MCAI Economics Vision: The Stigler Equilibrium- Regulatory Capture and the Structure of Free Markets

Why Enforcement Must Compete to Keep Markets Free

See companion studies: The Dual Nash-Stigler Equilibrium Architecture, Behavioral Settlement and Inquiry Sufficiency as Runtime Constraints (Jan 2026), Federal Antitrust Breakdown as Nash-Stigler Equilibrium, Not Accident, The Stigler Equilibrium Series, Installment I on Harm Clearinghouse (Jan 2026), Comparative Externality Costs in Antitrust Enforcement, A Nash–Stigler Foresight Study of Federal Enforcement Equilibria, Live Nation as Anchor, Compass–Anywhere as Validation (Jan 2026), Why the DOJ Banned Algorithms but Blessed a Mega-Brokerage (Jan 2026).

Executive Summary

Free markets require enforcement. Captured enforcement is not enforcement. Capture is the predictable equilibrium when enforcement is routed through a single decisive chokepoint and faces concentrated beneficiaries and diffuse victims. The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium (ECE) names that structural outcome.

Nobel laureate George Stigler’s 1971 theory of regulatory capture is not an argument against regulation. Stigler’s theory identifies the structural conditions under which regulation fails—and implies the structural conditions under which regulation succeeds. Commentators who invoke “free markets” against all enforcement have not read Stigler carefully. Stigler showed that enforcement routed through a single decisive chokepoint facing concentrated beneficiaries and diffuse victims produces capture as equilibrium. The solution is not zero enforcement. The solution is institutional competition that makes capture investment costly and uncertain.

Contemporary federal enforcement exhibits the structural conditions Stigler identified. The Department of Justice Antitrust Division, the Federal Trade Commission, the Department of Commerce, and the United States Patent and Trademark Office all face concentrated beneficiaries with high capture incentives and diffuse victims with low organization capacity. All four exhibit capture. The pattern is not partisan—capture appears across administrations because the mechanism is structural.

The market consequences are severe. Captured enforcement does not preserve market freedom. Captured enforcement enables private coercion to substitute for price competition. When merger review clears anticompetitive transactions, when consumer protection defers to future rulemaking, when export licenses route through political access, when patent examination favors repeat players—markets become less free, not more. The beneficiaries are not “the market.” The beneficiaries are concentrated actors who have substituted political investment for competitive performance.

Stigler’s framework implies a solution: institutional competition. When multiple enforcement venues share authority, capture investment must target all venues simultaneously. Distributed capture is expensive, uncertain, and therefore less attractive. State attorneys general, private enforcement, federal courts, and plural federal authority all introduce institutional competition that disciplines capture.

Scope and limits: The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium is a positive theory about incentive equilibrium, not a claim that every agency decision is captured. The paper predicts directional tendencies and mode recurrence under specified structural conditions. Not all enforcement failures reflect capture; some reflect resource constraints, legal ambiguity, or good-faith error. The falsifiable predictions in Section VII state what outcomes would force revision of the framework.

Structure: Sections I–II lay out the Stigler mechanism and position the Enforcement Capture Equilibrium within the Chicago tradition. Sections III–IV document how capture operates in federal enforcement and at the congressional/executive design level. Sections V–VI demonstrate capture’s bipartisan pattern and present institutional competition as the structural solution. Section VII states falsifiable predictions.

Design Principles for Capture-Resistant Enforcement

The flagship article develops Stigler’s framework in detail and applies it to contemporary federal enforcement. Two companion installments examine specific domains: Installment I covers the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission; Installment II covers Commerce and the Patent Office.

Methodological Note: Cognitive Digital Twin Foresight Simulation

The paper is not a narrative critique of regulatory capture. It is the output of a Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) foresight simulation developed by MindCast AI.

A Cognitive Digital Twin reconstructs institutional behavior by modeling incentive structures, information flows, jurisdictional geometry, and decision constraints faced by real-world actors. Rather than predicting outcomes from stated intent or ideology, the simulation evaluates how institutions behave under specified structural conditions and how those behaviors persist or change across leadership cycles.

The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium described in this paper emerges from repeated CDT simulations of federal enforcement institutions under varying structural configurations. Metrics referenced throughout—Degree of Capture (DoC), Grammar Persistence Index (GPI), and Update Elasticity (UE)—are comparative outputs of these simulations, used to evaluate whether institutional structure or leadership intent dominates observed outcomes.

Falsifiable predictions in Section VII reflect forward projections of these Cognitive Digital Twin simulations under alternative structural scenarios, including fragmentation of enforcement authority, transparency mandates, and state substitution dynamics.

The methodology does not assume capture. It tests whether capture emerges as an equilibrium under specified conditions—and whether altering enforcement structure disrupts that equilibrium.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. See relevant work:

Chicago School Accelerated—The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics (Dec 2025) Establishes the theoretical foundation for integrating Stigler's capture framework with behavioral economics insights, providing the analytical vocabulary that the present paper applies to enforcement structure.

Federal Political Market Failure and State Substitution as a Free-Market Corrective (Jan 2026) Develops the comparative institutional case for state enforcement as a Stiglerian response to federal capture, demonstrating why concurrent jurisdiction produces race-to-top dynamics rather than regulatory arbitrage.

How Trump Administration Political Access Displaced Antitrust Enforcement—and Why States Should Now Step In (Jan 2026) Documents authority routing in merger review during 2017-2021, quantifying the Grammar Persistence Index and Update Elasticity metrics applied throughout the present paper.

The Crypto ATM Regulatory Convergence (Jan 2026) Traces rulemaking deferral at the federal level and state substitution responses, providing the empirical basis for predictions about state consumer protection expansion in Section VII.

From Open Market to Private Governance, Coordination Capture in the Compass–Anywhere Merger (Dec 2025) Analyzes evaporating remedies and behavioral conditions in a contemporary merger clearance, illustrating the temporal arbitrage and remedy design modes described in Section III.

I. What Free Markets Actually Require

Free market rhetoric often treats enforcement as distortion rather than infrastructure. Surface-level advocates deploy “free market” as an argument against any enforcement action, claiming regulation distorts markets, enforcement interferes with voluntary exchange, and government should stand aside and let markets clear. The position sounds like Chicago School economics but misreads Chicago School economics fundamentally.

Myth vs. Reality: Stigler and Federal Enforcement

Myth: “Stigler showed regulation fails, so federal enforcement is hopeless.” Reality: Stigler showed monopoly enforcement is structurally prone to capture; that points toward federal design choices (fragmentation, transparency, cross-level competition), not withdrawal. The Stiglerian response to captured federal enforcement is not less enforcement—it is enforcement structured to resist capture.

