MCAI National Innovation Vision: USPTO Inter Partes Review Governance and Innovation

How Discretionary IPR Denials Turn Patent Procedure into an Innovation Tax

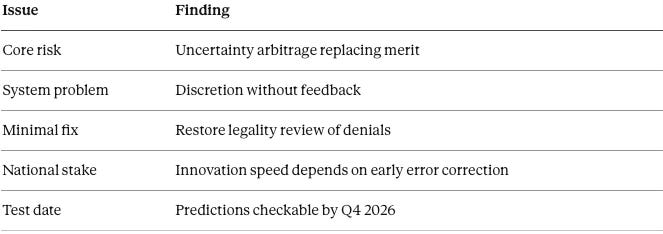

Executive Summary

The USPTO’s current approach to inter partes review has become a live governance dispute with material consequences for innovation and capital allocation. Congress created IPR in 2011 to provide a fast, expert validity check that removes patents that should never have issued. Since March 2025, Bloomberg reporting describes discretionary denials exceeding 60%, often without merits review. Recent Federal Circuit doctrine interpreting §314(d)’s “final and nonappealable” language has largely insulated these denials from correction.

Patent uncertainty operates as an innovation tax. When invalid patents cannot be tested early, startups and operating companies spend more on defense, investors discount valuations, and capital flows toward firms that can carry litigation tails rather than firms with the best technology. CDT metrics indicate a 46% decline in national innovation throughput coherence under the current regime.

The distributional effects are predictable. Patent assertion entities and large incumbents with deep portfolios benefit most; startups, small operating companies, and independent AI infrastructure builders bear the cost.

The forecast is falsifiable. If current policies persist through 2026, the model predicts a 20–30% increase in AI-adjacent assertion filings concentrated in EDTX/WDTX, higher early settlement values, accelerated vertical integration, and a measurable decline in independent deep-tech venture formation. If these patterns do not materialize by Q4 2026, the model requires revision.

The minimal repair is narrow: restore legality-based review of institution denials while preserving nonappealable grants. The goal is not fewer patents or more patents; the goal is early error correction instead of discretionary opacity.

I. What Is Inter Partes Review?

In 2011, Congress added a new tool to the patent system: inter partes review, or IPR. The idea was straightforward. Patents get granted through a one-sided process—just the applicant and an examiner, no one pushing back. Mistakes happen. Some patents cover ideas that were already public or too obvious to deserve protection. Before IPR, the only way to challenge those patents was federal court, which meant years of litigation and millions in legal fees. IPR created a faster, cheaper alternative: a second look by technically trained Patent Office judges who could cancel bad patents in about 18 months.

Why the Patent Office Needs a Second Look

Patent examiners work under real constraints. They have limited time per application, access only to certain databases, and no adversary pointing out weaknesses. The system is designed to be efficient, not exhaustive. As a result, some patents issue that probably shouldn’t. Maybe the invention was already described in an obscure technical paper. Maybe it was obvious to anyone working in the field. These errors aren’t scandalous—they’re inevitable in a high-volume administrative process.

The problem is what happens next. A weak patent can still be enforced. The holder can sue competitors, demand licensing fees, or threaten litigation. Before IPR, defendants had one option: fight it out in federal court, where patent cases routinely cost $2–5 million and take three to five years. Many companies paid settlements instead—not because the patent was valid, but because proving otherwise cost more than giving in.

How IPR Changed the Calculation

IPR shifted the economics. A company facing a patent lawsuit (or expecting one) can now petition the Patent Office to review the patent’s validity. Administrative judges with technical backgrounds—many are former patent examiners or engineers—examine whether the patent should have issued in the first place. The process is faster (typically 12–18 months), cheaper (usually under $500,000), and decided by specialists rather than generalist judges or juries.

IPR doesn’t replace courts entirely. Courts still handle infringement questions—whether someone actually copied the patented invention. But IPR handles the threshold question: should this patent exist at all? When IPR works, weak patents get filtered out early, strong patents get validated, and both sides save the cost of fighting over rights that shouldn’t have been granted.

IPR exists because patent examination can’t catch every error, and federal litigation is too slow and expensive to serve as the primary correction mechanism. Congress designed IPR as a pressure-relief valve—a way to remove invalid patents before they clog the courts and extract undeserved payments. When that valve closes, the pressure doesn’t disappear. Disputes migrate to slower, more expensive forums, and weak patents persist longer.

