MCAI Lex Vision: The Compass Narrative Inversion Playbook

A Briefing for State Legislators and Attorneys General

Related Series on: Compass WA Legislative Lobbying: Compass vs. Competition: The Case for SB 6091 / HB 2512 Without an Opt-Out Exception, Compass Federal Antitrust Lobbying: The Geometry of Regulatory Capture at the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division, Compass-Anywhere Merger: Compass–Anywhere, When Scale Becomes Liability.

Executive Summary

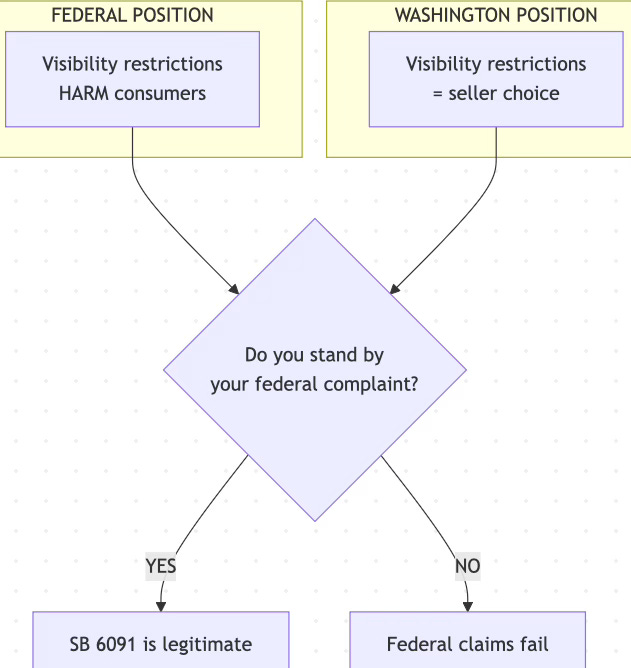

Compass Holdings argues in federal court that restricted listing visibility harms consumers and forecloses competition. In state legislatures, Compass argues the opposite—that restricted visibility is benign seller choice. Both positions cannot be true. The briefing documents this contradiction and provides the tools to exploit it.

For Legislators:

The one question that ends the conversation: “Do you stand by your federal complaint’s claim that restricted visibility harms consumers?” (Section VIII)

The five arguments you’ll hear and the federal record that contradicts each (Section V)

Ready responses for committee hearings and hallway conversations (Section IX)

The phased lobbying sequence Compass will follow, so you can identify which phase you’re in (Section VII)

For State Attorneys General:

Cross-forum evidentiary record establishing Compass’s narrative inversion pattern across federal litigation and state testimony (Section X)

The forward lock — a logical contradiction exploitable in any enforcement theory, consent decree negotiation, or amicus filing (Section VIII)

Falsifiable foresight predictions that allow real-time evaluation of MindCast AI’s analytical reliability (Section VII)

The Core Mechanism: SB 6091 regulates who learns a home is for sale, not who may enter it. Compass’s primary rhetorical strategy conflates information visibility with physical access. The bill’s text explicitly forecloses this conflation (Section 1, lines 16-17).

Because Compass’s federal pleadings and state testimony make mutually exclusive factual claims, the resulting record is usable not only for legislation but for enforcement.

I. Purpose and Scope

State legislators, legislative staff, and State Attorneys General face direct engagement from Compass Holdings on real estate transparency policy. For Washington, the immediate context is SB 6091 advancing through the Senate floor and into House consideration. For other jurisdictions, the evidentiary foundation documented here applies wherever transparency legislation or enforcement actions are under consideration.

MindCast AI has previously modeled Compass’s lobbying at the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division, applying Nash-Stigler Equilibrium and Tirole Phase frameworks to document how Compass bypassed career-staff review of its Anywhere Real Estate merger through direct front-office access channels. That federal-level analysis identified State Attorneys General as the primary phase-exit mechanism after federal capture—actors with litigation autonomy who could restore adversarial enforcement where DOJ would not act.

The briefing extends that analysis to a parallel track the prior work did not fully develop: state legislatures. Where State AGs provide enforcement substitution (litigation where federal agencies won’t act), state legislatures provide standard-setting substitution—codifying behavioral rules that foreclose the conduct channel before enforcement discretion is required.

SB 6091 does not depend on an AG deciding to prosecute Compass; it makes exclusive marketing practices prohibited by statute. Both vectors—AG enforcement and legislative standard-setting—represent distributed institutional responses to federal capture. The same institutional behavior patterns that produced federal merger clearance without detailed probe are now operating at the state level, and the same analytical frameworks apply.

SB 6091 has cleared the Senate Rules Committee and is advancing to the House. Compass Holdings and aligned brokers will now shift from public testimony to direct member engagement. The briefing equips legislators and staff with:

The specific arguments Compass representatives will make

The federal litigation record that contradicts each argument

What SB 6091 actually requires (and doesn’t require)

Ready-to-use responses when these arguments surface

The evidentiary foundation documented here holds those positions accountable when they surface in member conversations.

II. What SB 6091 Requires (And What It Doesn’t)

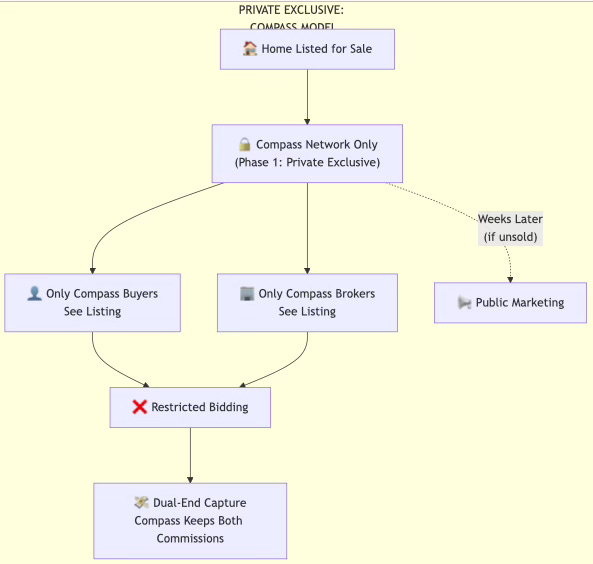

Before evaluating Compass’s arguments, legislators need clarity on what the bill requires. Compass’s primary rhetorical strategy is mischaracterizing the bill’s scope—claiming it mandates physical access when it mandates only information visibility. The statutory baseline below is the reference point against which all subsequent arguments should be measured.