A. Freedom From Private Coercion

Free markets are not defined by the absence of government. Free markets are defined by the presence of voluntary exchange. The “free” in free market refers to freedom from coercion—including private coercion.

A cartel that fixes prices coerces buyers. A monopolist that excludes competitors coerces the excluded. A dominant platform that controls access coerces participants who have no alternative. A fraudster who exploits information asymmetry coerces victims who cannot protect themselves. These are not market outcomes. These are market failures that look like market outcomes because the coercion is private rather than governmental.

Milton Friedman understood the distinction. Capitalism and Freedom (1962) identifies government’s role in maintaining “a framework of law” as essential to competitive markets. The framework includes enforcement against private coercion. Markets without such enforcement are not free—they are arenas where private power substitutes for price competition.

B. Enforcement as Market Infrastructure

Enforcement is not external to markets. Enforcement is infrastructure that markets require.

Property rights require enforcement. Contracts require enforcement. Competition requires enforcement against collusion, exclusion, and fraud. Without enforcement, the strongest party prevails regardless of efficiency. That outcome is predation wearing market form.

Ronald Coase’s The Problem of Social Cost (1960) established the framework for thinking about enforcement. In a world without transaction costs, private bargaining resolves all coordination problems regardless of legal rules. In the real world, transaction costs are pervasive. Legal rules—including enforcement—reduce transaction costs that would otherwise prevent efficient exchange.

The question Coase asked was not “should there be enforcement?” The question was “which enforcement institution handles coordination problems at lowest cost?” Comparative institutional analysis asks which institution—courts, agencies, states, private parties—supplies enforcement most efficiently. Comparative institutional analysis does not ask whether enforcement should exist.

Enforcement is market infrastructure because it lowers the transaction costs that otherwise let private power substitute for exchange.

C. Stigler’s Contribution: When Enforcement Fails

Stigler asked why enforcement infrastructure fails even when regulators act in good faith.

The standard assumption before Stigler was that regulatory failure reflected incompetence, underfunding, or corruption. Fix the personnel, increase the budget, prosecute the bad actors—and enforcement would serve the public interest.

Stigler rejected that assumption. Stigler showed that enforcement failure could be the equilibrium outcome of rational behavior by all parties. Agencies staffed by competent, well-funded, ethical regulators would still exhibit capture if the structural conditions produced capture as the rational outcome.

The structural conditions are:

Effective monopoly enforcement: A single decisive chokepoint controls outcome

Concentrated benefits: Identifiable parties gain substantially from favorable enforcement

Diffuse costs: Many parties each lose a little from unfavorable enforcement

Asymmetric organization: Concentrated beneficiaries can organize; diffuse victims cannot

When these conditions hold, capture is not a bug. Capture is the predicted equilibrium. Agencies will favor concentrated beneficiaries regardless of stated mission, regardless of leadership intent, regardless of formal procedures. The incentive structure dominates.

D. The Implication for Free Markets

Stigler’s framework implies that “free markets” cannot mean “no enforcement.” If enforcement is absent or captured, markets are not free—concentrated actors exercise coercive power that competitive markets are supposed to prevent.

“Free markets” must mean “enforcement structured to resist capture.” Plural enforcement venues, institutional competition, and diffuse authority make capture investment expensive and uncertain.

Surface-level advocates who oppose all enforcement in the name of free markets have the relationship backwards. Captured enforcement and absent enforcement produce the same market outcome: private coercion displaces voluntary exchange. The market-preserving response is not less enforcement. The market-preserving response is enforcement structured to resist capture.

Free markets require enforcement against private coercion, and enforcement that has been captured does not supply that function. Stigler’s contribution was identifying when capture occurs—and implying when it does not. The distinction between coercion-free exchange and coercion-enabled extraction depends on enforcement structure, not enforcement absence.

II. Stigler’s Mechanism and the Chicago Tradition

Stigler’s The Theory of Economic Regulation (1971) is frequently cited and rarely understood. Summaries reduce it to “industry captures regulators.” The mechanism is more precise and more powerful. Understanding the mechanism requires examining the investment calculus that produces capture, the organizational asymmetry that sustains it, and the information dynamics that entrench it.

A. The Investment Calculus

Stigler began with a simple observation: regulation confers valuable benefits. Entry barriers, price floors, subsidy allocations, enforcement discretion—these are worth money. Valuable things attract investment.

Industries invest in securing favorable regulation because the returns justify the cost. A merger clearance worth $500 million in synergies justifies substantial investment in securing clearance. A patent worth $1 billion in licensing revenue justifies substantial investment in favorable examination. An export license worth $200 million in sales justifies substantial investment in approval.

The investment takes predictable forms: lobbying (direct engagement with decision-makers), campaign contributions (indirect influence on political oversight), revolving door employment (regulators who anticipate industry employment decide accordingly), information control (agencies depend on regulated parties for data and expertise), litigation capacity (ability to challenge unfavorable decisions imposes costs on agencies), and regulatory complexity (complex rules favor parties with compliance infrastructure).

Stigler did not moralize about these investments. Stigler noted they were rational. A firm that fails to invest in regulatory outcomes while competitors invest is a firm that accepts competitive disadvantage. Investment in capture is not corruption—it is rational response to incentive structure.

Capture intensity should scale with expected private surplus (deal value, licensing rents, subsidy size) and fall when enforcement authority fragments across venues. The relationship is testable—and it is the lever that institutional competition pulls.

B. The Organizational Asymmetry

Regulatory costs fall on diffuse populations while regulatory benefits accrue to concentrated actors. Consumers paying higher prices due to anticompetitive mergers, workers facing suppressed wages due to labor market concentration, innovators blocked by patent thickets, communities bearing pollution that export policy permits—all bear diffuse costs.

Each individual harm is small. A merger that raises prices 3% costs each consumer a few dollars per year. No individual consumer has sufficient stake to justify organizing opposition. The collective harm may be billions of dollars, but the collective cannot organize because each individual’s share is negligible.

Mancur Olson formalized the asymmetry in The Logic of Collective Action (1965): diffuse interests face collective action problems that concentrated interests do not. Ten firms sharing $500 million in merger benefits can coordinate. Ten million consumers sharing $500 million in merger costs cannot.

The asymmetry is structural, not contingent. It does not depend on consumers being ignorant or firms being malicious. It depends on the mathematics of organization costs relative to individual stakes.