Insight: IPR works like a quality-control checkpoint—catch the defects early, before they cause expensive problems downstream.

II. Why Error Correction Matters for Innovation

Patent validity sounds like a legal technicality. It’s not. The speed at which the system can sort valid patents from invalid ones shapes investment decisions, product timelines, and which companies survive. When bad patents can’t be challenged efficiently, the effects ripple outward—into venture funding, corporate R&D, and market structure.

The Uncertainty Problem

A valid patent provides clarity. Companies know what’s protected and can plan around it—license the technology, design something different, or wait for the patent to expire. An invalid patent creates the opposite: ambiguity that no one can resolve cheaply. The patent holder can still send demand letters, file lawsuits, and negotiate settlements. The target has to decide whether to pay or fight, without knowing whether the patent would actually hold up.

This ambiguity favors the patent holder. Litigation is expensive, and most companies—especially smaller ones—can’t afford to spend $3 million proving a patent shouldn’t exist. So they settle. They pay licensing fees for rights that may be worthless. They avoid product features that might trigger claims. The patent’s validity never gets tested because testing costs more than conceding.

Why Speed Matters

The damage from uncertainty depends heavily on time. Consider a startup raising its Series A. If a competitor’s patent can be reviewed and resolved in 18 months, investors can factor that into their risk assessment. The company has a path forward. But if the same challenge takes four or five years in federal court, the startup may run out of runway before getting an answer. The patent holder doesn’t need to win—just to outlast the challenger.

This dynamic is especially acute in fast-moving sectors. AI capabilities shift quarterly. A three-year patent dispute might outlast the product generation it’s blocking. The company that should have built the next version is instead stuck in legal limbo, burning cash on lawyers instead of engineers.

The Cumulative Tax

When you add up these effects—settlements paid, products delayed, features avoided, investments deferred—they function like a tax on productive activity. The tax doesn’t require any particular bad actor. It emerges from a system where bad patents can’t be cleared efficiently. Every company adjusts its behavior to account for legal risk it can’t resolve, and those adjustments compound across the economy.

Patent uncertainty isn’t abstract—it redirects resources from building to defending, delays deployment, and skews capital toward companies that can absorb legal risk rather than companies with the best technology. The speed of resolution determines whether uncertainty stays a manageable cost or becomes a structural barrier. Slow systems transfer value from creators to those who can wait.

Insight: How long uncertainty lasts matters more than the legal standard for validity—duration determines the toll.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on patent system and national innovation policy foresight simulations.

This foresight simulation builds on prior MindCast AI research examining how patent institutions shape coordination, leverage, and innovation outcomes across technology cycles. Chicago Accelerated Patents establishes the core framework used here, applying modernized Chicago School law-and-economics to show how timing and transaction costs convert patents into coordination infrastructure or arbitrage tools. Quantum Patents extends that framework to environments of extreme uncertainty, modeling how unresolved validity places patents in probabilistic states that reward delay rather than merit. Patent Litigation as a Coordination Game reframes litigation behavior as a strategic equilibrium problem, predicting how parties re-optimize when early validity screening collapses. AI and Intellectual Property analyzes why AI’s layered technical architecture magnifies the cost of patent uncertainty, making early error correction more critical than in prior technology waves. Carrot-and-Stick Damages explains how remedies interact with validity uncertainty to amplify settlement leverage when weak patents survive long enough to extract value. Finally, Predictive Patent Damages provides the timing-based damages model used in this analysis, showing why settlement behavior tracks uncertainty duration rather than doctrinal strength.

III. What Changed Recently

In October 2025, Mark Lemley published an analysis in Bloomberg Law arguing that recent Patent Office restrictions on inter partes review violate the America Invents Act’s statutory design. This foresight simulation treats that dispute as an institutional inflection point and models the downstream innovation, capital, and AI consequences rather than re-litigating the legal question. The article landed in the middle of an ongoing controversy: the Patent Office has made it significantly harder to use IPR, and the changes have largely escaped judicial review.

The New Gatekeeping

Since March 2025, the Patent Office has been rejecting IPR petitions before anyone examines whether the challenged patent is actually valid. Acting Director Coke Morgan Stewart introduced a “settled expectations” factor—essentially a presumption that patents more than six years old shouldn’t face review, because their owners have come to rely on them. Whether the patent should have been granted in the first place doesn’t enter the analysis.

