MCAI AI Lex Vision: Chutzpah, Compass v. NWMLS

Weaponizing Antitrust — for Profit, Not Consumers

See integration of this simulation in MindCast AI Antitrust Vision: Brief of MindCast AI LLC as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant NWMLS

Executive Summary

The following AI foresight simulation is part of an ongoing series conducted by MindCast AI LLC, using predictive modeling to assess the legal, market, and narrative trajectories of Compass Inc. v. Northwest Multiple Listing Service. Filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, the lawsuit challenges NWMLS's ban on "office exclusive" listings—properties that are marketed internally within a brokerage before appearing on the public MLS. Compass claims that this rule violates federal antitrust law by restraining competition and limiting seller freedom.

Compass inverts antitrust law to protect exclusivity, assuming that harm to Compass is equivalent to harm to consumers.

By reframing its legal grievance as a public benefit, Compass seeks to defend a business model built around selective listing exposure. Yet the central tension remains: the firm is invoking antitrust doctrine—designed to protect market openness—to preserve a tactic that inherently limits access.

Two additional frames offer background context on the deeper strategic implications of Compass’s move. First, the lawsuit can be seen not as an attempt to reform antitrust law, but rather as a strategic maneuver to preserve opacity in a market increasingly driven by radical transparency. From this perspective, Compass's goal is not systemic legal change but brand self-preservation, pushing back against post-NAR reforms that emphasize simultaneous, open listing access.

Second, Compass is not acting as a coalition leader but as a lone operator defending its own brand architecture. While other firms may quietly rely on office exclusives, none have joined Compass publicly. This signals Compass’s reputational isolation and reveals that even those who might benefit from a Compass victory are unwilling to share in the public risk.

As this case evolves, MindCast AI will continue to deliver simulation-based insights across Legal Vision, Narrative Economics, Market Strategy, and Public Trust calibration—offering structured foresight not just into who wins, but how the system interprets the win.

I. Case Background

The Northwest Multiple Listing Service (NWMLS) is one of the largest member-owned real estate listing databases in the United States, serving brokers and agents throughout Washington state. As a self-regulatory organization, NWMLS enforces rules that ensure simultaneous access to property listings across its network, aiming to provide transparency and uniformity for both agents and consumers. It plays a pivotal role in standardizing listing practices across the Seattle metropolitan area and surrounding regions.

Compass alleges that NWMLS’s ban on office exclusive listings—where properties are initially marketed only within a single brokerage—violates Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. According to Compass, the rule unreasonably restrains trade by prohibiting agents from using a strategic marketing tool that benefits sellers who want discretion, pricing control, or targeted exposure before going public. For example, an agent might hold a listing internally for a week to gauge interest from trusted buyers before listing it publicly—giving Compass agents first access while shielding the property from broader market scrutiny. In high-end markets, this tactic is often used to cultivate a sense of exclusivity or protect a seller’s privacy. Compass argues that by blocking such tactics, NWMLS is reducing competition, interfering with broker autonomy, and limiting seller choice.

The lawsuit seeks monetary damages and injunctive relief that would compel NWMLS to eliminate its rule and allow brokerages like Compass to reintroduce office exclusives in Washington’s competitive real estate market. Compass frames the restriction not as a consumer protection measure, but as an outdated constraint that hinders innovation and harms the ability of agents to serve clients effectively.

What’s at Stake:

While Compass frames the issue as broker flexibility, the implications reach far beyond internal discretion. If office exclusives are reinstated, MLS listing uniformity would erode—particularly in residential real estate. Buyers could face delayed or restricted access to new listings, and sellers might be steered toward marketing strategies that benefit brokerage networks more than open market dynamics.

Compass presents a private brokerage strategy as if it were a public rights issue—a move that confuses self-interest for systemic injustice.