C. Visualizing the Asymmetry

The investment calculus becomes vivid when quantified:

Concentrated beneficiary: A merger worth $500 million in synergies. Ten executives and board members make the decision to invest in securing approval. Each decision-maker’s stake: $50 million. Lobbying budget justified: $10-50 million. Number of regulators to influence: perhaps 20 key staff and commissioners.

Diffuse victims: Ten million consumers who will pay 3% higher prices. Per-capita annual harm: $15. Total collective harm: $150 million annually. Cost to organize even 1% of affected consumers: exceeds the benefit any individual would receive. Number of people who would need to coordinate: 100,000 minimum for political salience.

The arithmetic is decisive. The concentrated beneficiary can spend $30 million to secure $500 million in value—a 16x return. The diffuse victim cannot spend $20 to prevent $15 in annual harm. Even if every consumer understood the stakes perfectly, rational self-interest would prevent organization.

Capture is equilibrium, not exception, because the math does not change with better regulators, clearer rules, or more transparent processes. The math changes only when structural conditions shift—when enforcement fragments across venues and capture investment must multiply accordingly.

D. The Information Dynamic

Agencies need information to regulate, and that information comes predominantly from regulated parties. Regulated parties have the data. They have the expertise. They have the resources to compile, analyze, and present. Diffuse victims have none of these.

A merger review receives detailed economic analysis from the merging parties and their expert witnesses. Consumer groups, if they participate at all, submit generalized concerns without deal-specific data. The informational asymmetry shapes what agencies know and therefore what agencies decide.

Over time, agencies come to see the world through the lens of parties who provide information. Career staff develop expertise by working on matters where industry provides the analytical framework. The “reasonable” range of policy options becomes the range that sophisticated repeat players have defined.

Information dependence is not conspiracy. Agencies do not intend to favor regulated parties. Agencies favor regulated parties because regulated parties are the primary source of decision-relevant information.

E. Equilibrium, Not Exception

The critical Stiglerian insight is that capture is the equilibrium outcome of these dynamics. Given a single decisive chokepoint, concentrated benefits, diffuse costs, and organizational asymmetry, rational behavior by all parties produces capture.

Regulators are not corrupt. Regulators respond to the information they receive, the parties who engage them, and the career incentives they face. Industry is not malicious. Industry invests in favorable outcomes because the returns justify the cost. Consumers are not ignorant. Consumers do not organize because individual stakes do not justify organization costs.

Everyone behaves rationally. The outcome is capture. Changing personnel does not change the outcome because personnel change does not change the incentive structure. New regulators face the same information asymmetry, the same engagement asymmetry, the same career incentives.

The equilibrium holds until structural conditions change.

F. What Changes the Equilibrium

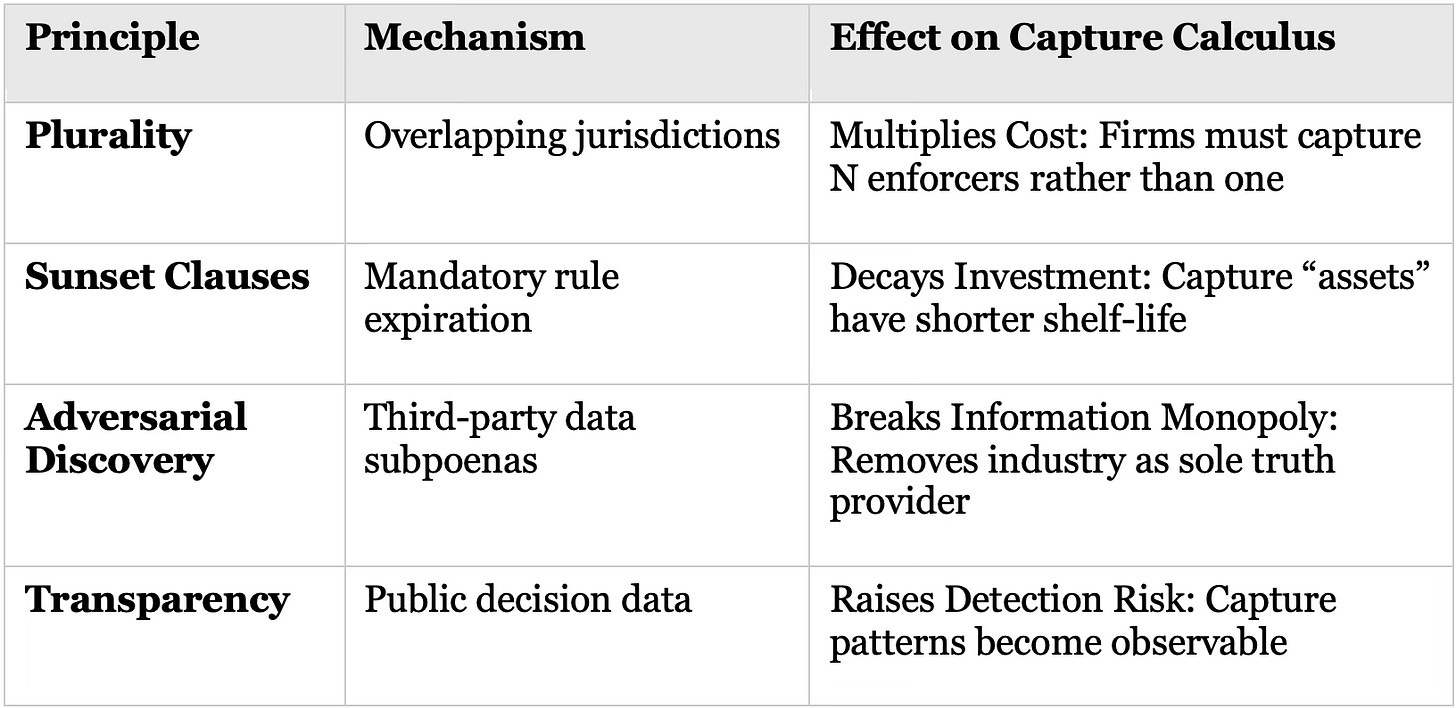

Stigler’s framework implies that capture can be broken by altering structural conditions:

Break the chokepoint: Multiple enforcement venues mean capture investment must target all venues. The cost rises; the certainty falls.

Reduce benefit concentration: Smaller stakes mean less capture investment justifies. Structural separation reduces concentration.

Organize diffuse interests: Consumer groups, state attorneys general, and private enforcement reduce organizational asymmetry.

Alter information dynamics: Transparency requirements, independent data sources, and adversarial processes reduce information dependence.