Director John Squires then consolidated these screening decisions in his own office, rather than leaving them to the expert judges Congress empowered to handle IPR. He also began issuing orders structured in ways that make them difficult to appeal. According to Bloomberg reporting, discretionary denials have exceeded 60% since March, with many petitions rejected before anyone looks at the merits.

Why Courts Aren’t Stepping In

The America Invents Act says that decisions about whether to institute IPR are “final and nonappealable.” Congress meant to prevent endless litigation over preliminary rulings. But the Federal Circuit has interpreted this language broadly, treating even decisions based on factors Congress never authorized as essentially immune from review. The result: the Patent Office can apply new screening criteria, and challengers have no practical way to object.

The Practical Effect

Taken together, these changes have transformed IPR from a validity-review mechanism into a gatekeeping function that leadership can restrict at will. Weak patents that previously would have faced expert scrutiny now have a better chance of surviving long enough to be leveraged in litigation or licensing negotiations. The checkpoint Congress designed is no longer reliably open. The Patent Office has sharply curtailed access to IPR through a combination of new discretionary factors, centralized decision-making, and order structures that limit appeals. Courts have largely declined to intervene, interpreting statutory language in ways that insulate these changes from review. The institution designed to screen patent quality now operates more like a gate that can be closed.

Insight: Administrative discretion, exercised without judicial check, has converted IPR from a right into a permission.

IV. How to Think About This: The Economic Framework

Policy arguments often stay abstract—”innovation” versus “patent rights,” with both sides claiming the moral high ground. MindCast AI uses an economic framework grounded in decades of research to make concrete predictions about what happens when legal institutions change. The framework doesn’t take sides on whether patents are good or bad. It asks: what does this system reward, and who adapts?

Three Ideas That Predict Institutional Behavior

Three insights from University of Chicago economists help explain what happens when IPR access shrinks:

Transaction costs matter (Ronald Coase). Coase won the Nobel Prize for showing that legal rules shape how expensive it is to make deals. When it’s cheap to figure out who owns what, markets work smoothly. When it’s expensive, resources flow to whoever can navigate the friction—not necessarily whoever creates the most value. IPR was a transaction-cost reducer: it provided a fast, cheap way to determine whether a patent was valid. Closing that option makes the whole system more expensive to navigate.

People respond to incentives (Gary Becker). Becker, another Nobel laureate, showed that people adjust their behavior based on what the system rewards—even when the rewards come from system failures. If weak patents become harder to challenge, patent holders rationally become more aggressive. Defendants rationally settle more often. Assertion-focused business models become more attractive. None of this requires villainy; it’s just optimization.

Institutions need feedback to learn (Richard Posner). Courts and agencies improve when they can see the results of their decisions and adjust. When feedback loops break—when decisions can’t be reviewed or corrected—institutions drift. Errors persist. Policies that don’t work become entrenched because no one can point out the problem.

Why Time Is the Key Variable

Traditional law-and-economics analysis often treats legal rules as static. MindCast AI’s framework adds a critical factor: speed. In fast-moving technology markets, a legal right that takes five years to resolve is fundamentally different from one that resolves in 18 months. The question isn’t just “what does the law say?” but “how quickly can the system tell us?”

When early screening mechanisms like IPR are constrained, the framework predicts three effects: coordination costs rise (because no one knows which patents are real), exploitation incentives increase (because weak patents become more profitable), and institutional learning degrades (because the feedback loop is cut). The economic framework provides a way to move from abstract debate to testable predictions. It identifies transaction cost increases, rational exploitation of weak enforcement, and institutional learning failures as likely consequences of current IPR policy. The predictions aren’t ideological—they follow from how people and institutions respond to incentives.

Insight: The policy question isn’t whether the Patent Office should have discretion—it’s whether that discretion operates in a system that can identify and correct mistakes.

V. The Simulation: What the Numbers Show

Frameworks are useful, but they can justify almost anything if you’re creative enough. The value of quantitative modeling is that it forces specificity—and specificity can be checked. MindCast AI ran simulations across five different policy scenarios to see how the patent system behaves under each. The numbers that follow aren’t claims of precision; they’re structured comparisons that let us see how much things change depending on which path we’re on.