II. Legal Significance and Strategic Risk

This lawsuit tests the boundary of antitrust logic: whether a policy that promotes universal access can itself be considered anti-competitive. The legal weakness in Compass's claim lies in the difficulty of proving consumer harm—a cornerstone of antitrust litigation. Courts typically defer to MLSs as self-regulating entities unless there is clear, systemic market exclusion.

Compass is also an aggressive player that relies heavily on narrative framing. The company describes itself as a technology firm, though much of its technology appears aimed at solving structural limitations in scale and coordination—tools designed to manufacture the operational heft it has not yet organically achieved. This brand of self-reinvention allows Compass to present itself as both an innovator and an underdog, even while deploying the litigation leverage of an incumbent.

The lawsuit also comes on the heels of Compass’s recent acquisition spree, through which it expanded its geographic reach and agent network significantly. Seen in this context, the antitrust case functions as market expansion strategy 2.0—a legal maneuver to open tightly regulated listing environments where Compass can then deploy its scale advantage to dominate exclusive inventory. If successful, the suit would not only dismantle listing uniformity in regions like Seattle but enable Compass to concentrate high-value listings within its own broker ecosystem.

Compass wraps expansionist ambition in the rhetoric of innovation, hoping the court will mistake market capture for market freedom.

III. Industry Positioning and Strategic Contrast

Compass’s legal strategy places it in stark contrast to other major real estate platforms. Redfin has consistently aligned itself with transparency, consumer-first practices, and post-NAR listing reforms. Zillow has gone even further by banning office exclusive listings from its platform altogether, making it clear that it sees selective access as a threat to consumer trust and market integrity.

In contrast, Compass has opted for litigation over adaptation—framing a private listing tactic as a public good. Its lawsuit draws a line between firms leaning into openness and those leveraging legal systems to preserve internal control.

While these firms have taken differing public stances, others—including Sotheby’s, Windermere, and Coldwell Banker—have chosen silence. Whether out of caution, alignment, or institutional detachment, their lack of engagement reinforces the perception that Compass is acting alone.

Compass calls itself a disruptor, but its peers have disrupted more by staying out of court and aligned with transparency.

IV. Industry Silence Explained

The silence is strategic. Other firms may benefit quietly from office exclusives but prefer not to stake public trust or legal exposure on defending them. Compass’s aggressive litigation has turned a quiet practice into a public risk, prompting institutional actors to step back, observe, and let Compass bear the reputational and legal consequences alone.

Notably, neither Zillow nor Redfin—two of Compass's most prominent competitors—have joined or supported the lawsuit. Zillow has explicitly opposed private listing tactics by banning office exclusives from its platform, while Redfin has reaffirmed its commitment to transparency and consumer access. Other national brokerages, such as RE/MAX and Coldwell Banker, have made no public statements, reinforcing the perception that Compass stands alone in its legal and narrative strategy.

Compass isn’t leading a movement—it’s walking alone, and the rest of the industry is letting it.

V. Consumer Impact Forecast

Before turning to consumer impact, it is worth noting that Compass has filed this lawsuit unilaterally. No other brokerage has joined as a co-plaintiff or signaled shared legal harm. This further underscores Compass’s assumption that its own strategic limitations equate to structural market injury—an argument that courts may regard with skepticism.

Consumers—especially buyers—are unlikely to sympathize with Compass’s position. Office exclusives reduce listing visibility and may exacerbate perceptions of insider access or unfairness. While some sellers appreciate pricing control and discretion, the broader market sentiment favors transparency, especially in a post-NAR legal environment.

Compass’s core legal argument conflates harm to its business model with harm to the public. This framing is structurally weak under antitrust law, which requires evidence of diminished consumer welfare—such as higher prices, restricted access, or reduced innovation. Compass does not convincingly demonstrate that the ban on office exclusives injures consumers; instead, it asserts that limits on broker discretion reduce competition. The argument pivots on a narrow conception of “competition” defined not by consumer outcome, but by the company's own tactical flexibility. Courts may view this approach as self-referential, not market-defining.