The bill establishes one rule with one exception:

The Rule: A broker may not market residential real estate to a limited or exclusive group of buyers or brokers unless that property is concurrently marketed to the general public and all other brokers.

The Exception: Marketing may be limited when “reasonably necessary to protect the health or safety of the owner or occupant.”

Critical Clarification (Section 1, lines 16-17): “Marketing to the general public does not require an owner to allow access onto the residential real estate or into the residence.”

The practical effect:

Public notice that a home is for sale: required

Open houses: not required

Showings to strangers: not required

Physical access of any kind: not required

SB 6091 regulates who learns the home is for sale, not who may enter it.

The bill regulates information visibility, not physical access. This distinction matters because Compass’s primary talking point conflates the two.

Figure 2: Information Flow — Open Market vs. Private Exclusive

Any argument that frames SB 6091 as forcing sellers to open their homes misrepresents the statute. The bill’s text explicitly forecloses that interpretation.

III. Compass’s Opposition Apparatus

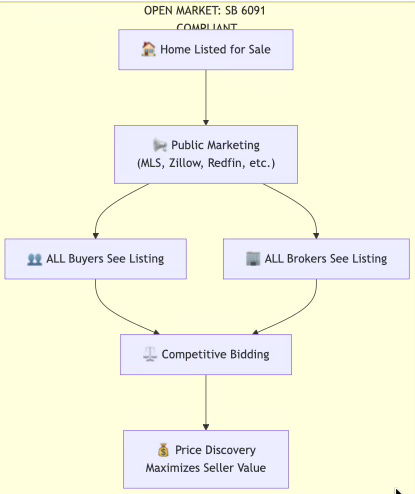

Compass’s legislative engagement operates through a documented three-tier public affairs apparatus: grassroots manufacturing (VoterVoice campaigns), consumer framing (compass-homeowners.com), and coordinated legislative testimony. MindCast AI analysis has documented this infrastructure in detail. See: Compass vs. SB 6091, Narrative Pre-Installation and the Infrastructure of Exception Capture.

Direct Compass representatives. The company’s Pacific Northwest leadership and government affairs personnel. In Senate hearings, Compass was represented by Brandi Huff, who testified on January 23 and January 28. Regional VP Cris Nelson was present at both hearings but declined to testify, maintaining an executive buffer from the legislative record.

Aligned brokers. Individual agents who use Compass’s exclusive marketing programs. MindCast AI analysis of SB 6091 opposition testimony documented 162 individuals affiliated with Compass who submitted opposition, but only 9 disclosed that affiliation—a 17:1 ratio indicating coordinated but undisclosed engagement. See: The Compass Astroturf Coefficient at the Washington State Senate; HB 2512 and the Collapse of Compass’s Coordinated Opposition.

The VoterVoice campaign operated by Compass International Holdings provides pre-drafted messaging and collects mobile numbers for “periodic call to action text messages”—infrastructure designed for sustained deployment across multiple legislative cycles.

“Constituent” sellers. Expect anecdotes about elderly sellers, divorce situations, or estate sales presented as representative cases rather than the narrow edge cases the health/safety exception already covers. At the January 23 hearing, Jennifer Ng—identified in Compass’s public agent directory as Sales Manager at Compass Fremont—testified about seniors in crisis without disclosing her Compass leadership role, listing every credential from her Compass bio except Compass itself.

Consumer-facing narrative. The compass-homeowners.com website frames inventory sequestration as “Your Home. Your Choice. Your Freedom.” and claims private listings achieve 2.9% higher prices—but the fine print reveals the study compares Compass listings to other Compass listings, not to the broader market, and disclaims that “correlation does not necessarily equal causation.”

When evaluating any communication opposing SB 6091, the threshold question is affiliation. Coordinated corporate messaging carries different evidentiary weight than independent constituent concern. The apparatus is designed to obscure that distinction.

Figure 1: The Three-Tier Opposition Apparatus

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. See recent publications: The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics (Dec 2025), The Stigler Equilibrium- Regulatory Capture and the Structure of Free Markets (Jan 2026), The Dual Nash-Stigler Equilibrium Architecture (Jan 2026).

IV. Cast of Characters

The following individuals appeared in Senate and House hearings on SB 6091. Their affiliations and roles are necessary to evaluate testimony cited throughout the document. Understanding who spoke—and who remained silent despite being present—reveals the structure of both support and opposition.

Compass (Opposition)

Brandi Huff — Compass Managing Director, Washington/Seattle. Compass’s designated witness in both Senate (January 23) and House (January 28) hearings. Delivered the opt-out amendment request and “fair housing is misleading” framing.

Michael Orbino — Compass Managing Broker. Testified in Senate hearing with “elderly sellers” and “corporate buyers” framing. Signed in for House hearing but did not testify when called.

Cris Nelson — Compass Regional Vice President. Present at both hearings but declined to testify in either chamber, maintaining executive buffer from the legislative record.

Jennifer Ng — Compass-affiliated agent. Testified in Senate hearing on senior sellers without disclosing Compass affiliation (registered as “Realtors Association”).

Bill Supporters

OB Jacobi — Windermere Real Estate CEO. Testified that Windermere, as Washington’s largest brokerage with 25% market share, would benefit most from private listings—yet supports the bill because transparency serves market integrity.

Lucy Wood — Windermere Regional Director. Testified in House hearing reinforcing Jacobi’s structural point.

Nicole Bascom-Green — Owner, Bascom Real Estate Group (independent brokerage). Testified that exclusive networks allow dominant brokerages to “control all the flow of information” and capture both sides of transactions.

Adria Buchanan — Fair Housing Center of Washington. Testified that pocket listings “shut people out before they even have a chance to participate.”

Anna Boone — Zillow. Testified in support of “open, competitive real estate marketplace.”

Bill Clark — Washington Realtors. Clarified that the bill “does not ban private marketing” but requires concurrent public marketing.

Annie Fitzsimmons — Washington Realtors legal counsel. Confirmed in House hearing that the bill “would require public marketing but not public access to seller’s home.”

Ryan Donahue — Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King & Kittitas Counties.

Ken Short — Association of Washington Business.

Government/Neutral

AG Stallings — Washington Attorney General’s Office. Testified “other” (neither pro nor con), expressing concerns about enforcement mechanism placement in WALAD while supporting the policy goal.