What We Modeled

We built computational models—what we call Cognitive Digital Twins—of the key institutions and actors in the patent system: the Patent Office, the courts, companies of various sizes, investors, and patent assertion entities. Then we simulated how each would behave across four trajectories (with the fourth forking into two possible futures):

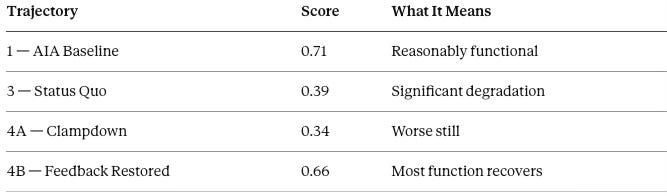

The metrics that follow are normalized scores on a 0–1 scale. What matters isn’t the absolute number—it’s the relative shift between scenarios.

Finding 1: The System Is Coordinating Worse

We measured how well the different parts of the patent system work together—whether companies can figure out what’s protected, whether licensing negotiations reflect actual patent strength, whether the market clears efficiently. We call this System Coordination Integrity.

The drop from 0.71 to 0.39 represents a system where actors increasingly can’t tell which patents are real obstacles and which would fail if tested. Coordination breaks down when no one knows what the rules actually are.

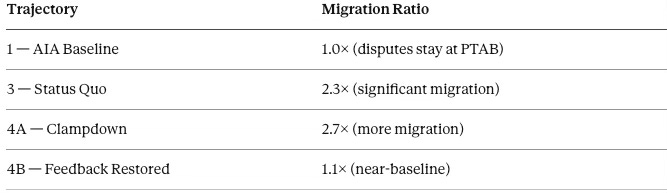

Finding 2: Uncertainty Lasts Much Longer

We measured how long patent validity questions stay unresolved. Under the original design, the average uncertainty resolved in about 12 months. Now it takes closer to three years.

This isn’t just inconvenient—it changes who has leverage. A patent holder who can drag things out for three years has a very different negotiating position than one facing an 18-month IPR.

Finding 3: Disputes Are Moving to Expensive Venues

When IPR isn’t available, disputes don’t disappear. They migrate to federal court and the International Trade Commission—forums that are slower, more expensive, and often less technically sophisticated.

A 2.7× migration ratio means patent leverage is increasingly exercised through expensive litigation rather than efficient expert review. Defendants pay more; the underlying validity questions take longer to resolve.

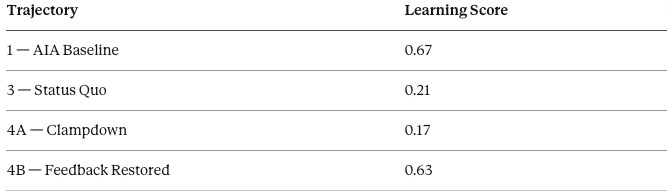

Finding 4: The Institution Stopped Learning

We measured how well the Patent Office adapts based on outcomes. Can it identify policies that aren’t working? Does it adjust?

A 69% drop in institutional learning capacity means the Patent Office is operating without effective feedback. Policies persist whether they work or not, because there’s no mechanism to surface errors.

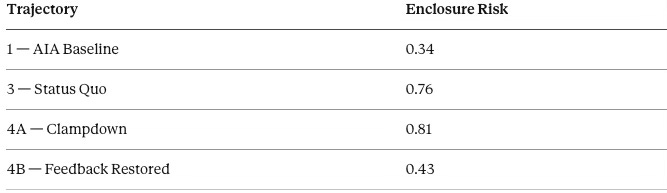

Finding 5: AI Faces Amplified Risk

AI development depends on many technology layers working together—chips, networks, software, data. Patent uncertainty anywhere in that stack creates problems for everything built on top of it.

The risk of the AI stack fragmenting or being enclosed by patent claims has more than doubled. AI’s layered architecture makes it unusually vulnerable to exactly this kind of uncertainty.

The simulation quantifies what the economic framework predicts. Coordination has degraded 45%. Uncertainty lasts nearly three times as long. Disputes have migrated 2.3× toward expensive forums. Institutional learning has dropped 69%. AI enclosure risk has more than doubled. Restoring judicial feedback recovers most of the baseline function without requiring any changes to how the Patent Office handles grants.

The key insight from Trajectory 2 (pre-ambiguity period): the system degrades but does not break as long as feedback remains possible. Once feedback disappears entirely (Trajectory 3), the shift from merit screening to uncertainty arbitrage becomes structural.

Insight: The numbers confirm the framework—blocking early review doesn’t make disputes go away; it makes them slower, more expensive, and harder to resolve.

