against the same objective function, reducing the signal misinterpretation that typically plagues family enterprises. The mission architecture also counters narrative loss aversion (Kahneman): change doesn’t threaten identity when framed as mission fulfillment.

Nordstrom: Market-Pressured Adaptation

Coordination Scores:

CSS: 0.72 | SCS: 0.65 | GAI: 0.68 | DRR: Moderate-High | IWT: Market-pressure triggered, unstable

Architecture: Nordstrom illustrates the market-pressured adaptation archetype, where a strong service narrative must be reconciled with retail disruption and public-market demands. The founding identity anchors cultural continuity, but successor generations face sharper innovation pressures. Public ownership creates board dynamics that add coordination complexity.

Coordination Mechanism: The family maintains significant ownership (31%) and operational presence across multiple generations, but authority is distributed without clear primacy. The co-president structure reflects this coordination ambiguity—sufficient alignment to maintain family presence, insufficient clarity to execute rapid transformation. In game-theoretic terms (Nash), the family operates near a mixed-strategy equilibrium: sometimes coordinating, sometimes fragmenting, depending on external pressure.

Innovation Pattern: Innovation occurs reactively in response to competitive threats rather than proactively from strategic choice. Windows open during crises but close when immediate pressure subsides. Digital transformation proceeded incrementally because the family couldn’t coordinate on whether digital represented heritage extension or heritage abandonment. This is classic narrative loss aversion (Kahneman): the perceived loss from potentially violating service heritage outweighs the potential gain from digital leadership.

Coordination Challenge: The 2017 privatization attempt revealed the structural limits. The family couldn’t align on valuation, timing, post-transaction governance, or strategic vision simultaneously. Not because of capability gaps, but because the coordination architecture couldn’t handle the complexity load. CSS below 0.75 and SCS below 0.70 predict exactly this outcome: without clear focal points (Schelling) for coordination and with dispersed authority creating multiple possible equilibria (Nash), the family cannot reach agreement under time pressure.

Why This Architecture Struggles: Dispersed ownership across four generations, succession ambiguity, public-market pressure, and moderate trust density create coordination friction. The family maintains presence but not the governance infrastructure that would enable proactive transformation. The bounded rationality (Simon) of multiple actors with different time horizons, trust levels, and narrative interpretations makes satisficing difficult—no single outcome satisfies all actors’ aspiration levels simultaneously.

V. Cross-System Insights

Comparing these four archetypes reveals consistent patterns grounded in game theory, behavioral economics, and bounded rationality:

What High-Coordination Families Share

Explicit Governance Design: Hermès, Koch, and Tata all designed governance for coordination before crisis. They established clear protocols for decision-making, authority boundaries, and succession transitions. This creates focal points (Schelling) that enable coordination when disagreement emerges. Nordstrom inherited governance ambiguity, which left the family without coordination mechanisms when tested.

Coordination Infrastructure: High-performing families build coordination mechanisms: holding structures (Hermès), doctrinal frameworks (Koch), mission architecture (Tata). These create stable equilibria (Nash) that persist across generations. Without infrastructure, coordination depends on personality—which fails at succession because new actors lack the shared history that enabled implicit coordination.

Narrative Flexibility: Successful families evolve narrative identity deliberately. Koch’s Market-Based Management, Tata’s mission adaptation, and Hermès’s craft reinterpretation all show families updating heritage for contemporary conditions. This counters narrative loss aversion (Kahneman): by reframing change as continuity, families reduce the psychological loss associated with adaptation. Rigid narratives become coordination constraints because they make all change feel like identity loss.

Trust Density: CSS above 0.85 indicates families that have built trust infrastructure—regular communication, transparent decision-making, demonstrated follow-through on commitments. Trust enables coordination under uncertainty because it reduces the information asymmetry and signal misinterpretation (Schelling) that prevent families from reaching cooperation equilibria (Nash). Trust is not culture—it’s the accumulated history of coordination success that makes future coordination feasible.

What Predicts Fragmentation

Succession Ambiguity: SCS below 0.70 predicts coordination failure at succession transitions. When authority is unclear, families lack focal points (Schelling) for coordinating on leadership selection. Multiple possible equilibria exist (Nash), but no mechanism for selecting among them. Ambiguity compounds across generations because each succession further fragments authority without creating new coordination mechanisms.

Incentive Misalignment: When ownership structures create prisoner’s dilemmas (each branch benefits from others’ reinvestment while taking distributions), defection becomes the dominant strategy (Nash). High DRR indicates structural incentives favor defection over cooperation in the repeated game. Families reach low-coordination equilibria not from ill will but from rational response to incentive architecture.

Governance-Market Mismatch: Public ownership adds coordination complexity. Families face quarterly pressure while operating on generational timelines. GAI below 0.75 indicates boards and families optimize against different objective functions, creating multi-principal problems. Non-family executives face conflicting signals about what success means, making satisficing (Simon) difficult—no action satisfies both principals’ aspiration levels.