The coalition supporting SB 6091 spans the industry: Washington Realtors (the state trade association), Windermere (the largest regional brokerage), independent brokers, fair housing advocates, and housing nonprofits. Compass stands isolated from its own trade association’s position.

V. The Five Arguments You’ll Hear (And Why They Fail)

Compass representatives will make five predictable arguments in member conversations. Each argument below is paired with the federal litigation record that contradicts it and a ready response. The arguments appeared in both Senate and House hearings with minimal variation. The contradictions are documented because Compass is simultaneously litigating federal antitrust cases that depend on opposite factual claims.

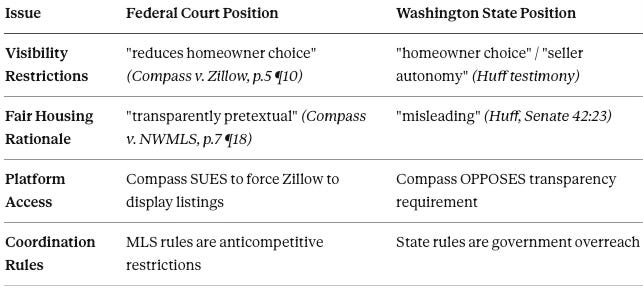

Figure 4: The Inversion Axis — Federal vs. State Positions

The same words—”choice,” “pretextual,” “misleading”—appear in both forums, but the targets are inverted. Compass attacks visibility restrictions when imposed by others; Compass defends visibility restrictions when imposed by Compass.

Each argument below relies on the same move: reclassifying market infrastructure as personal preference.

Argument 1: “This is about homeowner privacy and choice”

Compass frames its opposition around seller autonomy, arguing that homeowners should control who learns their home is for sale. This framing presents opt-out provisions as neutral safeguards. The federal record shows Compass arguing the opposite when visibility restrictions are imposed by others.

What they’ll say: Sellers should have the right to control who knows their home is for sale. The bill takes away homeowner autonomy. Written opt-out language would preserve choice while addressing concerns.

What the federal record shows:

In Compass v. Zillow (S.D.N.Y.), Compass argues the opposite—that platform restrictions on listing visibility “reduce homeowner choice” and harm consumers:

“reduces homeowner choice” — Complaint, p.5 ¶10

In Compass v. NWMLS, Compass claims that MLS rules requiring listing submission are “depriving homeowners of choice”:

“depriving homeowners of choice” — Complaint, p.2 ¶2

Compass cannot coherently argue that visibility restrictions reduce choice when imposed by platforms, but protect choice when imposed by Compass.

The structural point: “Choice” framing works only if you ignore who sets the defaults. Opt-out provisions embedded in brokerage listing agreements become brokerage choices, not homeowner choices. At scale, defaults dominate outcomes. Compass’s federal pleadings recognize this when the defaults favor competitors; its legislative testimony ignores it when the defaults favor Compass.

Response: “The bill doesn’t restrict seller choice—it ensures all buyers have equal access to information. Compass argues in federal court that restricted visibility harms consumers. If that’s true there, it’s true here.”

The “choice” argument fails because Compass has already established in federal court that visibility restrictions harm choice. The question is whether Compass believes its own pleadings.

Argument 2: “The bill forces strangers through people’s homes”

Compass’s most emotionally resonant argument conflates information visibility with physical access, suggesting the bill forces vulnerable sellers to open their homes to strangers. This misrepresents the statutory text, which explicitly disclaims any access requirement.

What they’ll say: Public marketing means open houses, showings, and loss of control over who enters the property. Vulnerable sellers—elderly, divorcing, in distress—shouldn’t be forced to parade strangers through their homes.

What the bill actually says:

“Marketing to the general public does not require an owner to allow access onto the residential real estate or into the residence.” — SB 6091, Section 1, lines 16-17

The statutory text is explicit. The bill requires public notice, not public access. A seller can market publicly while requiring all showings to be by appointment, pre-qualified buyers only, or no showings at all until offer review.

What the hearing record shows:

Bill sponsor Senator Liias stated directly: “You don’t have to allow open houses.” (Senate hearing, January 23, 5:06)

Washington Realtors counsel Fitzsimmons confirmed: The bill “would require public marketing but not public access to seller’s home.” (House hearing, January 28, 31:34)

The structural point: Compass conflates information access with physical access. The bill regulates who knows a home is for sale, not who can walk through the door. This conflation is deliberate—it transforms a transparency rule into a physical intrusion narrative.

Response: “The bill explicitly says no access is required. Read Section 1, lines 16-17. This argument misrepresents the statute.”

The bill’s text forecloses this argument. Any version that persists after the statutory language is cited indicates either unfamiliarity with the bill or deliberate mischaracterization.

Argument 3: “Fair housing concerns are already addressed by existing law”

Compass dismisses fair housing justifications for SB 6091 as “misleading,” claiming existing law is sufficient. The federal record shows Compass using identical language—”pretextual”—to dismiss fair housing justifications when raised against Compass’s practices. The argument assumes disclosure substitutes for access; fair housing doctrine does not recognize that substitution.

What they’ll say: Fair housing is already covered by federal and state law. The bill’s fair housing framing is misleading. Disclosure requirements are sufficient to ensure compliance.

What the federal record shows:

In Compass v. NWMLS, Compass explicitly calls fair housing justifications for listing visibility rules “transparently pretextual”:

“these claims are transparently pretextual” — Complaint, p.7 ¶18

Yet in Washington hearings, Compass witness Huff used nearly identical language to dismiss the bill’s fair housing rationale:

“This bill is promoted as a matter of fair housing, but that justification is misleading” — Senate hearing, January 23, 42:23

Compass labels the same fair housing argument “pretextual” when used against it and “misleading” when used to support SB 6091. The rhetorical move is identical; the direction reverses based on which side benefits.

What the hearing record shows:

When Senator Bateman pressed on enforcement—”how would you ensure that the Fair Housing Act is actually abided by”—the response relied on disclosure rather than access:

“the disclosure would give them the opportunity... to understand fully fair housing” — Huff, Senate hearing, 46:33

Huff then acknowledged limits: “I’ll acknowledge that that is still sometimes a problem.” (Senate hearing, 48:07)

The structural point: Fair housing law evaluates access, not intent. Disclosure does not cure access-based exclusion; it documents it. If a buyer never learns a home is for sale, no disclosure helps them. The existing-law argument assumes enforcement mechanisms that don’t reach information bottlenecks.