Compass speaks of consumer choice, but what it really defends is the broker’s privilege to operate in the shadows.

VI. Legal Framework and Precedents

A. Doctrinal Weaknesses

Consumer Welfare Standard (Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 1979): Modern antitrust law focuses on consumer harm—not harm to competitors or business models. Compass’s claim focuses on its internal restrictions, not any demonstrable injury to consumer welfare (such as higher prices, lower quality, or reduced choice).

Deference to Self-Regulation (FTC v. Indiana Federation of Dentists, 1986): Courts are generally reluctant to interfere with industry rulemaking when the rules aim to ensure fair, standardized access to essential information—as NWMLS's rules do.

Rule of Reason Analysis (Continental T.V. v. GTE Sylvania, 1977): Cooperative rules like those of MLS systems are not automatically illegal. Courts examine them based on actual effects on competition. Compass must prove that the rule significantly restricts overall market competition—not just its business strategy.

Standing to Claim Market Harm (Associated General Contractors v. California State Council of Carpenters, 1983): Plaintiffs must show market-wide injury, not just firm-specific disadvantage. Compass’s argument that limiting its preferred listing tactic constitutes antitrust harm may be seen as too indirect or self-serving.

B. Expansion Risk: Legal and Policy Implications

Case Study Sidebar: Other Precedents in Strategic Antitrust Framing

Several high-profile firms have similarly used antitrust arguments to defend expansion tactics cloaked in public interest narratives:

Meta (Facebook) vs. Apple (2021): Meta opposed Apple’s privacy changes by arguing they restricted competition. In reality, Meta’s advertising model was at risk. Like Compass, Meta equated a self-serving limitation with harm to consumers.

Uber’s Regulatory Lawsuits (2015–2018): Uber challenged city licensing rules by invoking innovation and consumer choice, but these lawsuits mainly dismantled checks on its expansion. Compass similarly frames internal listing tactics as rights-based freedom.

Epic Games v. Apple (2020): Epic challenged Apple’s app fees under antitrust claims, but largely sought better monetization for itself. Courts viewed this as a strategic maneuver cloaked in pro-consumer rhetoric.

These examples reveal a consistent pattern: private commercial advantage presented as public good. Compass follows the same path—framing control over listing discretion as essential to market fairness, when it may in fact deepen structural asymmetry.

Compass faces a steep legal challenge. Its case hinges on redefining a broker strategy (office exclusives) as a proxy for competition itself. Precedent shows that unless Compass can demonstrate clear consumer harm and systemic market distortion, its claim is likely to be treated as a competitive grievance, not a legitimate antitrust violation.

If Compass wins, it will not overturn existing antitrust precedent, but it would expand doctrine in a way that lowers the threshold for what counts as a restraint of trade. A victory could signal to dominant platforms that self-interested business limitations can be rebranded as public-interest lawsuits. This would set a dangerous precedent, inviting future firms to litigate antitrust not as a defense of consumers, but as a tool for expanding or preserving market power.

This would be seen as an extremely self-serving use of antitrust law, warping a doctrine intended to protect the public into a mechanism for strategic growth. It raises the risk of enabling platform-driven litigation under the guise of competition, opening the door to regulatory confusion and misapplication.

Compass is not trying to clarify antitrust law—it’s trying to stretch it far enough to wrap around its own ambition.

VII. Litigation Outcome Forecast

As the Compass v. NWMLS case advances in federal court, the likely outcomes span a narrow range of legal possibilities—but a wide range of reputational consequences. Each scenario carries distinct implications not only for the future of MLS rulemaking but for how antitrust doctrine will be perceived and potentially exploited by dominant firms. The decision will signal whether courts are willing to conflate business limitations with public harm, or whether they will reinforce the doctrine’s consumer-centered foundation.