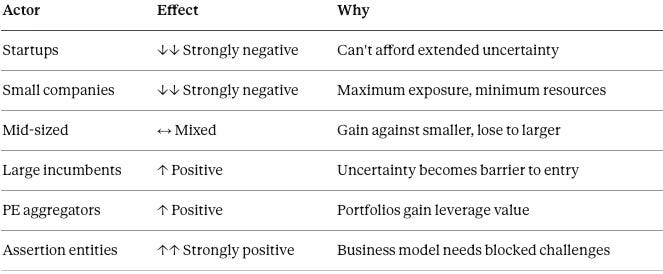

VI. Who Wins and Who Loses

System-level metrics matter, but the real question is: who benefits from these changes, and who gets hurt? The effects aren’t random. They follow predictable patterns based on who can afford to wait out uncertainty and who needs clarity to operate.

Startups: Clear Losers

Startups run on limited time and money. Every dollar spent on legal defense is a dollar not spent on product development. When IPR becomes unreliable, startups face a choice: budget heavily for potential patent fights, or hope they don’t get targeted.

Investors notice. Patent exposure becomes a bigger factor in due diligence, and valuations adjust downward to account for unresolved risk. The companies hit hardest are “deep tech” startups—those building chips, AI infrastructure, or other hardware-adjacent technology where patent density is highest. For these companies, freedom-to-operate analysis used to be manageable. Now it’s unreliable.

The predictable response: early-stage capital shifts toward software plays with lower patent exposure, or toward startups backed by large incumbents who can provide patent protection. Independent ventures in patent-dense sectors face a harder path.

Small Operating Companies: Also Clear Losers

Small companies without patent portfolios of their own are in the worst position. They’re exposed to lawsuits but lack the resources to fight back. They can’t countersue because they don’t have patents to assert. Multi-year federal litigation is out of reach financially. The rational response is early settlement on bad terms, or simply exiting contested product lines.

Large Incumbents: Winners

Big companies with extensive patent portfolios benefit from the uncertainty environment. They can absorb litigation costs that would sink smaller competitors. They can countersue across jurisdictions. They can wait out disputes that would exhaust rivals. Patent uncertainty becomes a competitive moat—potential entrants face legal risk that incumbents can manage but newcomers can’t.

The predictable response: increased market concentration in patent-dense sectors. Large companies use uncertainty strategically to deter entry.

Private Equity: Advantage to Aggregators

For PE-backed roll-ups, patent portfolios become more valuable as offensive and defensive assets. When IPR isn’t available to knock out weak patents, having a portfolio to countersue with is more important. Deal structures adjust: PE sponsors demand broader IP representations, larger escrows, and stronger indemnities.

The predictable response: patent portfolio acquisition becomes a more attractive standalone investment thesis. Aggregating patents and using litigation leverage becomes more profitable.

Patent Assertion Entities: Big Winners

Non-practicing entities—companies that own patents but don’t make products—benefit most directly. Their business model depends on settlement leverage: assert enough patents that defense costs exceed settlement costs, and extract payment. IPR was the main constraint on this model because it gave defendants a fast, cheap way to invalidate weak patents.

With IPR restricted, defendants lose that option. Assertion entities can demand higher settlements, take longer to extract them, and face less risk that their patents will be invalidated along the way.

The predictable response: more patent assertion activity, higher settlement values, expansion of the market for aging patent portfolios, and concentration of litigation in plaintiff-friendly venues like the Eastern District of Texas.

The Pattern

The redistribution is systematic. Actors who can carry uncertainty gain advantage; actors who need clarity to build and operate lose. Capital scale and portfolio depth become more important; innovation and technical merit become less determinative. When a legal system rewards endurance over creation, competitiveness shifts accordingly.

Insight: Current policy rewards whoever can wait out uncertainty the longest—which usually means whoever has the most money, not whoever builds the best technology.

VII. What This Means for National Competitiveness

Individual company effects aggregate into national outcomes. If startups face higher barriers and incumbents consolidate, the result isn’t just reshuffled market share—it’s slower technology diffusion, reduced dynamism, and eventually lost competitive position relative to other countries.

How Capital Flows Change

Investors respond to uncertainty by demanding compensation. When patent validity can’t be tested quickly, financing terms incorporate higher risk premiums. Projects with narrow margins or fast deployment timelines become less attractive because legal uncertainty hangs over the critical development period.

The effect isn’t irrational. Investors are correctly pricing the risk they observe. The problem is that the risk comes from system dysfunction, not from anything inherent to the technology. Capital shifts toward companies that can absorb legal tail risk—not necessarily companies with the best ideas.