Reactive Innovation: When IWT is crisis-triggered rather than strategy-driven, families lose competitive position. They innovate only when forced, which means they innovate late. This reflects low coordination capacity: the family can only overcome narrative loss aversion (Kahneman) and dynasty bias when external pressure is extreme. Proactive innovation requires sufficient trust density and governance clarity to coordinate before crisis forces coordination.

VI. Strategic Implications

Understanding coordination architecture through the lens of game theory (Nash, Schelling), behavioral economics (Kahneman, Thaler), and bounded rationality (Simon) reveals several strategic principles:

1. Governance Design Precedes Strategy

High-coordination families establish governance infrastructure before strategic inflection points. They clarify decision authorities, succession protocols, and coordination mechanisms during stable periods—not during crises. This creates focal points (Schelling) that enable rapid coordination when time pressure emerges. Infrastructure design allows families to reach cooperation equilibria (Nash) efficiently rather than searching for coordination mechanisms during crises.

2. Coordination Capacity Is the Binding Constraint

Families fail not from lack of capital, strategy, or talent. They fail because their coordination architecture cannot execute the strategies their resources could support. The bounded rationality (Simon) of multiple actors with different time horizons, biases, and incentives creates coordination limits that bind before resource constraints. The most important strategic question becomes: “Can we coordinate to execute this?”

3. Behavioral Architecture Shapes Outcomes

Dynasty bias, narrative loss aversion, and identity-driven risk aversion (all grounded in Kahneman and Thaler’s behavioral economics) aren’t personality flaws—they’re structural features of family enterprises. Successful families design governance that channels these biases productively (like Koch’s incentive system or Tata’s mission framework) rather than fighting them directly. This is Thaler’s nudge architecture applied to family governance: accept that actors are biased, design choice environments that make productive outcomes easier.

4. Trust Is Infrastructure, Not Culture

Trust density (measured in CSS) comes from governance design: transparent communication, demonstrated follow-through, explicit protocols. It’s not about liking each other—it’s about predictable coordination patterns that reduce signal misinterpretation (Schelling) and enable cooperation equilibria (Nash). Trust is the accumulated history of successful coordination that makes future coordination feasible under uncertainty.

5. Succession Is Coordination Architecture Testing

Every succession transition stress-tests the family’s coordination capacity. Families with SCS above 0.80 navigate transitions smoothly because they have focal points (Schelling) and clear equilibrium selection mechanisms (Nash). Families below 0.70 face coordination breakdown because succession creates multiple possible equilibria with no mechanism for choosing among them. Succession clarity isn’t about identifying the best leader—it’s about establishing protocols that preserve coordination regardless of who leads.

VII. Conclusion

The 100-year problem is fundamentally a coordination problem. Family enterprises succeed when they build governance architecture that enables generations to coordinate under uncertainty, align incentives across time horizons, and adapt narrative identity to strategic realities.

Traditional advisory frameworks optimize financial structures, competitive strategies, and operational excellence. But these optimizations fail if the family cannot coordinate to execute them.

The integrated framework reveals why:

Game theory (Nash, Schelling) shows that families face repeated games with multiple equilibria. Without governance infrastructure that creates focal points and sustains cooperation, families drift toward fragmentation equilibria even when all actors prefer coordination.

Behavioral economics (Kahneman, Thaler) exposes the predictable biases—dynasty bias, narrative loss aversion, identity-driven risk aversion—that prevent families from reaching optimal equilibria even when they understand the game structure.

Cognitive Digital Twins (grounded in Simon’s bounded rationality) model how specific actors with limited information, constrained cognition, and finite time make decisions that satisfice rather than optimize. CDT interactions reveal coordination breakpoints before they emerge in real decisions.

Together, they create a precise model of how legacy organizations behave and evolve. This is the coordination layer that determines long-term resilience.

Families that understand their coordination architecture can design for durability. They can identify where governance intervention is required, when succession transitions should occur, which innovations are executable now versus later, and how to integrate professional management without fracturing trust.

The most successful legacy enterprises treat coordination as engineerable infrastructure, not cultural happenstance.

The 100-year problem requires 100-year thinking. This framework makes it analyzable.

References

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Nash, J. (1950). Equilibrium Points in N-Person Games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 36(1), 48-49.

Nash, J. (1951). Non-Cooperative Games. Annals of Mathematics, 54(2), 286-295.

Schelling, T. (1960). The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press.

Simon, H. (1947). Administrative Behavior. Macmillan.

Simon, H. (1957). Models of Man: Social and Rational. Wiley.

Thaler, R. (2015). Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. W.W. Norton & Company.

Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1984). Choices, Values, and Frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341-350.