MCAI AI Lex Vision: The Legal Trust Paradox, Compass's Antitrust Lawsuit Risks Its Own Exposure

What Rumble Got Right—and Compass Got Dangerously Wrong in the Battle Over Market Power and Public Trust

Introduction

When a company decides to challenge a dominant player under antitrust law, how the case is framed can determine whether it garners public support, regulatory traction, or courtroom success. Two examples, Rumble v. Google and Compass v. NWMLS, provide a stark contrast in narrative structure, legal grounding, and public trust positioning. Each reveals what a well-constructed antitrust theory looks like—and what pitfalls to avoid.

Rumble v. Google: A Coherent Antitrust Narrative

Rumble’s lawsuit against Google illustrates a more coherent approach. Though Rumble is a competitor-plaintiff, it thoughtfully links its exclusion from fair search visibility to consumer harm. The case alleges that Google manipulates search results to favor its own platform, YouTube, even when users explicitly search for Rumble content. This, Rumble argues, diminishes consumer choice, reduces innovation, and locks users into the Android–YouTube ecosystem through preinstalled apps. While the harm to Rumble as a business is central, the company frames this harm as a signal of broader market failure, aligning its legal strategy with longstanding antitrust principles like foreclosure theory and consumer choice doctrine. It draws support from recognized precedents, such as the Microsoft and Google Shopping cases, reinforcing its structural argument. Rumble v. Google, Case No. 4:21-cv-00229-HSG, N.D. Cal. (2021)

Compass v. Northwest MLS: A Case Undone by Contradiction

By contrast, Compass’s lawsuit against Northwest MLS struggles with internal coherence. On its face, the case alleges that NWMLS exerts undue control over real estate listing structures in ways that hurt consumers. However, Compass’s own behavior—such as its embrace of exclusive off-MLS listings, opaque dual agency practices, and aggressive commission strategies—undermines the credibility of its claims. Rather than standing apart from the harm it describes, Compass often appears to perpetuate it. MCAI simulations highlight that the firm may be accelerating, not remedying, consumer confusion and market distortion. Compass v. Northwest MLS, Case No. 2:23-cv-01834, W.D. Wash. (2023)

Compass also fails to construct a consistent causal model. While it claims NWMLS restricts competition, it offers little evidence of direct or indirect consumer injury beyond its strategic grievances. Its framing feels opportunistic and poorly aligned with antitrust norms, leading to skepticism from both the public and regulators. In contrast to Rumble’s ecosystem critique, Compass’s case appears self-serving, and this inconsistency weakens its moral and legal standing.

Legal Weaponization: Compass in Context

This is not the first time the legal system has been weaponized by a powerful actor attempting to obscure its own market behavior. Similar patterns emerge in other high-profile cases where the legal system was used as a weapon rather than a shield:

Peter Thiel and the Gawker Lawsuit: Billionaire Peter Thiel covertly funded Hulk Hogan's invasion-of-privacy lawsuit against Gawker Media after the site had previously outed him. Though the claim itself had legal merit, Thiel's involvement was motivated by personal vendetta and aimed at dismantling a media organization. It succeeded: Gawker was bankrupted, raising questions about how financial power can silence critical journalism through calculated legal action.

ExxonMobil vs. State Attorneys General: In response to investigations into whether ExxonMobil misled the public about climate change, the company filed lawsuits against the attorneys general of Massachusetts and New York. These lawsuits sought to discredit and halt the inquiries, framing them as politically motivated harassment. Critics viewed these legal tactics as attempts to chill legitimate regulatory scrutiny and delay public accountability.

Donald Trump’s Lawsuits Against Media Outlets and Critics: Former President Trump has repeatedly filed defamation lawsuits against media organizations, journalists, and political opponents. Many of these cases were later dismissed or withdrawn, but they often served to intimidate, exhaust resources, and influence public perception. The strategy highlights how litigation can be leveraged to control narratives rather than resolve authentic legal grievances.

Compass's strategy fits this archetype. Rather than offering a clean antitrust theory, it cloaks its own market distortions in the guise of consumer protection—an inversion that can damage not just its credibility but the legitimacy of antitrust enforcement itself.

Breaking the Rules of Trust in Real Estate

In abusing the legal system to target NWMLS while engaging in similarly exclusionary practices, Compass violates the foundational trust principles of real estate. The industry depends on transparency, access, and fiduciary duty—values Compass actively erodes through off-market listings, conflicted dual agency, and platform-driven opacity. By suing NWMLS under the banner of consumer harm, while structurally participating in the very behaviors it condemns, Compass exposes itself as a bad-faith actor whose legal strategy mirrors its market strategy: extractive, confusing, and fundamentally misaligned with public interest.

Opening the Door to Its Own Antitrust Exposure

This risk is underscored by foundational antitrust case law. In FTC v. Indiana Federation of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447 (1986), the Supreme Court found that withholding information from consumers can constitute an unreasonable restraint of trade—a principle relevant to Compass’s practice of restricting listing access through off-market exclusivity. In Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Services, Inc., 504 U.S. 451 (1992), the Court emphasized that leveraging power in one market to distort another can give rise to liability—a concept mirrored in Compass's bundling of tech platforms, agent services, and listing control.

Economically, the concerns are not new. The DOJ's Statement of Interest in Moehrl v. NAR, Case No. 1:19-cv-01610 (N.D. Ill. 2020), criticized practices that reduce commission transparency and distort broker incentives—precisely the kind of opaque dynamics Compass promotes under the guise of innovation. Legal scholars have also flagged the risks of bundling and dual agency in real estate. For instance, Einer Elhauge’s seminal article, “Tying, Bundled Discounts, and Loyalty Discounts: What’s the Rule?” 50 Antitrust Bulletin 1 (2005), outlines how platform-driven integration strategies can stifle competition.