Concentration Follows

Over time, this dynamic produces market concentration. Large firms with defensive portfolios gain share because they can tolerate uncertainty that drives competitors out. Smaller, innovative entrants get acquired at distressed valuations or exit contested markets entirely. Fewer competitive entry points remain. Technology spreads more slowly because fewer companies are building.

Innovation doesn’t stop, but it becomes more centralized. The startup ecosystem that historically produced breakthrough technologies shrinks relative to incumbent-dominated development. The U.S. has long relied on startup-driven disruption as a competitive advantage. That advantage erodes when startups can’t navigate the patent system.

Quantifying the Drag

Our simulation measured national innovation throughput—how efficiently new technologies move from invention to deployment. The measure dropped from 0.69 under the original IPR design to 0.41 under current policy. That’s a 46% reduction in throughput coherence.

Countries don’t lose competitiveness because they stop inventing. They lose because they deploy more slowly than competitors. A nation that generates great ideas but can’t get them to market loses ground to countries with clearer paths from lab to product. Patent uncertainty aggregates from individual company impacts into national outcomes. Capital flows toward uncertainty tolerance rather than innovation. Markets concentrate as smaller players exit. Technology diffuses more slowly. IPR governance isn’t a procedural detail—it’s a lever that affects whether the U.S. maintains its edge in technology commercialization.

Insight: A country that can’t efficiently test patent validity transfers competitive advantage from its inventors to its litigators—and eventually to foreign competitors with cleaner systems.

VIII. Why AI Faces Elevated Risk

AI is the highest-stakes technology competition happening right now. It also happens to be unusually vulnerable to exactly the kind of patent uncertainty that current IPR policy creates. AI’s technical architecture—many layers of technology that must work together—means that patent problems propagate in ways they don’t in simpler industries.

The Stack Problem

AI isn’t one technology. It’s a stack: chips at the bottom, then networking, then infrastructure (cloud platforms, data centers), then model training software, then the models themselves, then applications built on top. Each layer depends on the ones below.

Patent uncertainty anywhere in this stack affects everything built above it. A questionable patent on networking technology creates risk for every AI application that needs fast data transfer. An unresolved chip patent affects every model trained on those chips. You can’t isolate the problem—it propagates.

In industries with simpler architectures, a company can often design around a single problematic patent. In AI, where the layers are deeply interdependent, that’s much harder. The whole stack is implicated.

Speed Mismatch

AI capabilities advance monthly. Competitive positions shift quarterly. A startup that has to wait three years for patent clarity might not exist in three years. The 38-month uncertainty half-life we measured vastly exceeds AI development cycles.

Traditional industries might tolerate extended uncertainty windows. AI can’t. By the time a dispute resolves, the technology may have moved on entirely. The company that should have built the next generation is stuck defending against claims about the last one.

Rational Responses Make Things Worse

When early validity review isn’t available, AI companies respond predictably—but the responses aren’t good for competition:

Vertical integration: Build everything in-house to avoid depending on external technology with uncertain IP status. Expensive, inefficient, but limits exposure.

Closed systems: Open standards and interoperability increase patent attack surface. Proprietary, closed architectures limit it. So companies build walls.

Seeking acquisition: Joining a large portfolio-holder provides defense that independent operation can’t. Many promising AI startups will rationally seek buyouts rather than face patent exposure alone.

These responses concentrate the market and reduce openness—exactly the opposite of what’s needed for healthy AI ecosystem development.

Independent Startups Face the Sharpest Disadvantage

The companies worst positioned are independent AI startups building infrastructure-layer technology. They operate in patent-dense territory (chips, networking, optimization). They lack portfolio depth for countersuits. They don’t have capital reserves for multi-year litigation. IPR was their primary defense mechanism—and it’s now largely unavailable.

The rational response is to seek acquisition by a portfolio-rich incumbent, or to avoid infrastructure-layer work entirely. Neither supports competitive markets. AI’s layered architecture, fast development cycles, and infrastructure-layer patent density make it uniquely vulnerable to IPR restrictions. The enclosure risk our simulation measured has more than doubled. Independent entry faces structural barriers. AI competitiveness depends on IPR access in ways that other sectors don’t.

Insight: AI’s architecture transforms patent uncertainty from a legal nuisance into a competitive barrier—and current policy has more than doubled that barrier.

IX. What We Expect to Happen

Predictions matter only if they can be checked. The thesis fails if AI-adjacent patent assertion and early settlements don’t rise measurably by Q4 2026, despite continued discretionary denials at the Patent Office. Here’s what we expect—and how to tell if we’re wrong.