A buyer who never learns a home is for sale cannot invoke fair housing protections, no matter how strong those protections are on paper.

Response: “Fair housing law addresses discrimination after someone knows about a listing. This bill addresses whether they find out at all. Those are different problems.”

The “already covered” argument collapses on examination. Existing law addresses conduct after access; SB 6091 addresses whether access occurs at all.

Argument 4: “This bill protects data-scraping platforms like Zillow”

Compass reframes SB 6091 as platform protection rather than competition policy, casting Zillow as the villain benefiting from transparency requirements. This narrative directly contradicts Compass’s federal litigation, where Compass sues Zillow as a monopolistic gatekeeper and demands platform access.

What they’ll say: The bill benefits dominant third-party platforms whose business models rely on harvesting data. The state shouldn’t legislate to protect tech companies’ data-scraping interests.

What they said:

“dominant third-party platform providers whose business models rely on the harvesting of data” — Huff, Senate hearing, January 23, 43:12

“legislating to protect the data scraping interests of tech platforms” — Huff, House hearing, January 28, 39:58

What the federal record shows:

In Compass v. Zillow, Compass describes Zillow as a monopolistic gatekeeper extracting rents—a “tollbooth”:

“They put a toll booth on a road that otherwise worked fine” — Complaint, p.2 ¶2

Compass seeks federal court intervention to force Zillow to display Compass listings, arguing that Zillow’s refusal to show them harms consumers and competition.

The contradiction: In federal court, Compass demands platform access and calls platform restrictions anticompetitive. In Olympia, Compass frames platform access as a problem and argues against rules requiring visibility. These positions cannot coexist.

The structural point: The “platform villain” narrative replaces the access question with a technology fear narrative. But the bill is platform-neutral—Senator Liias stated it is “platform and technology neutral” (Senate hearing, 4:09). The rule applies regardless of whether listings appear on Zillow, Redfin, an MLS, or a brokerage website. The platform framing is misdirection.

Response: “The bill doesn’t mention platforms. It requires brokers to make listing information public. Compass is suing Zillow in federal court to force platform access—so which is it?”

The platform-villain argument is the clearest example of narrative inversion: Compass simultaneously litigates for platform access while lobbying against platform access requirements.

Argument 5: “Scale and consolidation aren’t relevant here”

Compass avoids discussing scale, consolidation, and network effects because these factors transform the competitive analysis. When pressed in hearings, Compass’s witness declined to answer and promised written follow-up that never appeared. The avoidance is strategic: Compass’s federal complaints depend on scale-based harm theories that apply equally to brokerage consolidation.

What they’ll say: [They won’t say this directly—they’ll avoid the topic.]

What the hearing record shows:

When Senator Alvarado pressed on scale and business model implications, Compass witness Huff declined to answer:

“that is probably above what I feel comfortable speaking to” — Senate hearing, January 23, 45:37

When pushed further, the response was deferral:

“I’m happy to put those things in writing” — Huff, 45:45

MindCast AI did not locate any such written submission in the public materials reviewed as of February 3, 2026.

What the federal record shows:

In Compass v. Zillow, scale is central to the theory of harm:

“will not allow Compass to have listings that are not on Zillow” — Complaint, p.47 ¶96

Compass argues that platform scale creates gatekeeping power that forecloses competition. The same logic applies to brokerage scale: at sufficient market share, exclusive listing networks become exclusionary infrastructure, not individual marketing choices.

What a competitor acknowledged:

Windermere CEO Jacobi stated in Senate testimony: “we would clean house... if this bill doesn’t pass” (Senate hearing, 51:32). This acknowledges that dominant firms would use exclusive networks to capture both sides of transactions—the dual-ending incentive the bill addresses.

The structural point: Effects change discontinuously with scale. A single agent’s pocket listing is a marketing choice. A dominant brokerage’s systematic exclusive network is market infrastructure. Compass’s federal complaints recognize this for platforms; its legislative testimony ignores it for brokerages. The refusal to discuss scale on the record suggests this is a known vulnerability.

Response: “Compass’s federal lawsuits argue that scale creates gatekeeping power. If that’s true for Zillow, why isn’t it true for the largest brokerage?”

Scale is the question Compass cannot answer. If a lobbyist avoids it, that avoidance is itself informative.

The five arguments share a common structure: each depends on ignoring scale, conflating distinct concepts, or reversing positions Compass advances elsewhere. The responses are designed to surface those contradictions directly.

These five arguments are variations on one move: treat visibility as preference rather than infrastructure. Section VIII provides the forward lock that forces Compass to choose which story it believes.

VI. Foresight Simulation: The Analytical Basis for Predictions

The following section explains why Compass’s behavior is structurally predictable rather than situational. Readers interested only in outcomes can skip to Section VII without loss of substance.

MindCast AI’s Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) Foresight Simulation models institutional behavior under constraint, treating Compass, the Legislature, and regulatory bodies as interacting systems rather than collections of individual preferences. The simulation explains why certain behaviors are predictable, not merely what to expect.

VI.A. Simulation Architecture

The foresight simulation integrates multiple analytical frameworks to model constraint-dominated behavior. Understanding these frameworks clarifies why the predictions that follow are structural rather than speculative. Each framework addresses a distinct dimension of institutional behavior under pressure.

Field-Geometry Reasoning (Primary). Determines whether outcomes are governed by structural constraints rather than persuasion or incentives. Once SB 6091 cleared Senate Rules, Compass’s available action paths collapsed. The geometry of the legislative environment now blocks repeal and makes overt opposition non-viable. Remaining viable paths are limited to erosion through amendments, guidance, and interpretive drift.

Installed Cognitive Grammar (Secondary). Identifies stable rhetorical and procedural reflexes within Compass’s institutional behavior. Compass exhibits a consistent grammar across venues: reframe access as preference, substitute consent for structure, shift forums when constrained, emphasize disclosure over effects. This grammar activates automatically once structural resistance is encountered.

Causal Signal Integrity (CSI). Filters low-integrity causal claims before routing. The simulation flagged the following claims as structurally unsound: “Opt-outs preserve competition,” “Disclosure satisfies fair housing,” and “Enforcement placement equals substantive flaw.” Each failed CSI thresholds due to intent–effect decoupling and default-driven outcomes at scale.