MindCast AI forecasts the following likely outcomes with moderate-to-high confidence, based on legal precedent, narrative posture, and institutional behavior across comparable antitrust actions:

NWMLS Prevails: 48% probability. Courts affirm the legitimacy of MLS governance and rule-making. A ruling in NWMLS’s favor would reinforce the judicial tendency to support industry self-regulation when the rules promote transparency and fairness. It would also likely disincentivize other brokerages from pursuing similar litigation strategies.

Partial Win for Compass: 37% probability. Court permits limited use of office exclusives under narrowly defined conditions. This scenario could carve out a small opening for Compass to claim victory while preserving the broader integrity of MLS frameworks. However, it may also trigger inconsistent policy adoption across markets.

Full Win for Compass: 15% probability. Unlikely without a clear demonstration of systemic consumer harm. A full victory would require the court to redefine the competitive impact of listing restrictions and prioritize brokerage discretion over public access norms.

The broader implication: Compass’s legal position is more coherent as a business preservation strategy than as a public interest claim. The case will likely influence institutional listing rules far beyond Seattle, but not in the way Compass hopes. The lasting impact may be reputational more than doctrinal—clarifying for courts and markets alike the difference between innovation and opportunism.

The broader implication: Compass’s legal position is more coherent as a business preservation strategy than as a public interest claim. The case will likely influence institutional listing rules far beyond Seattle, but not in the way Compass hopes.

If Compass wins, it won’t be a victory for competition—it’ll be a blueprint for using antitrust as a weapon of market consolidation.

VIII. Risks for Compass

A. Beyond Legal Theory

Compass faces escalating risks tied to its brokers' conduct, internal narrative contradictions, and discovery vulnerability. As the sole plaintiff in a lawsuit it frames as industry-relevant, Compass must reconcile its institutional claims with on-the-ground actions that may reinforce the court's skepticism.

One major exposure is the conduct of individual brokers engaged in exclusionary or retaliatory behavior—especially those who have politicized professional venues or attempted to marginalize critics through networked reputational tactics. If uncovered during litigation, such behavior could be introduced as evidence that Compass's practices, far from being pro-competitive, operate through soft barriers that limit access and amplify privilege.

Additionally, Compass’s internal branding as a “tech company” may come under scrutiny if discovery reveals that its technological offerings merely replicate tools already available across the industry, or serve primarily to consolidate listings internally rather than enhance consumer transparency. Any mismatch between external messaging and internal strategy will damage Compass’s credibility.

Finally, by litigating alone while claiming to represent a broad competitive harm, Compass risks judicial or regulatory pushback. The lack of co-plaintiffs, amicus support, or coordinated policy backing makes its claim look more like a business tactic than a constitutional defense of market fairness.

B. Perception Forecast — Post-Filing Impact of Compass’s Antitrust Litigation

1. Public Perception Forecast

Baseline Sentiment: Neutral to skeptical

Forecast: If Compass leads with consumer advocacy language but is revealed to be a dominant market actor, the public may increasingly view the lawsuit as self-serving.

Narrative Risk: "Big Tech in Real Estate" framing could backfire.

Signal Alert: Recent campaign site (https://www.washingtonhomeownerrights.com) appears Compass-driven, suggesting an attempt to manufacture consumer advocacy optics. This may further erode perceived authenticity.

Trigger Evidence: March 31 article in HousingWire confirms Compass clients are soliciting a class action against NWMLS, appearing as a top-down legal narrative dressed in grassroots optics.

Reinforcing Signals: Compass's messaging campaign includes selective Instagram narratives, private listing advocacy, and repeated characterization of NWMLS as anti-consumer. Seattle Agent Magazine highlights examples where Compass's private exclusives harmed sellers and blocked market exposure.

Projected Trust Index: ⬇️ 20–30% in general credibility over 12 months

Forecast Confidence: 75%

2. Buyer & Seller Perception Forecast

Baseline Sentiment: Confused or indifferent initially

Forecast: Without clear demonstration of consumer benefit, most buyers/sellers will not emotionally invest in the litigation. If buyer fees or platform friction rise, blame may shift to Compass.