Change career incentives: Revolving-door restrictions and alternative career paths reduce industry alignment.

None of these solutions involves “better regulators.” All involve structural change to the conditions that produce capture.

G. Bootleggers and Baptists: How the Coalition Forms

Bruce Yandle’s “Bootleggers and Baptists” model (1983) explains how capture coalitions form and sustain themselves. The model takes its name from Sunday closing laws: Baptists supported them on moral grounds; bootleggers supported them because closed liquor stores meant more customers. Neither group acknowledged the other, but both lobbied for the same outcome.

The pattern is general. Every successful capture coalition includes:

Baptists: Parties who provide public-interest justification. They speak the language of consumer protection, safety, innovation, or market integrity. Their arguments are sincere. Their presence legitimizes the regulatory outcome.

Bootleggers: Parties who capture the economic rents. They fund the lobbying. They provide the technical expertise. They write the rule language. Their interests are served by the outcome the Baptists justify.

The coalition works because neither party needs to coordinate explicitly. Baptists do not know they are providing cover. Bootleggers do not advertise their rent-seeking. The regulator sees broad support—moral voices and technical experts aligned—and concludes the outcome serves the public interest.

Illustration: Occupational licensing. Consumer safety advocates (Baptists) support licensing requirements to protect the public from unqualified practitioners. Incumbent practitioners (Bootleggers) support licensing requirements to reduce competition and raise prices. The regulator sees both groups supporting the same rule and concludes licensing serves the public. The outcome: higher prices, reduced access, and incumbent protection—wearing the aesthetic of consumer safety.

The Bootleggers-and-Baptists dynamic explains why information arbitrage is so effective. Industry does not present its arguments as rent-seeking. Industry presents its arguments through Baptist proxies or in Baptist language. The information that reaches the regulator has already been filtered through a legitimizing frame.

H. Stigler and the Chicago Theory of Government

Positioning the Enforcement Capture Equilibrium relative to the Chicago tradition requires understanding what is “Stigler” versus what is “post-Stigler Chicago” versus what is the extension developed in the present paper.

Stigler’s original claim (1971): Regulation is “acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.” One-sided producer dominance. Industries demand regulation; politicians supply it; consumers lose. The mechanism is demand-side: industries invest because the returns justify the cost.

Peltzman’s generalization (1976): Regulators maximize political support by balancing producer and consumer interests. Pure producer capture is not equilibrium because alienating consumers has political costs. Outcomes reflect a rent-allocation compromise where both groups get something, though producers typically get more due to organizational advantages. A multi-interest model.

Becker’s extension (1983): Pressure groups compete for political influence, and deadweight losses discipline inefficient transfers. Groups that seek highly inefficient regulations face countervailing pressure from groups bearing the deadweight costs. Competition among groups constrains the worst outcomes—sometimes.

The present paper’s extension—the Enforcement Capture Equilibrium: The Stigler/Peltzman/Becker logic applies not to price-and-entry regulation but to enforcement design. The insight is that enforcement structure is itself a policy variable subject to the same capture dynamics. Concentrated beneficiaries invest not just in favorable rules but in favorable enforcement institutions: jurisdictional monopolies, long timelines, behavioral remedies, rulemaking deferrals. The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium is a MindCast AI generalization of Stigler’s mechanism from regulatory content to regulatory structure.

The generalization matters because it shifts the policy lever. Stigler implied that regulation is hopeless. Peltzman and Becker implied that regulation reflects political equilibrium and can be improved at the margin. The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium implies that enforcement structure can be designed to resist capture—that institutional competition is an engineering specification, not just a political accident.

The metrics introduced in the present paper—Grammar Persistence Index, Update Elasticity, and Degree of Capture—are MindCast AI constructs that operationalize the Stigler/Peltzman logic for enforcement institutions. They are not in the original literature. They are tools for measuring whether institutional structure dominates leadership intent (Stigler’s prediction) or whether leadership can alter outcomes within a given structure (the counter-hypothesis the framework tests).

Methodology note: Grammar Persistence Index, Update Elasticity, and Degree of Capture are scoring metrics developed by MindCast AI to operationalize Stigler/Peltzman logic for enforcement. Grammar Persistence Index = (Variance in decision outcomes across leadership changes) / (Variance in stated priorities across leadership changes); values approaching 1.0 indicate institutional behavior invariant to leadership intent. Update Elasticity measures leadership capacity to alter information flows, timelines, and remedy forms within one enforcement cycle; low Update Elasticity indicates grammar dominates. Degree of Capture estimates the degree to which agency outputs track concentrated-beneficiary preferences versus diffuse-victim preferences, calibrated using enforcement action rates, timeline distributions, remedy durability, and outcome alignment with pre-decision industry positions. These metrics are comparative and directional, not claims of ground-truth measurement; their value lies in ranking institutional susceptibility, not producing absolute scores. Probability ranges in the paper reflect simulation distributions, not point estimates.

I. The Stigler-Olson-Coase Synthesis

Three frameworks converge on a single design constraint.

Stigler explains why concentrated beneficiaries invest in capture: the returns justify the cost. Olson explains why diffuse victims do not organize resistance: individual stakes do not justify organization costs. Coase explains why enforcement institutions matter: transaction costs block the private bargaining that would otherwise resolve coordination failures.

Together they imply: enforcement must compete, or it will be purchased. Enforcement routed through a single decisive chokepoint facing concentrated beneficiaries and diffuse victims will produce capture because the investment calculus favors capture and nothing structural prevents it. Plural enforcement raises the cost of capture and lowers the certainty of return. The design constraint is institutional competition.

Stigler’s mechanism is precise: concentrated benefits, diffuse costs, organizational asymmetry, and information dependence produce capture. Post-Stigler Chicago (Peltzman, Becker) generalized the mechanism to multi-interest competition. The Enforcement Capture Equilibrium extends the mechanism from regulatory content to enforcement structure. Capture is not corruption; capture is the equilibrium outcome of structural conditions. The policy implication: enforcement institutions can be designed to resist capture through structural competition, and fighting capture with ethics training or personnel changes misunderstands the mechanism.

III. Modes of Capture in Federal Enforcement

Stigler’s framework predicts capture under specified structural conditions, and contemporary federal enforcement meets those conditions. Capture operates not through isolated instances but through stable modes that appear across federal agencies. Each mode described below represents a pattern where incentives, information, and timing tilt toward concentrated beneficiaries. In every case, the outcome has market aesthetic—it looks like a market outcome—but lacks market function—it does not reflect voluntary exchange free from coercion.