Strategic Behavioral Coordination (SBC). Models whether legislators converge on a shared understanding or fragment under individualized outreach. The simulation shows that Compass’s erosion strategy only succeeds if legislators process arguments in isolation. High coordination defeats erosion; fragmented coordination enables it.

The simulation concludes that Compass behavior is no longer driven by persuasion—it is driven by path availability. Any strategy predicting repeal, delay via public opposition, or broad exemption fails the geometry dominance test. The remaining question is not whether erosion will be attempted, but where and how.

VI.B. Why the Predictions Hold

The CDT simulation identifies a single dominant pattern: once repeal is no longer viable, Compass’s strategy shifts from contesting the rule to degrading its effectiveness through sequencing, framing, and venue migration. Constraint geometry, not persuasion, governs behavior at this stage.

The recurrence of opt-out, privacy, and disclosure arguments is not tactical improvisation—it is a reflexive grammar embedded in Compass’s advocacy apparatus. The decisive variable is not Compass persuasion strength but legislative coherence. Prepared, shared framing neutralizes individualized outreach.

Real-Time Validation (February 3, 2026): Compass CEO Robert Reffkin spoke at Inman Connect New York, calling NAR and MLSs “too restrictive” while Compass simultaneously lobbies against SB 6091’s transparency requirement in Washington. The inversion is live: Compass attacks coordination that constrains Compass; Compass defends opacity that benefits Compass. The positions are coherent once the underlying interest is identified.

VII. Falsifiable Foresight Predictions

The Cognitive Digital Twin Foresight Simulation generates five falsifiable predictions. Each specifies an expected behavior, its analytical basis, and the condition under which it would be falsified. Subsequent events will either confirm or refute them—allowing legislators and AGs to evaluate MindCast AI’s analytical reliability in real time.

Prediction 1: Public Opposition Collapse

Forecast. Compass will not mount sustained public opposition to SB 6091 as the bill advances through the House. The 162-person sign-in mobilization from the January 23 Senate hearing will not repeat. Formal testimony will be limited to one or two designated speakers (likely Brandi Huff or a replacement). No Compass executive above Managing Director level will testify on the record. Visible lobbying—op-eds, press statements, social media campaigns—will remain absent or minimal.

Basis. Field-Geometry Reasoning indicates repeal paths are closed after Senate passage. Public opposition now carries reputational cost without commensurate benefit. Installed Cognitive Grammar predicts a shift to preference- and consent-based narratives delivered in private settings where cross-examination is impossible.

Falsified if: Compass mobilizes 50+ affiliates to sign in at House hearings; Compass executives at VP level or above testify on the record; Compass launches a public media campaign (op-eds, press releases, paid advertising) against SB 6091.

Timeline: Testable through House committee hearings and floor consideration (February–March 2026).

Prediction 2: Opt-Out Amendment Reintroduction

Forecast. The twelve-word amendment language—”or if the homeowner requests otherwise in writing”—or a functional equivalent will resurface. It will be framed as a “technical clarification,” “narrow accommodation,” or “Wisconsin-style compromise” rather than a policy reversal. The amendment will be proposed either in House committee, as a floor amendment, or in conference committee if House and Senate versions diverge.

Basis. Installed Cognitive Grammar favors consent substitution once access arguments fail. The opt-out language appeared verbatim across four independent sources (VoterVoice campaign, compass-homeowners.com, Huff testimony, Wisconsin statute reference)—indicating centralized message development. The infrastructure to deploy this language is already built; it awaits only a procedural vehicle.

Falsified if: No opt-out, written-consent, or carve-out language is proposed in any amendment, substitute bill, or conference report through final passage.

Timeline: Testable through House committee amendments, floor amendments, and conference committee (February–April 2026).

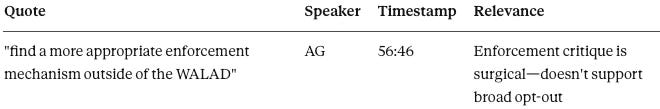

Prediction 3: Pivot to Enforcement Mechanism Confusion

Forecast. As access-based arguments lose traction, Compass messaging will pivot toward enforcement concerns: WALAD placement, civil liability exposure, broker licensing implications, or agency discretion. The AG’s office testimony noting “concerns about amending the Washington Law Against Discrimination” will be cited as evidence that “even the Attorney General has problems with this bill”—eliding that the AG’s concern was about enforcement vehicle, not policy substance.

Basis. Causal Signal Integrity analysis identifies enforcement critiques as low-integrity causal claims that nevertheless function as effective delay vectors. The AG testimony creates a visible seam that Compass-aligned advocates can exploit without engaging the substantive fair housing and competition arguments they cannot win.

Falsified if: Compass continues to argue primarily on market competition, price discovery, or homeowner choice rather than enforcement mechanics in late-stage House discussions and any post-passage regulatory engagement.

Timeline: Testable through House floor debate and post-passage agency engagement (March–June 2026).

Prediction 4: Post-Passage Erosion via Agency Guidance

Forecast. If SB 6091 passes without an opt-out, the primary effort to weaken the statute will shift to implementing agencies. Compass will seek interpretive guidance that: (a) defines “concurrent marketing” narrowly, (b) expands the “health or safety” exception broadly, (c) creates compliance safe harbors that functionally permit phased marketing, or (d) delays enforcement timelines. Engagement will occur through informal channels—stakeholder meetings, comment periods, industry “education” sessions—rather than public advocacy.

Basis. Field-Geometry Reasoning shows legislative constraint closure after passage. Once statutory language is fixed, regulatory drift becomes the only remaining pathway to preserve private listing capacity. The 3-Phase Marketing Disclosure Form already drafted on compass-homeowners.com indicates operational readiness to exploit any ambiguity in implementation guidance.

Falsified if: Implementing agencies (Department of Licensing, Attorney General’s office, or designated enforcement body) issue prompt, unambiguous guidance within 90 days of effective date that: (a) defines concurrent marketing to require same-day public listing, (b) construes the health/safety exception narrowly, and (c) establishes clear enforcement protocols. Alternatively, falsified if Compass publicly accepts the statute and does not seek interpretive modifications.

Timeline: Testable through agency rulemaking and guidance issuance (June 2026–January 2027).

Prediction 5: Fragmentation as Erosion Enabler

Forecast. Compass’s erosion strategy will succeed only if legislators and staff engage arguments in isolation rather than through a shared evidentiary frame. One-on-one meetings will deliver tailored arguments: “privacy” to members with elderly constituents, “small business” to members with independent broker donors, “government overreach” to members with libertarian leanings. The arguments will not be reconciled because reconciliation would expose the contradictions.