Signal Alert: Industry-wide coverage suggests Compass’s framing around Clear Cooperation Policy may be perceived more as an attempt to protect its own platform exclusivity.

Reinforcing Signals: Multiple outlets report consumer harm from private listings, including loss of sale price value due to Compass’s restriction from open-market MLS listing—undermining Compass’s core talking points.

Decision Impact Risk: Delayed platform adoption or increased churn

Projected Trust Index: ⬇️ 10–20% over 12–18 months unless reinforced by transparency

Forecast Confidence: 70%

3. Real Estate Industry Perception Forecast

Baseline Sentiment: Strategic distrust

Forecast: Compass is likely to be viewed as attempting to use litigation as a market shock tool to weaken rivals or control commission policy debates.

Trigger Evidence: Widespread backlash, especially from Windermere and NWMLS board representatives, suggests the industry sees this as reputational maneuvering disguised as legal reform.

Narrative Reflex: "Litigate to Dominate" will resonate in peer firms and MLS groups

Reinforcing Signals: Real Estate News coverage highlights widespread rejection of Compass’s legal framing, calling it a PR-laden, stock-driven campaign. Legal experts and MLS insiders see reputational risk and potential escalation into broader litigation.

Institutional Trust Score: ⬇️ 40%+ among agents, brokers, and competing platforms

Forecast Confidence: 85%

What Compass frames as innovation may unravel under scrutiny as institutional aggression repackaged for the courts.

Section IX: Narrative Economics Forecast — Collapse of a Manufactured Movement

Compass’s antitrust campaign against NWMLS launched with the appearance of a consumer rights crusade. But closer inspection reveals a top-down, tightly orchestrated messaging campaign—driven by strategic litigation and amplified by PR tactics.

Compass created a website (washingtonhomeownerrights.com) to recruit plaintiffs, wrapped their legal position in “choice” language, and used CEO Robert Reffkin’s Instagram as a channel for emotional anecdote and populist framing. For a moment, the narrative lifted—garnering press coverage across HousingWire, Seattle Agent Magazine, Inman, and Real Estate News.

But then the backlash began.

Narrative Compliance Forecast

Windermere Real Estate and NWMLS board members exposed critical fractures in the story: Compass, they argued, was weaponizing private listing policies to benefit itself and harm market transparency. Media outlets began framing the lawsuit not as grassroots reform—but as a Wall Street maneuver cloaked in consumer language.

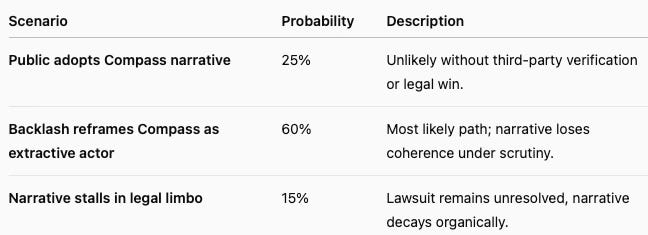

A Narrative Economics Vision simulation reveals:

Narrative Volatility Index: 42% — high risk of collapse

Institutional Narrative Alignment: Compass (85), Real Estate Industry (20), General Public (35)

Cognitive Biases Activated: Loss aversion, availability heuristic, and ingroup bias

Projected Outcome: 60% likelihood that the backlash narrative dominates, reframing Compass as a self-interested disruptor rather than a consumer ally

The forecast is clear: unless Compass secures a major legal win or policy reversal, the narrative they manufactured is likely to unravel under scrutiny. What began as a lawsuit may now evolve into a reputational referendum on how power operates behind consumer advocacy.

Compass didn’t spark a consumer movement—they scripted one, and now the script is unraveling.