Finally, the Yale Journal on Regulation’s 2021 bulletin on real estate platforms warned that firms straddling technology and brokerage roles could subvert fiduciary norms by embedding conflicting incentives into their ecosystems. These citations collectively form a case for why Compass's litigation posturing may not only be legally unpersuasive—it may be dangerously self-incriminating.

More ironically, Compass’s lawsuit, if successful, could set a precedent that exposes its own business model to future antitrust scrutiny. By challenging the rules of listing access and market control, Compass invites regulators to ask whether its own consolidation tactics, exclusive inventory practices, and agent poaching schemes create precisely the anticompetitive risks it claims to oppose. Should Compass win relief or concessions, it could be hoisted by its own legal logic—paving the way for DOJ or state-level investigations that flip the same theories Compass deployed against NWMLS back onto itself.

MCAI Evaluation and Final Takeaways

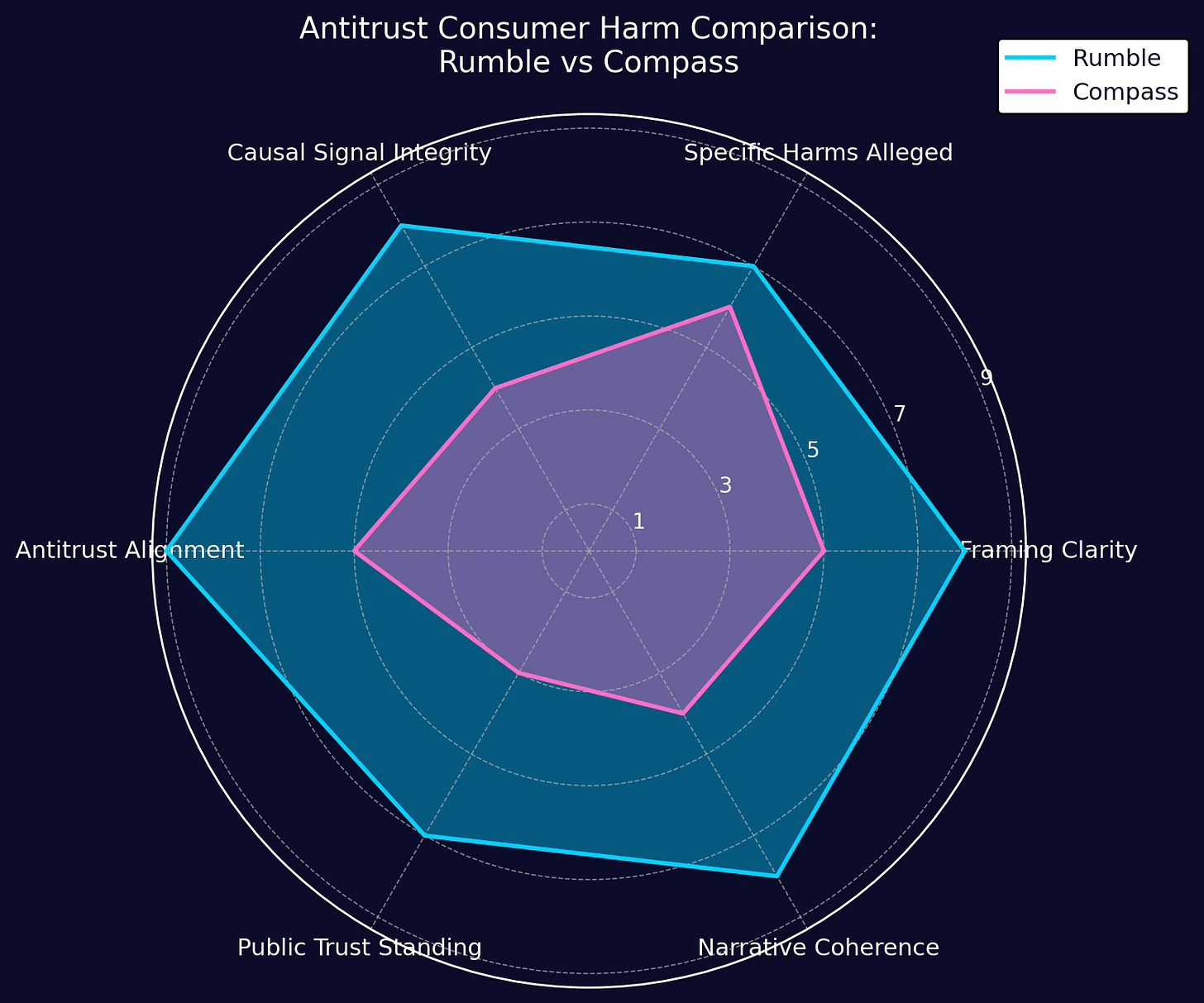

Seen through MCAI’s lens, the difference in quality between the two cases can be mapped across several dimensions: narrative coherence, public trust alignment, and causal signal integrity. Rumble scores high on all three—its story is clear, its consumer harm theory is plausible, and its legal framing aligns with institutional norms. Compass falls short, confusing its market strategy with principled advocacy, and eroding its own argument in the process.

In short, crafting an effective antitrust lawsuit requires more than alleging unfairness. It requires structural clarity, foresight, and moral coherence. Rumble’s lawsuit succeeds because it embeds its competitive injury within a wider system critique. Compass’s, on the other hand, reminds us what happens when a plaintiff tries to be both disruptor and monopolist. The result is a diluted message, reduced trust, and a missed opportunity for meaningful reform.

Prepared by Noel Le, Founder | Architect, MindCast AI LLC. Noel holds a background in law and economics. noel@mindcast-ai.com