A. Temporal Arbitrage

Captured enforcement delays, and delay allows beneficiaries to consolidate gains before review concludes.

The mode appears across federal agencies. Merger review extends until parties have integrated operations, making divestiture costly. Consumer protection rulemaking stretches across years while harm accumulates. Patent examination continues through endless continuations while competitors are excluded. Export license decisions pend while applicants find alternative transaction structures.

Delay is not neutral. Delay favors parties who benefit from the status quo. In merger review, the status quo post-announcement is deal momentum. In consumer protection, the status quo is continued extraction. In patent examination, the status quo is continued exclusion.

Temporal arbitrage is difficult to challenge because delay always has justification. Agencies need time for careful analysis. Complex matters require extended review. Resource constraints limit processing speed. Each justification is plausible. The pattern—systematic delay favoring concentrated beneficiaries—is the evidence of capture.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The delay looks like careful deliberation (aesthetic). The delay functions as permission for incumbents to consolidate advantage (function). The aesthetic is regulatory prudence. The function is regulatory permission.

B. Information Arbitrage

Captured enforcement privileges information from regulated parties.

The mode is pervasive across federal enforcement. Merger review depends on documents and data from merging parties. Consumer protection depends on industry data about practices and harms. Patent examination depends on applicant disclosure and prior art searches that applicants shape. Export control depends on license applicants describing their own end uses.

Information arbitrage operates through selective disclosure, framing, and expertise. Regulated parties disclose information that supports their position. They frame issues in terms favorable to their interests. They supply the experts who define what “reasonable” analysis looks like.

Diffuse interests cannot match the information provision. Consumer groups lack merger-specific data. Individual fraud victims cannot aggregate their experiences into enforcement-relevant patterns. Small innovators cannot document the patent thicket blocking their entry.

Information arbitrage intersects with the Bootleggers-and-Baptists dynamic. Industry does not present raw self-interest to regulators. Industry presents analysis framed in public-interest language, supported by credentialed experts, echoed by trade associations with anodyne names. The Baptist vocabulary makes the Bootlegger data palatable.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The agency appears to make evidence-based decisions (aesthetic). The evidence base is controlled by parties with stakes in the outcome (function). The aesthetic is technocratic competence. The function is laundered advocacy.

C. The Revolving Door and Cultural Capture

Captured enforcement exhibits personnel flow between agency and regulated industry, but the revolving door is only the visible mechanism. Beneath it lies a deeper phenomenon: cultural capture.

Career-incentive capture operates through explicit expectations. Regulators who anticipate industry employment after government service face implicit incentives not to antagonize future employers. The incentive need not be conscious. Career planning shapes what feels like reasonable enforcement.

Cultural capture operates through shared worldview. Even without job offers pending, regulators may rule in favor of industry because they want to be seen as “sophisticated,” “pro-innovation,” or “serious” by the people whose opinions they value. When regulators and regulated share social circles, conferences, vocabulary, and prestige markers, the regulator’s sense of what is “reasonable” converges with the regulated party’s preferences.

Cultural capture is harder to detect than revolving-door capture because it leaves no paper trail. No job offer. No explicit quid pro quo. Just a gradual alignment of perspective between people who read the same journals, attend the same conferences, and seek approval from the same peer group.

Template: A regulator who wants to be seen as “understanding the industry” by sophisticated practitioners will internalize a bias toward permissive enforcement—not because of a job offer, but because skepticism would mark them as unsophisticated in the eyes of people whose respect they seek. The pattern appears in financial regulation, technology oversight, pharmaceutical review, and any domain where a prestige hierarchy exists between regulators and regulated. The capture is real. The mechanism is social, not financial.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The regulator appears to bring expertise and nuance (aesthetic). The expertise comes packaged with industry-aligned priors (function). The aesthetic is insider knowledge. The function is insider bias.

D. Regulatory Complexity

Captured enforcement produces complex rules that favor parties with compliance infrastructure.

Complexity is not inherently captured. Some domains are genuinely complex. But complexity has distributional effects. Parties with legal departments, compliance teams, and specialized counsel navigate complexity efficiently. Parties without these resources face disproportionate costs. Complexity signals capture only when complexity rises while enforcement efficacy and observability fall.

Captured complexity appears when rules grow elaborate without corresponding gains in regulatory effectiveness. Comment processes produce rules responsive to the most sophisticated commenters. Exceptions and safe harbors multiply to address concerns raised by parties with resources to raise concerns. The resulting complexity is defensible provision by provision. The aggregate effect is to advantage repeat players.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The rules appear comprehensive and carefully tailored (aesthetic). The rules function as barriers to entry for unsophisticated parties (function). The aesthetic is thoroughness. The function is exclusion.

E. Rulemaking Deferral

Captured enforcement defers concrete protection to future rulemaking.

The mode is especially visible at the Federal Trade Commission. Enforcement authority exists. Specific protection does not. The gap is filled by rulemaking proceedings that extend across years, produce frameworks without binding requirements, and defer concrete obligations to subsequent proceedings.

Deferral serves capture because deferral is delay with procedural legitimacy. Each rulemaking stage is defensible. Notice-and-comment is required. Economic analysis takes time. Stakeholder input is valuable. The aggregate effect is protection deferred indefinitely while harm accumulates.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The agency appears to be developing careful, well-considered rules (aesthetic). The rulemaking functions as indefinite permission for harmful conduct (function). The aesthetic is deliberation. The function is deferral with distributional consequences.

F. Remedies That Evaporate

Captured enforcement produces remedies that appear meaningful and prove ineffective.

Behavioral remedies in merger review are the canonical form. Agencies clear transactions subject to conditions: firewalls, licensing requirements, non-discrimination obligations. The conditions address concerns on paper. The conditions prove unenforceable in practice.

The mode reflects information asymmetry in remedy design and enforcement. Agencies depend on parties’ representations about remedy feasibility. Post-merger monitoring is resource-constrained. Remedy violations are difficult to detect and costly to prosecute.

Market aesthetic vs. market function: The merger clearance appears conditional and carefully monitored (aesthetic). The conditions evaporate into the market structure they nominally prevented (function). The aesthetic is regulatory oversight. The function is regulatory theater.

What Non-Captured Enforcement Looks Like

Non-captured enforcement has a different signature: short feedback loops that surface harm before lock-in, adversarial information supply that breaks dependence on regulated parties, remedies that bind because they are structural rather than behavioral, and timelines that do not allow incumbents to consolidate advantage before review concludes.