Trajectory 4A — If Clampdown Continues

Assuming the discretionary denial regime stays in place through 2026, we predict:

More patent lawsuits in AI-adjacent sectors. A 20–30% increase in assertion filings, concentrated in the Eastern and Western Districts of Texas and other plaintiff-friendly venues. When IPR isn’t available to knock out weak patents early, litigation becomes the main arena.

Higher settlements before any merits decision. Defendants who can’t access IPR face a choice: fight for years in federal court, or settle. Many will settle. The average settlement value should rise.

More vertical integration. Companies that can’t rely on IPR to clear blocking patents will build more in-house and depend less on external technology. This is inefficient but rational.

Less independent deep-tech venture formation. Startups in patent-dense sectors face higher barriers. Investors will adjust. Expect capital to shift toward lower-exposure sectors or toward startups with incumbent backing.

Aging patent portfolios become hot commodities. PE and assertion funds will buy up old patents that would previously have been vulnerable to IPR challenge. The secondary market expands.

AI stack enclosure risk remains elevated. Enclosure index stays above 0.75 as uncertainty propagates through infrastructure layers.

Trajectory 4B — If Feedback Gets Restored

If courts or Congress restore judicial review of institution denials—without reopening the merits decisions—the dynamics reverse:

Institution denials become more consistent. Rule-like criteria replace discretionary factors.

Uncertainty half-life returns toward baseline. Resolution in 15–18 months rather than 34–38 months.

Fewer cost-driven early settlements. Defendants regain access to a meaningful validity check.

Reduced leverage at ITC. The International Trade Commission becomes less attractive as an alternative pressure point.

Slower portfolio aggregation. The defensive value of large patent holdings decreases relative to clampdown.

Continued competitive entry in AI infrastructure. Independent startups face a more navigable path.

Preservation of modular AI stack development. Open interfaces and interoperability remain viable strategies.

Innovation throughput recovers. System coordination and learning capacity return toward baseline levels.

The key insight: this path does not weaken patents. It restores feedback, allowing the system to learn and self-correct.

Failure Conditions

If these falsification conditions occur, the model needs revision. We state this explicitly because predictions without failure conditions aren’t predictions—they’re stories.

The simulation produces specific, testable forecasts about what happens under different policy paths. By Q4 2026, we’ll know whether the model holds. That’s how forecasting should work.

Insight: A model that can’t be proven wrong can’t be trusted when it claims to be right.

X. Conclusions and What Should Happen

Congress created IPR to provide fast, expert patent validity screening. Current policy has constrained that function. The Patent Office now exercises discretion that no one can effectively review, uncertainty persists longer than the system was designed for, and the actors best positioned to wait are gaining at the expense of those who need to build.

The Core Problem

The risk isn’t that patents are too strong or too weak. The risk is that uncertainty is replacing clarity. When validity questions can’t be resolved efficiently, the system rewards whoever can carry uncertainty longest. That’s usually whoever has the most money or the least need to operate productively.

The Patent Office has flexibility—but no accountability. Decisions can’t be reviewed. Errors can’t be corrected. The institution is operating without feedback.

The Common Framing Is Wrong

The IPR debate often gets framed as pro-patent versus anti-patent. That misses the point.

Restricting IPR isn’t pro-patent. It’s pro-uncertainty.

Strong patents benefit when the system can validate them. A patent that survives expert scrutiny is more credible than one that’s never been tested. What current policy protects isn’t strong patents—it’s untested patents.

The Fix Is Narrow

The simulation points to a targeted repair:

Restore judicial review of whether the Patent Office is following the law. Keep everything else the same.

If the Patent Office denies review based on factors Congress never authorized, challengers can appeal the legality of that denial. If the Patent Office grants review, that decision stays final. Merits decisions remain with expert judges. Courts don’t second-guess policy—they enforce statutory limits.

This is correction, not expansion. Congress designed IPR for validity screening. The repair restores that design.

What’s at Stake

For policymakers: IPR governance is a competitiveness lever. Current policy reduces innovation throughput, concentrates markets, and creates barriers to AI sector entry. Restoring feedback doesn’t weaken patents—it strengthens system credibility.

For investors: The policy shift redistributes value systematically. Adjust sector allocation and deal structures to account for elevated uncertainty. Recognize that portfolio companies face different exposure depending on their size and patent position.