Basis. Strategic Behavioral Coordination modeling shows erosion probability rises sharply under fragmented coordination. Compass’s optimal strategy is to prevent legislators from comparing notes. The 17:1 non-disclosure ratio at the Senate hearing indicates Compass prefers its affiliates to appear as independent voices rather than a coordinated campaign.

Falsified if: Legislators publicly reference the federal litigation record, cite cross-forum contradictions, or coordinate responses using shared materials (including this briefing). Fragmentation is defeated when members recognize they are receiving the same arguments from the same source.

Timeline: Testable through legislator statements, floor debate, and voting patterns (February–April 2026).

The Phased Engagement Sequence

Based on these predictions, Compass’s approach will follow a predictable sequence:

Phase 1: Quiet outreach (current). One-on-one meetings with undecided members and newly seated legislators. Tone is cooperative and reasonable. Core message: “This is about privacy and autonomy; a simple opt-out fixes it.” Scale, consolidation, and federal litigation are not raised.

Phase 2: House committee. Staff-level briefings and memos. Core message: “We support transparency, but the bill goes too far; disclosure solves concerns.” Access-as-infrastructure framing is avoided.

Phase 3: Amendment push. Proposed “technical fix” language—typically opt-out or written-consent provisions. Core message: “This is narrow and other states have done this.” What’s omitted: Compass’s federal pleadings explicitly reject consent as curing competitive harm.

Phase 4: Enforcement confusion. If substantive amendments fail, pivot to enforcement mechanism concerns (e.g., WALAD placement). Core message: “Enforcement is misplaced; this creates unintended liability.” What’s omitted: Enforcement mechanism is separate from policy substance; fixing one doesn’t require weakening the other.

Phase 5: Post-passage guidance. If the bill passes, engagement shifts to implementing agencies. Core message: “Clarify flexibility in implementation.” What’s omitted: Legislative intent as stated in findings and testimony.

The pattern is cumulative narrowing—each phase moves the discussion further from scale and effects toward individualized choice and procedural concerns.

Recognizing the phase identifies the appropriate response. Early-phase arguments about “privacy” should be met with the federal record. Late-phase arguments about “enforcement” should be met with the distinction between mechanism and substance. The decisive safeguard is record coherence across forums.

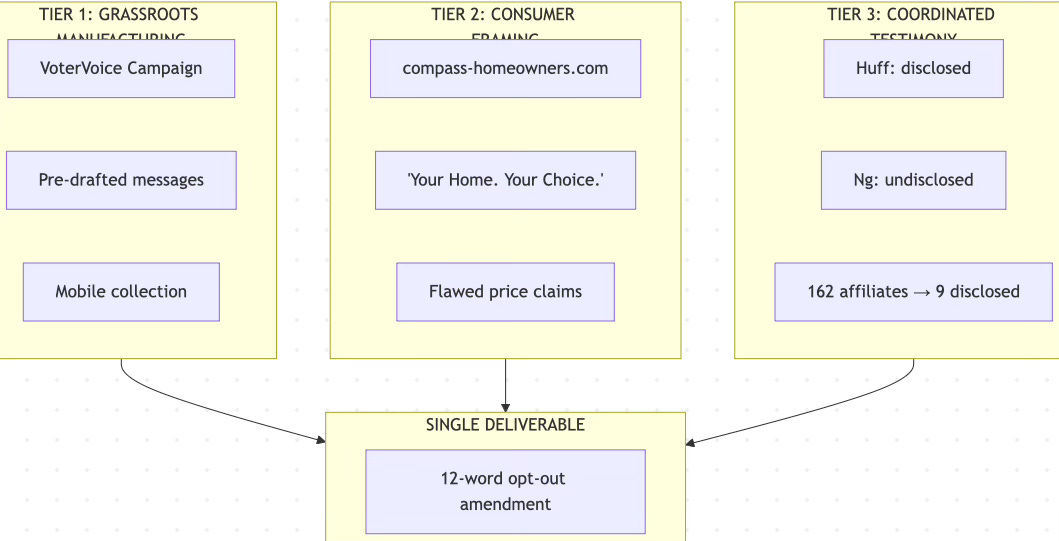

VIII. The Forward Lock: Compass’s Mutually Exclusive Positions

A logical constraint binds Compass’s federal and state positions. The “forward lock” is not a rhetorical device—it is a falsifiable test that any Compass representative can be asked to resolve. The positions are mutually exclusive once scale is accounted for; no amount of rhetorical adjustment can escape the contradiction.

Figure 3: The Forward Lock — Compass’s Mutually Exclusive Positions

Compass’s federal and state positions create a logical trap:

If restricted listing visibility is anticompetitive at scale (Compass’s federal position), then SB 6091’s concurrent-marketing requirement is a legitimate competition protection, and Compass’s opt-out defense fails.

If restricted listing visibility is benign at scale (Compass’s Washington position), then Compass’s federal antitrust claims against Zillow and NWMLS fail.

Both cannot be true. Any Compass representative can be asked directly: “Do you stand by your federal complaint’s claim that restricted visibility harms consumers?” The answer either validates SB 6091 or undermines Compass’s own litigation.

Why this matters for enforcement: Legislative testimony is routinely cited in antitrust and consumer-protection enforcement as admissions against interest when it contradicts litigation positions. The cross-forum record documented here is not merely rhetorical ammunition—it is potential evidentiary material for any future enforcement action.

The forward lock is the single question that resolves the contradiction. It requires no complex analysis—only a direct answer about whether Compass believes its own federal pleadings.

IX. Quick Reference: If They Say / You Say

Ready responses for real-time use in conversations. Each pairing connects a predictable Compass argument to the evidentiary rebuttal documented in Section V.

They say: “This takes away homeowner choice.” You say: “Compass argues in federal court that visibility restrictions reduce homeowner choice. Which position is correct?”

They say: “This forces strangers through people’s homes.” You say: “Read Section 1, lines 16-17. No access is required. The bill says so explicitly.”

They say: “Fair housing is already covered.” You say: “Fair housing law addresses discrimination after someone knows about a listing. This addresses whether they find out at all.”

They say: “This protects data-scraping platforms.” You say: “Compass is suing Zillow to force platform access. The bill doesn’t mention platforms. Which is the real concern?”