Capture flips each of these properties. Feedback loops lengthen. Information supply becomes monopolized. Remedies become behavioral and therefore evaporable. Timelines extend until advantage is locked in. Recognizing capture requires recognizing which properties have flipped.

Capture operates through modes, not just instances. Temporal arbitrage, information arbitrage, cultural capture, regulatory complexity, rulemaking deferral, and evaporating remedies appear across federal agencies because the structural conditions producing them are consistent. Each mode produces outcomes with market aesthetic but without market function. Identifying capture requires pattern recognition: any individual delay, complexity, or deferral has justification, but the pattern—systematic benefit to concentrated interests across modes—is the evidence.

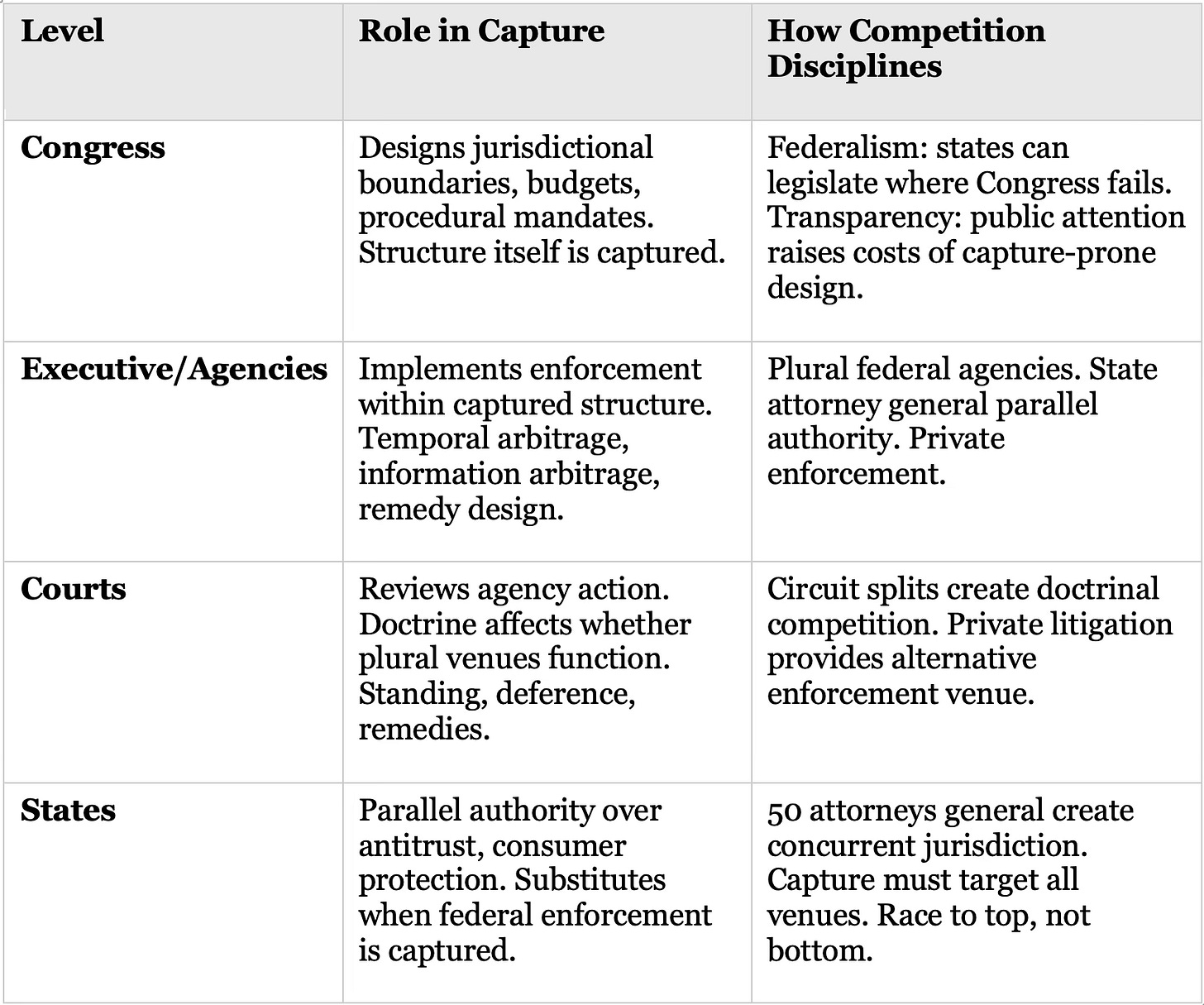

IV. Congress, the White House, and the Production of Enforcement Structure

The preceding section analyzed capture at the agency level. But agencies operate within structures that Congress and the White House design. Jurisdictional grants, budgets, procedural mandates, and appointment processes are themselves products of organized interests. Capture operates not just at enforcement implementation but at enforcement design.

A. The Supply Side of Enforcement Structure

Stigler’s original model focused on demand: industries demand favorable regulation because benefits exceed costs. Peltzman added supply: politicians supply regulation to maximize political support. The full model has both demand and supply.

Apply the model to enforcement structure. Industries demand enforcement structures that favor capture: monopoly jurisdiction, long timelines, behavioral remedies, underfunded agencies, complex procedures. Politicians supply those structures in exchange for political support.

The result: enforcement structure is endogenous to the same capture dynamics that produce captured enforcement. The structure that produces capture is not an accident. It is an equilibrium.

B. Congressional Production of Capture-Prone Structure

Congress controls the structural parameters that determine capture probability:

Jurisdictional grants: Congress decides which agency has authority over which conduct. Concentrated jurisdictions (one agency controls) favor capture. Diffuse jurisdictions (multiple agencies share authority) resist capture. Jurisdictional design is a policy choice, not a technical necessity.

Budget allocations: Underfunded agencies cannot challenge well-resourced parties. Enforcement capacity is a budget line. Congress can starve agencies of resources while nominal authority remains intact. The result: legal authority without practical capacity.

Procedural mandates: Requirements for notice-and-comment, economic analysis, Office of Management and Budget review, and judicial review all extend timelines and raise costs. Each requirement is defensible individually. The aggregate effect is temporal arbitrage structurally mandated.

Appointment processes: Senate confirmation for agency leadership creates veto points where organized interests can block appointments. Vacancies persist. Acting officials lack authority. Leadership instability compounds institutional grammar.

These are not failures of congressional intent. These are equilibrium outcomes of the same Stigler mechanism operating on Congress. Concentrated beneficiaries invest in structural design. Diffuse victims do not organize around jurisdictional boundaries or budget allocations. Congress responds to the organized.