Summary

The four trajectories in one line: Once early error correction is insulated from review, the system predictably shifts from merit screening to uncertainty arbitrage—unless feedback is restored, in which case most baseline functionality returns.

Insight: The choice isn’t between strong patents and weak patents—it’s between a system that can correct its errors and one that can’t.

About MindCast AI and This Analysis

What is MindCast AI?

MindCast AI is a predictive cognitive AI system designed to analyze how legal, economic, and institutional systems behave under stress and over time. Rather than predicting outcomes from static rules, MindCast AI builds Cognitive Digital Twins (CDTs)—computational representations of institutions, markets, and decision-makers that simulate how incentives, constraints, and information flow interact dynamically. CDTs allow modeling not only what a system permits on paper, but how the system actually evolves in practice as actors respond to uncertainty, delay, and strategic pressure.

What are Vision Functions?

Within each CDT, MindCast AI runs specialized analytical modules called Vision Functions. Vision Functions are structured lenses that evaluate specific causal domains—such as coordination efficiency, exploitation incentives, institutional learning capacity, or innovation throughput—using defined metrics and thresholds. Each Vision Function asks a narrow question (”Is this system coordinating?”, “Is uncertainty being exploited?”, “Can the institution still learn?”) and produces measurable outputs. Combined, Vision Functions allow MindCast AI to diagnose systemic failure modes, compare policy counterfactuals, and generate falsifiable foresight about how legal and economic systems will behave under alternative governance choices.

Vision Functions Used in This Analysis:

Institutional Coordination CDT — Measures system coordination integrity, exploitability, and correction feasibility

Causal Uncertainty Propagation CDT — Tracks uncertainty duration and dispute venue migration

Institutional Cognitive Plasticity CDT — Assesses institutional learning and adaptation capacity

National Innovation Throughput CDT (NIBE Vision) — Quantifies innovation drag and deployment coherence

AI Stack CDT — Models enclosure risk and capital concentration in layered technology systems

Sources and References

Primary Source:

Mark A. Lemley, “Patent Office’s Inter Partes Review Restrictions Violate the Law,” Bloomberg Law (October 27, 2025)

USPTO Policy Changes:

“Patent Office Moves to Limit Validity Challenges at Board,” Bloomberg Law (October 16, 2025)

“Patent Chief Takes Over Validity-Challenge Screening Role,” Bloomberg Law (October 17, 2025)

“Patent Judges Review Fewer Challenges as Agency Priorities Shift,” Bloomberg Law (August 11, 2025)

Former Director Commentary:

“Ex-Director Vidal Blasts Trump Patent Office’s Policy Changes,” Bloomberg Law (October 3, 2025)

Federal Circuit Developments:

“Federal Circuit Axes More Challenges to Patent Board Changes,” Bloomberg Law (November 6, 2025)

“Patent Office Tees Up Appeals Fight Over Unilateral Rulings,” Bloomberg Law (October 31, 2025)

“Patent Office Challenges Highlight Federal Circuit’s 2026 Slate,” Bloomberg Law (December 2025)

Industry Analysis:

“Year of Change, Transition, Recalibration: What Mattered in 2025 IP Practice,” IPWatchdog (December 28, 2025)

“U.S. Patent Litigation Trends in 2025: Patterns Behind the Numbers,” IPWatchdog (September 28, 2025)

“Changes Reducing IPR Institution Rate Have Increased Litigation Frequency and Cost,” Patent Progress (2020)

Practice Guidance:

“Efficiency at What Cost: The USPTO’s New PTAB Proposal Would Unfairly Strip Defendants of Legitimate Defenses,” King & Spalding (October 2025)

“Navigating the PTAB’s New Discretionary Denial Landscape: Strategic Shifts for Patent Challenges,” Fenwick(2025)

“Recent Changes to Discretionary Denial Procedures in Post-Grant Proceedings Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board,” Quinn Emanuel (2025)

“First Institutions Under Squires: Trends, Impact of Stipulations, and Practice Pointers,” Morgan Lewis (December 2025)

Startup and Investment Context:

“How Intellectual Property Protection Fuels Growth for Tech Startups,” ArentFox Schiff (2025)

“Intellectual Property and the Venture-Funded Startup,” MBHB (2025)

“The Role of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) in Startups and Innovation,” International Journal of Intellectual Rights Law (2025)

National Competitiveness:

“Innovation and IP Challenges in Key Sectors: Insights from Leadership 2025,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (2025)