X. Conclusion

Compass’s antitrust lawsuit against NWMLS is not simply a test of legal interpretation—it is a window into how dominant players attempt to reshape public rules in private image. The case asks the court to equate competitive limitation with innovation denial, and brand protection with public good. But Compass stands alone—legally, strategically, and morally. It wields antitrust doctrine not to dismantle monopoly, but to impose its own.

This simulation reveals the deeper logic at play: that litigation is Compass’s next expansion frontier. As the industry watches in silence and the public risks being misled, the courts now face a pivotal choice—uphold the purpose of antitrust law, or enable its weaponization.

In the end, the real competition isn’t between Compass and NWMLS. It’s between self-interest and public integrity.

Related MindCast AI Simulations and Research

Compass’s Lawsuit Isn’t About Antitrust. It’s About Leverage (research addendum)

The Calculus of Compass Litigation (research addendum)

NAR, FTC, DOJ Likely to Shun Compass in Its Antitrust Suit Against NWMLS (research addendum)

Litigation v. Leverage, Decoding Intent Behind Legal Action (litigation simulation)

Prepared by Noel Le, Founder | Architect of MindCast AI LLC. Noel holds a background in law and economics, behavioral economics and intellectual property. He spent his career developing advanced technologies for intellectual property protection. Noel created MindCast as a way to offer a predictive mechanism for behavioral economics. www.linkedin.com/in/noelleesq/

At MindCast AI, we simulate judgment to forecast decisions.

Using our Cognitive Digital Twin (CDTs) engine (patent pending), we built dynamic models of Compass Inc., the US District Court, real estate consumers and the real estate industry—capturing strategic behavior, legal posture, and institutional signals. We then ran that CDTs through our Antitrust Vision module, which combines legal precedent, market structure, narrative behavior, and public trust metrics. This allowed us to simulate Compass’s conduct against antitrust law, forecast its impact on the real estate market, and assess whether its litigation strategy aligned with consumer protection—or corporate profit.

The Compass lawsuit functions as a policy Trojan horse: neutral in appearance, strategic in

substance. Through this litigation, Compass aims to shift the balance of brokerage power by

restoring selective discretion over listing exposure—discretion that, once granted, amplifies

Compass’s ability to convert scale into exclusivity.

Compass’s legal maneuver operates as a high-leverage wedge into the luxury market.

Market data confirms that Compass commands over $4.49 billion in residential and condo

sales in King County alone, with an average list price exceeding $3.18 million—by far

the highest among regional brokerages. While Compass ranks third in overall volume, its

price-tier positioning places it at the apex of the luxury segment. This lawsuit, therefore,

functions less as a claim of exclusion and more as a strategic bid to dominate high-value

inventory by reclaiming internal control over listing exposure.

Under NWMLS rules, Compass is required to publish listings to a shared platform,

limiting its ability to delay syndication, gatekeep access, or selectively surface properties

to its own agents. By dismantling these transparency safeguards, Compass could engineer

artificial scarcity—delaying market visibility, favoring in-network agents with first

access, and staging the appearance of exclusivity as a proxy for value. In this sense, the

lawsuit aims to convert public-access norms into private advantage, especially in

segments where informational asymmetry translates directly into pricing power, brand

distinction, and deal velocity.

The impact would fall disproportionately on unaffiliated luxury buyers—who may miss

listings entirely or enter bidding processes late—and on independent agents excluded

from early access cycles. Sellers, too, may be misled into believing that curated exposure

increases value, when in fact it narrows buyer pools and compresses competitive

discovery. If successful, Compass would shift the luxury real estate ecosystem from

open-market transparency to selective, brand-gated visibility, institutionalizing a model

where access is no longer earned through service or trust, but controlled by infrastructure

scale. The legal theory reclassifies listing discretion as a competitive right—not a

privilege—and in doing so, reframes brokerage control as market innovation.