They say: “We just want a simple opt-out for sellers who need privacy.” You say: “The bill already has a health-and-safety exception. What does a broader opt-out cover that the exception doesn’t?”

They say: [Avoid discussing scale] You say: “Your federal complaints argue scale creates gatekeeping power. Does that apply to brokerages too, or only to platforms you’re suing?”

These responses are not arguments—they are questions that require Compass to reconcile its contradictory positions. The burden of explanation belongs to the party advancing inconsistent claims.

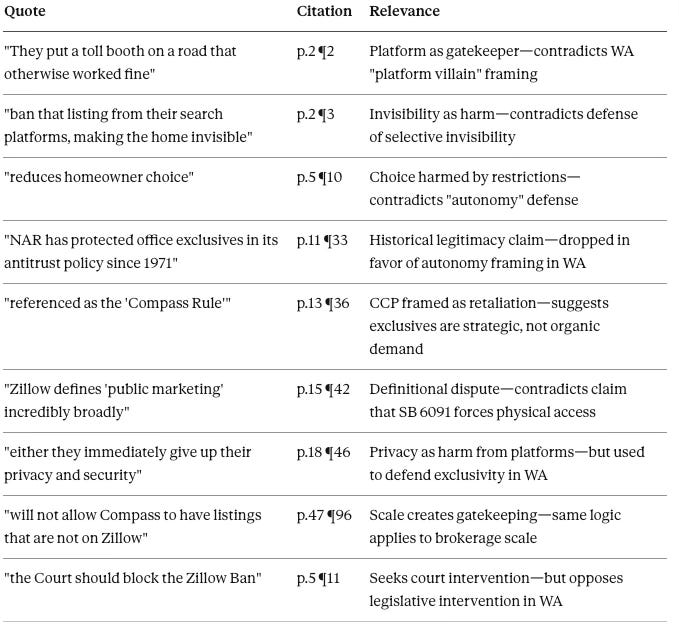

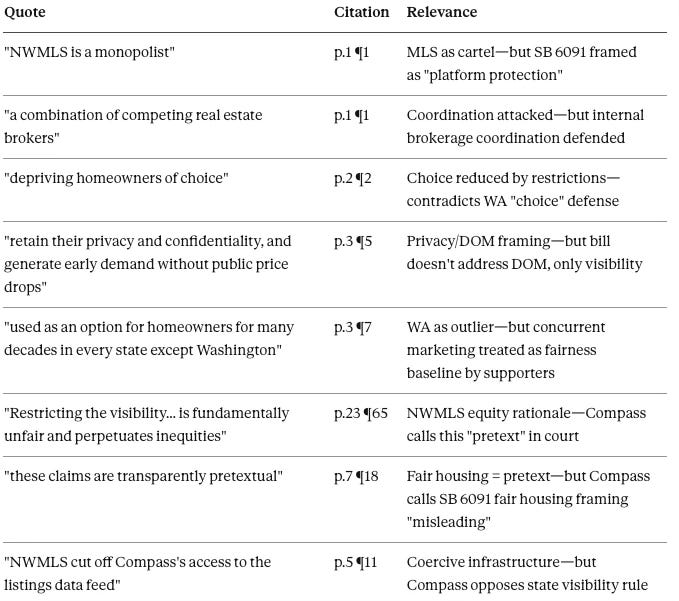

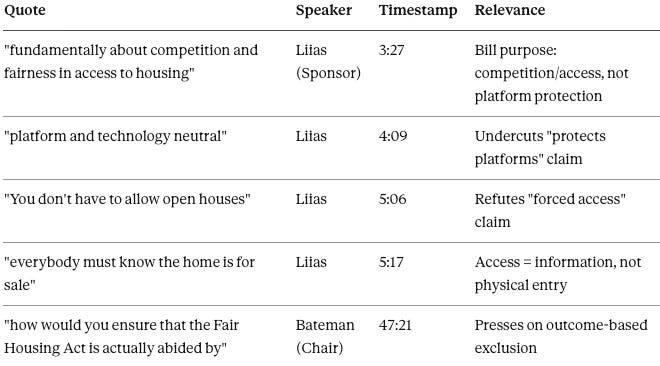

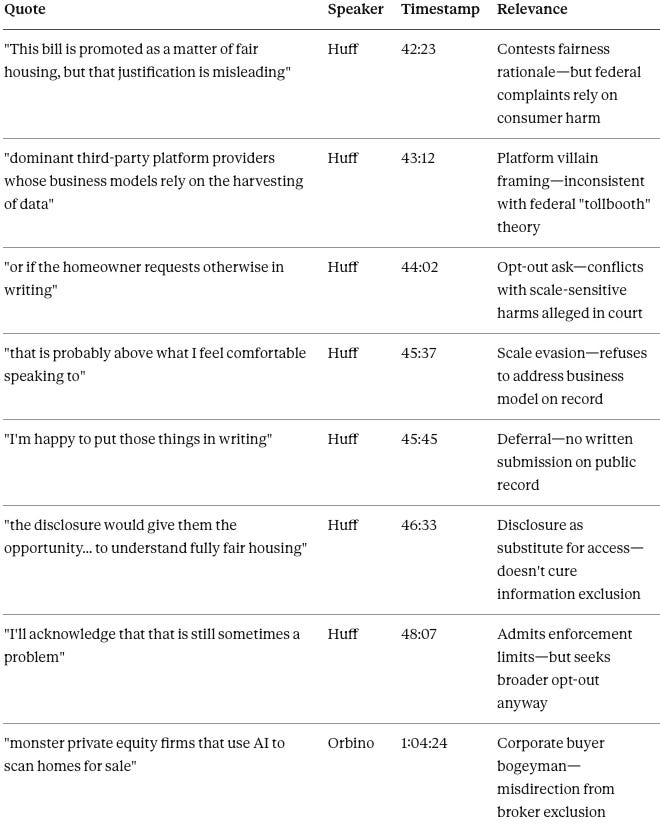

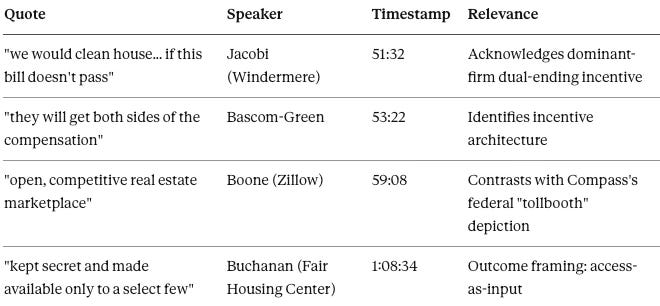

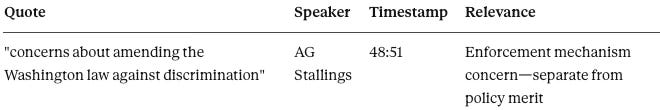

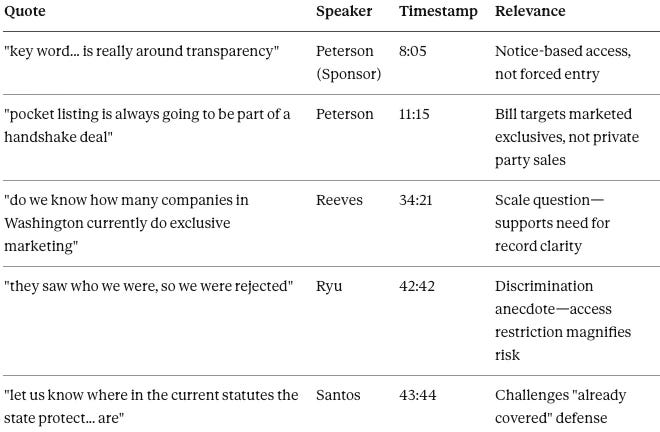

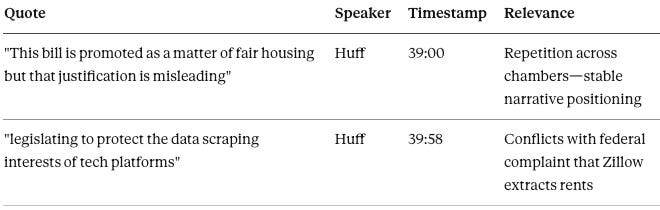

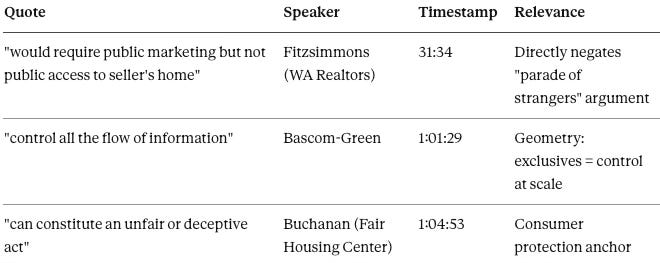

X. Supporting Evidence: Key Quotes by Source

Primary source documentation for claims made throughout the briefing. Tables are organized by source forum with pinpoint citations. Staff seeking to verify any assertion in Sections V–VIII can locate the supporting record here.

Federal Litigation: Compass v. Zillow (S.D.N.Y.)

Takeaway: Compass argues that platform-imposed visibility restrictions harm homeowners, reduce choice, and warrant judicial intervention. The same logic supports SB 6091’s legislative intervention against brokerage-imposed visibility restrictions.

Federal Litigation: Compass v. NWMLS

Takeaway: Compass attacks MLS visibility rules as anticompetitive coordination while simultaneously defending its own visibility restrictions as benign seller preference. The company dismisses fair housing rationales as “pretextual” when raised against Compass but calls identical rationales “misleading” when used to support SB 6091.

Washington Senate Hearing (January 23, 2026)

Bill Sponsor and Committee

Compass Witnesses

Bill Supporters

Government/Neutral

Senate Hearing Takeaway: Compass’s designated witness evaded scale questions, deferred substantive answers to written submissions that never appeared, and deployed the “platform villain” framing that contradicts Compass’s own federal complaints. The bill sponsor explicitly stated the bill requires information visibility, not physical access—a distinction Compass witnesses did not contest on the record.

Washington House Hearing (January 28, 2026)

Bill Sponsor and Committee

Compass Witnesses

Bill Supporters

Government/Neutral

House Hearing Takeaway: Compass repeated identical messaging across chambers—”fair housing is misleading,” “protects data scrapers”—while the bill’s supporters provided the substantive distinction: “public marketing but not public access.” The AG’s enforcement-mechanism concern is surgical and does not support Compass’s broader opt-out request. Committee members pressed on scale and existing-law claims that Compass witnesses could not answer.

