MCAI Market Vision: Arbitration in the Energy Age, Who Controls the Future of Oil?

The Chevron-Exxon-Hess Dispute, Consumer Risk, and the Strategic Stakes of Trust

I. Introduction — A Hidden Battle Over Oil, Contracts, and Control

The arbitration between Exxon and Chevron over Hess's Guyana stake is more than a legal skirmish between oil giants—it's a litmus test for how energy power is structured, regulated, and ultimately felt by the public. At the heart of the conflict is a question of control disguised as a technical dispute: does a corporate acquisition sidestep contractual obligations meant to ensure fair participation in vital natural resources? The answer will set a precedent not just for mergers, but for the governance of energy itself in a time when reliability, price stability, and public accountability are under growing strain. Consumers, though absent from the arbitration room, are the most impacted stakeholder group in this unfolding drama.

Chevron’s $53 billion acquisition of Hess hinges on control of Guyana’s rapidly expanding offshore oil production—especially the prized Stabroek block. The company frames its acquisition as a corporate merger, arguing it should not trigger the consortium’s right of first refusal (ROFR). This position allows Chevron to sidestep potential roadblocks posed by Exxon and CNOOC, current consortium members. From a production standpoint, Chevron’s deal could increase output and stabilize global supply. But it raises structural questions about whether acquisition design can be used to circumvent shared governance.

Exxon challenges this framing, asserting that the ROFR should apply regardless of whether the transaction is structured as a corporate deal or asset sale. The company argues that the practical effect—a transfer of control over a key asset—triggers their pre-emption rights. Exxon’s stance reinforces contractual predictability and sets a protective precedent for joint venture stakeholders across industries. At the same time, the enforcement of this logic may slow development and delay oil reaching global markets. This introduces friction between legal consistency and market responsiveness.

Insight: This arbitration is not just about who wins a contract, but about whether institutional design can adapt to power without eroding public trust in the rules of governance.

II. Scenario Analysis — Outcomes and Implications

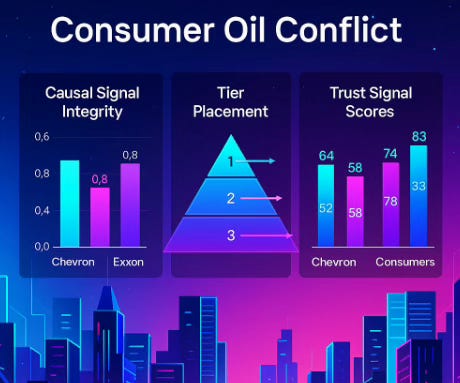

Consumers, meanwhile, are structurally sidelined yet highly vulnerable. Their exposure to the outcome manifests in oil prices, supply chain delays, and national energy security strategies. The MAP CDT Flow for consumers reveals Tier 3–4 placement: limited agency, fragmented visibility, and downstream dependence on opaque institutional decisions. Their Causal Signal Integrity score is low—indicating poor information access and weak leverage. Still, their long-term interests hinge on two things: speed of development and preservation of trust in institutional contracts.

If Chevron prevails outright, the result could accelerate production and support global supply stability. Consumers benefit from faster development of Guyana’s oil fields and competitive pressure between energy giants. However, the method of victory—bypassing ROFR through corporate structuring—may erode long-term trust in joint venture governance, setting a dangerous precedent for future deals. The gain in supply velocity may come at the cost of diminished transparency and weakened oversight.

If Exxon prevails and the ROFR is enforced, the legal integrity of joint ventures is strengthened. This outcome supports rule-based energy governance and affirms contractual obligations, reducing uncertainty in future partnerships. But it also risks delaying production and introducing friction into an already strained global energy market. Consumers could face higher prices and longer supply lags as a result.

A hybrid resolution—where arbitration affirms the ROFR’s legal standing but allows Chevron to proceed under modified terms—offers the best of both. Production remains on track, while legal clarity is preserved. Investors remain confident, and consortium integrity is not compromised. This outcome supports both operational speed and systemic trust, aligning closely with the long-term interests of consumers.

Insight: The outcome with the greatest public benefit is not determined by speed or legality alone, but by how well it aligns structural incentives with consumer security over time.

III. Optimal Path Forward — Structuring Trust Through Foresight

MindCast AI forecasts this hybrid resolution as the most foresight-aligned outcome. MCAI’s MAP CDT Flow simulations show that this approach preserves both economic velocity and legal accountability. Chevron operates in Tier 2–3, strong on investor foresight but legally vulnerable. Exxon holds Tier 2 positioning—strong procedural coherence but with potential reputational friction. Consumers remain underrepresented but emerge as the group most aligned with systemic equilibrium. MCAI activates Trust Vision, Legal Vision, and Causation Vision simultaneously to project the trust delta under each outcome. It finds that structural fairness—not speed or control alone—produces the highest trust signal across all tiers.

To institutional actors, this isn’t just an arbitration—it’s an opportunity to codify a new layer of global governance in resource development. Regulatory bodies can use the insights surfaced by MCAI to clarify merger rules, enforce accountability, and safeguard consumer interests in high-stakes zones like Guyana. Investors can better price reputational risk and forecast governance friction, reducing their own exposure to opaque decisions. Civil society can translate simulations into citizen advocacy, bridging the gap between strategic decisions and public consequences.

MCAI enables regulators, investors, and civil society to see the invisible: how arbitration decisions cascade through systems the public depends on but cannot influence. By simulating legal coherence, causal integrity, and public impact, MCAI doesn’t just model outcomes—it models evolution. In this conflict, victory is not in Chevron’s deal or Exxon’s veto, but in the emergence of an energy architecture where trust, foresight, and public alignment can coexist.

Insight: Structural fairness emerges when decision-making power is paired with systems that can simulate, test, and reinforce public-aligned foresight—before damage becomes legacy.

IV. Conclusion: Structuring Energy Futures in the Public Interest

The Chevron-Exxon arbitration represents more than a multibillion-dollar oil dispute—it is a turning point in how institutional contracts, corporate strategy, and public well-being intersect. Consumers may not hold seats at the table, but their stakes are highest. The outcome will shape not just who extracts oil in Guyana, but how trust is earned, distributed, and operationalized across global systems. A hybrid resolution that blends legal integrity with production urgency stands as the clearest path toward equity and efficiency. With tools like MindCast AI, society can move beyond reaction into structural foresight—ensuring that future energy architectures evolve toward transparency, coherence, and public trust.

Prepared by Noel Le, Founder | Architect of MindCast AI LLC. Noel holds a background in law and economics. noel@mindcast-ai.com, www.linkedin.com/in/noelleesq