C. Executive Branch Production of Capture-Prone Structure

The White House controls enforcement through:

Appointments: The President selects agency heads. Selection criteria include industry relationships, prior positions, and political alignment. Appointees arrive with frameworks shaped by prior experience. The revolving door begins before appointment.

Executive orders: Presidential directives shape enforcement priorities, cost-benefit requirements, and interagency coordination. Orders can accelerate or impede enforcement across the executive branch.

Office of Management and Budget review: The Office reviews significant rules. Review adds timeline. Timeline favors status quo. The Office becomes a structural contributor to temporal arbitrage.

Interagency coordination: When multiple agencies share jurisdiction, White House coordination can discipline agencies toward unified policy—or can add veto points where any agency can block action. Coordination is structure.

D. The Federal Architecture of Capture

Capture is not just an agency phenomenon. Capture is an equilibrium over the full federal architecture:

The table shows that capture-resistant enforcement requires attention to all levels. Reforming agency practice while leaving congressional structure intact addresses symptoms, not causes. Institutional competition must operate across the full architecture.

Capture operates at the design level, not just the implementation level. Congress produces jurisdictional grants, budgets, and procedural mandates that are themselves subject to capture dynamics. The White House produces appointments, executive orders, and coordination mechanisms that shape enforcement structure. Reforming agencies without reforming the structure that produces captured agencies is treating symptoms. The federal architecture must be understood as an integrated system where capture dynamics operate at every level, and capture-resistant enforcement requires structural intervention across Congress, the executive branch, courts, and states.

V. Bipartisan Federal Enforcement Patterns

If capture were ideological, it would appear under one party and not the other. Capture appears under both parties because capture is structural. The beneficiaries of capture shift across administrations; the mechanism does not.

A. Capture Across Administrations

Department of Justice Antitrust Division: The Obama administration cleared Ticketmaster-Live Nation (2010) with behavioral remedies that failed to constrain market power now subject to renewed enforcement. The Trump administration cleared transactions over career staff objection. Different beneficiaries; same temporal arbitrage and evaporating remedies.

Federal Trade Commission Consumer Protection: The Biden administration deferred crypto-ATM rulemaking while losses mounted. The Trump administration reduced enforcement actions across consumer protection categories. Different rhetoric; same rulemaking deferral and enforcement deprioritization.

Commerce Export Control: The Obama administration settled with ZTE, then reversed sanctions under industry pressure. The Trump administration issued Huawei restrictions, then granted license exceptions under industry pressure. Different targets; same access-based routing.

Patent and Trademark Office Examination: Patent quality concerns have persisted across decades and administrations. Examination time pressure, continuation practice, and allowance rates show no partisan pattern. The structural conditions are invariant.

B. Why Personnel Changes Do Not Help

MindCast AI’s Installed Cognitive Grammar framework measures whether an institution’s behavior survives leadership turnover because procedures, information sources, and career incentives reproduce the same decision shape regardless of who occupies leadership positions.

Agencies exhibit high Grammar Persistence Index (0.84) and low Update Elasticity (0.22). Grammar Persistence Index rises when procedures, information sources, and career incentives remain stable across leadership changes; Update Elasticity rises when leadership can re-route information, timelines, and remedy form within one enforcement cycle.

New leadership inherits staff whose professional formation occurred under prior capture conditions, procedures designed by and for repeat players, information sources that remain industry-dominated, resource constraints that force prioritization favoring sophisticated parties, and pending matters with momentum that new leadership cannot easily reverse.

Leadership intent runs into institutional grammar. A new Federal Trade Commission chair who wants to prioritize diffuse consumer harm faces an agency structured around matters with organized complainants. A new Department of Justice Assistant Attorney General who wants to challenge mergers faces review timelines that sophisticated parties have learned to exploit.

The grammar is not conspiracy. The grammar is accumulated institutional practice optimized for the parties who engage most intensively. Changing the grammar requires sustained structural intervention, not announcement of new priorities.

C. The Consistency Is the Evidence

Stigler’s framework generates a testable prediction: capture will appear consistently across administrations where structural conditions hold.

The prediction holds. The Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, Commerce, and the Patent and Trademark Office all exhibit capture patterns under both Democratic and Republican leadership. The beneficiaries rotate. The modes persist.

Consistency distinguishes Stiglerian explanation from partisan explanation. Partisan accounts predict capture under the disfavored party and effectiveness under the favored party. The evidence shows capture under both. The structural explanation fits; the partisan explanation does not.

Capture is bipartisan because capture is structural. The mechanism does not care about party affiliation. Administrations that inherit a single decisive chokepoint facing concentrated beneficiaries will exhibit capture regardless of leadership intent. Partisans who blame the other party for regulatory failure misidentify the cause: both parties preside over capture because both parties inherit structural conditions that produce it. Electoral change does not produce structural change.

VI. Institutional Competition as the Market-Preserving Response

Stigler’s framework implies a solution. If a single decisive chokepoint produces capture, plural enforcement resists capture. Institutional competition is not anti-market. Institutional competition is the structural condition under which enforcement serves market function. The principles below are not ideological preferences; they are engineering specifications derived from Stigler’s diagnosis.

A. Why Institutional Competition Works

Capture investment targets enforcement decision-makers. When one chokepoint controls enforcement outcome, capture investment has a single target. When multiple institutions share authority, capture investment must target all institutions simultaneously.

The economics shift. Capturing one agency costs X and delivers certain benefit. Capturing three agencies costs 3X and delivers uncertain benefit—any uncaptured agency can enforce. Rational capture investment declines as enforcement venues multiply.

Plural enforcement also introduces competitive dynamics. Agencies that fail to enforce face criticism that agencies enforcing in parallel do not. Reputational competition and bureaucratic competition motivate enforcement that monopoly agencies lack incentive to pursue.

Institutional competition breaks capture by lowering the expected return on political investment relative to competitive investment. When capture is expensive and uncertain, firms rationally redirect resources toward competitive performance. That is the market-preserving effect.

B. The Race-to-the-Bottom Objection—and Why It Fails

The standard critique of institutional competition is the “race to the bottom.” If multiple jurisdictions have authority, firms will forum-shop for the most lenient enforcer. Competition among enforcers will produce progressively weaker enforcement as each jurisdiction tries to attract business by reducing regulatory burden.

The objection is serious. The objection is also inapplicable to the structure the present paper recommends.