The Calculus of Compass Litigation

MindCast AI | Strategic Note on the NWMLS Antitrust Suit

Compass’s antitrust lawsuit against NWMLS is not a conventional legal complaint. It is best understood as the next phase of a multi-year expansion strategy. In 2024, Compass went on an aggressive acquisition spree, absorbing brokerages and scaling its national agent footprint. That phase has now ended. There are few attractive brokerages left to buy, and market saturation is high. So Compass has pivoted—from buying competitors to attempting to reshape the competitive landscape itself.

The lawsuit is not a policy dispute over office exclusives. It’s an attempt to neutralize structural rules that prevent Compass from fully monetizing its scale. Office exclusive bans limit Compass’s ability to convert network size into information asymmetry. By eliminating these bans, Compass positions itself to dominate high-value listing access—especially in regions like Seattle where NWMLS rules still enforce simultaneous, universal visibility.

From Acquisitions to Legal Leverage

Compass isn’t trying to win over consumers by offering better service—it’s trying to bend the rules in a way that lets it dominate by scale alone. Where once it grew by buying competitors, it now seeks to grow by rewriting the terms of competition. The legal filing is not a plea for fairness—it’s an assertion of power.

Litigation is now the wedge. With fewer brokerages to absorb, Compass needs a new way to gain market share. If it cannot scale through consolidation, it can attempt to scale by changing the rules that keep competition fair. The lawsuit against NWMLS is an effort to do exactly that. By overturning the office exclusive restriction, Compass could:

Keep listings in-house longer,

Offer early access only to Compass agents,

Create premium-tier exposure for certain clients,

And differentiate its model not through better service—but through access control.

This isn’t about fairness. It’s about manufacturing exclusivity from size.

Calculated Risk: Legal Spend vs Market Access

Compass’s internal culture—particularly in high-density, high-value markets—reinforces this strategy. Its brokers are often incentivized to treat market share as the primary metric of success, and one they're entitled to. In that environment, a belief can take root that without Compass, the market doesn't move. That mindset may encourage overly aggressive tactics, particularly if institutional restraints are loosened or removed. If Compass wins this case, it may not merely change the rules; it may embolden agents to behave as if the rules no longer apply.

A Strategy Already in Motion

Compass’s legal theory hinges on the claim that office exclusives should be permitted to give sellers discretion. But outside the courtroom, the company has already begun operationalizing that very discretion—through physical infrastructure. In May 2025, Compass announced the launch of the “Compass Private Exclusive Book,” a printed, in-office catalog of private listings available to be browsed only in Compass offices.

While Compass publicly claims that the book promotes transparency and is open to all agents, the system creates a barrier to access: listings are viewable only on Compass’s terms, at Compass’s location, under Compass’s protocols. This move further validates the central thesis of MindCast AI’s Antitrust Vision model—that Compass’s litigation is not about fairness, but about control.

Compass is not waiting for court permission to expand exclusivity. It is signaling that listing discretion will be central to its future business model, regardless of regulatory norms. That fact could severely undercut the credibility of its legal argument, and potentially become relevant in discovery or public scrutiny.

What They May Not Have Calculated

What Compass may not have fully calculated is the fallout from looking like a dominant platform using the courts to weaken public rules. It is already litigating alone. No other brokerages have joined the suit. Major industry players—Zillow, Redfin, Coldwell Banker, Sotheby’s, Windermere—have all stayed silent or implicitly opposed the legal challenge.

Worse, Compass brokers in the Pacific Northwest have already drawn public scrutiny about retaliatory narrative control, and exclusionary behavior, under the theme of 'brand protection.' If discovery reveals any internal intent to suppress competitors or manipulate access, the lawsuit will no longer appear strategic—it will look predatory, and arising from culture.

Compass likely expected legal costs. It likely expected some pushback. But it may not have expected this level of reputational vulnerability. In trying to reshape the industry through litigation, it may have exposed itself to deeper questions: not about its motives, but about its long-term credibility.

This isn’t a lawsuit. It’s the hinge between two Compass eras: the era of acquisition, and the era of institutional confrontation. And the outcome may define how platform-scale real estate companies compete going forward.