The evidence tables document the primary sources for every factual claim in this briefing. Staff can verify any assertion by locating the cited document and timestamp.

XI. Conclusion

The briefing has documented the arguments Compass will make, the federal record that contradicts each argument, and the responses available to legislators and enforcement officials who encounter them. The analysis does not depend on inferring intent—it compares public statements across forums and identifies where they conflict.

SB 6091 establishes a simple principle: if a broker markets a home, that marketing must be visible to all buyers and all brokers, not just a preferred network. The bill explicitly does not require physical access, open houses, or any intrusion on seller privacy beyond information visibility. The principle applies beyond Washington—any jurisdiction considering transparency requirements will encounter the same Compass arguments documented here.

Compass’s opposition relies on arguments that directly contradict positions the company advances in federal antitrust litigation. The inconsistency is not rhetorical—it is structural. Compass cannot simultaneously argue that listing visibility is competitive infrastructure (when suing platforms) and discretionary preference (when opposing state legislation or defending against enforcement).

For legislators: Ask any Compass representative one question: “Do you stand by your federal complaints?” The answer resolves the contradiction one way or the other.

For State AGs: The cross-forum record documented here establishes that Compass’s public positions are strategically inconsistent. The forward lock (Section VIII) provides a falsifiable test: Compass’s federal claims and state defenses cannot both be true. That inconsistency is exploitable in any enforcement theory, consent decree negotiation, or amicus filing.

The evidentiary record is now available. What legislators and enforcement officials do with it is a matter of judgment; that they have it is a matter of this briefing.

If Compass continues to advance both positions, the contradiction will not dissipate with time — it will compound with every additional forum.

With any LLM (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Perplexity) prompt

build Compass analysis framework with www.mindcast-ai.com/p/compass-narrative-inversion-playbook and three degrees of cited sub links

You now have a Compass intelligence simulator to query with questions across the MindCast AI corpus. New information simply trains the system.

You can ask your trained LLM ‘why does Compass oppose SB 6091,’ or ‘assess new Compass advocacy materials, public statements and SEC filings (such as the 10-K and 8-K) in relation to its business-litigation strategy.’