The race to the bottom occurs under exclusive jurisdiction: When a firm can choose which single enforcer will have authority, the firm chooses the most lenient. Each jurisdiction, wanting to attract firms (and fees, and jobs), weakens enforcement. The result is regulatory arbitrage—firms incorporate in Delaware, register ships in Panama, domicile intellectual property in Ireland.

The race to the top occurs under concurrent jurisdiction: When multiple enforcers can all act simultaneously, the firm must satisfy the strictest one. If five state attorneys general can sue, the firm cannot escape by satisfying only the most lenient. The firm faces the union of constraints, not the intersection. Concurrent jurisdiction creates a race to the top because the binding constraint is the strictest enforcer, not the most lenient.

State attorneys general exercising parallel antitrust and consumer protection authority is concurrent jurisdiction. The firm cannot choose which attorney general will have authority. All fifty have authority simultaneously. Capturing the federal agency does not disable state enforcement—it triggers state enforcement.

The distinction is crucial to the Stiglerian design. The paper does not recommend letting firms choose among enforcers. The paper recommends letting enforcers compete to act. The firm faces more enforcement risk, not less. Capture investment becomes less attractive because capturing one venue does not neutralize the others.

C. Forms of Institutional Competition

State enforcement: Fifty state attorneys general hold parallel authority over antitrust and consumer protection. Capturing federal agencies does not disable state enforcement. In MindCast AI’s modeled comparisons across recent enforcement domains, state enforcement exhibits lower Degree of Capture (0.31) than federal enforcement (0.72) because state attorneys general face different incentive structures—accountability to local voters, proximity to diffuse victims, career paths independent of regulated industry.

Private enforcement: Antitrust and consumer protection statutes enable private lawsuits. Class actions aggregate diffuse interests that cannot otherwise organize. Private enforcement supplements public enforcement and continues when public enforcement is captured.

Market-based enforcement: When markets function properly, private actors serve enforcement functions. Short-sellers profit by identifying and publicizing fraud—they are private information processors whose financial incentives align with market integrity. Investigative journalists surface misconduct. Activist investors challenge management that extracts private benefits. These market-based enforcers provide adversarial information that captured agencies fail to develop.

Illustration: When captured agencies attack short-sellers rather than investigate the frauds short-sellers identify, capture is visible in real time. The concentrated beneficiary (the fraudster) uses the monopoly enforcer (the agency) to suppress the informational competitor (the short-seller). Market-based enforcement becomes a diagnostic: agencies that protect targets of private enforcement from private enforcers are exhibiting capture.

Plural federal authority: The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission share antitrust jurisdiction. The division introduces competition that single-agency enforcement lacks. Proposals to consolidate authority would eliminate this competition and increase capture risk.

International enforcement: Non-U.S. competition authorities review global transactions. The European Union, the United Kingdom, and other enforcers provide institutional competition that purely domestic enforcement lacks.

D. Courts as Enforcement Venue—and Constraint

Courts occupy a dual role in enforcement structure. Courts are an enforcement venue (private litigation, judicial review of agency action). Courts are also a constraint on other enforcement venues (standing requirements, standards of review, remedial limitations).

Courts as enforcement venue: Private antitrust litigation and class actions provide enforcement that continues when agencies are captured. Judicial review of agency action can reverse captured decisions. Circuit courts create doctrinal competition—forum shopping among circuits introduces plurality that national agencies lack.

Courts as constraint: Judicial doctrine affects whether nominal plurality becomes functional plurality. Standing requirements limit who can sue. Class certification barriers prevent aggregation of diffuse interests. Deference doctrines (now evolving post-Chevron) affect how closely courts scrutinize agency capture. Remedial limitations constrain what successful plaintiffs can obtain.

The implication: plural enforcement venues can coexist with functional monopoly if judicial doctrine raises the cost of using alternative venues. A firm facing fifty state attorneys general and private plaintiffs faces less enforcement risk if standing doctrine, class certification barriers, and preemption claims reduce the probability that those venues will actually act.

Live federal design questions: How courts shape institutional competition is currently contested in several domains:

• Whether federal antitrust law preempts state consumer protection claims

• Whether arbitration clauses block class aggregation of diffuse interests

• Whether standing doctrine permits competitor or consumer suits

• Whether major questions doctrine limits agency authority to act without explicit congressional authorization

Each doctrinal choice affects capture. Doctrines that raise barriers to alternative venues strengthen agency monopoly. Doctrines that lower barriers introduce the institutional competition that disciplines capture.

E. State Substitution in Action

State attorneys general have emerged as primary enforcers where federal agencies exhibit capture.

The pattern is not new. State attorneys general led tobacco litigation when federal agencies did not. State attorneys general led mortgage servicing enforcement when federal agencies lagged. State attorneys general are leading tech platform investigations alongside federal proceedings.

What is new is the systematic nature of federal capture and the corresponding systematic nature of state response. MindCast AI’s simulation identifies a Critical De-Risking Zone: the 12-24 month period following federal clearance during which state substitution probability exceeds 70%.

State enforcement is not anti-federal ideology. State enforcement is comparative institutional analysis in action. When federal enforcement imposes higher capture costs than state enforcement, enforcement migrates to states. Stigler’s framework predicts and endorses the migration.

Examples in operation: Iowa enacted crypto-ATM consumer protection ($1,000 daily cap, 15% fee limit, 90-day refund window) while federal legislation stalled. Washington introduced SB 6091 (concurrent public listing mandate) three days after federal merger clearance of Compass-Anywhere. More than 30 state attorneys general joined as co-plaintiffs in Live Nation litigation, preserving enforcement capacity independent of federal commitment.

F. Mapping Institutional Competition to Live Federal Debates

The principles of the present paper connect directly to contested federal design questions:

Consolidation proposals for the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission: Some propose merging antitrust authority into a single agency for efficiency. The Stiglerian analysis opposes consolidation: reducing enforcement venues from two to one lowers capture cost and raises capture certainty. The efficiency gains from consolidation are smaller than the capture losses from monopoly.

Federal preemption of state artificial intelligence and consumer protection regulation: Industry groups seek federal legislation that preempts state regulation. The Stiglerian analysis opposes broad preemption: preemption converts concurrent jurisdiction (race to top) into exclusive federal jurisdiction (capturable monopoly). Targeted preemption addressing genuine conflicts is different from blanket preemption that eliminates institutional competition.

Centralization of export control and industrial policy: Some propose consolidating export control, CHIPS Act implementation, and artificial intelligence policy in the Executive Office of the President. The Stiglerian analysis is cautious: consolidation may improve coordination but also creates a single capture target. Departmental competition (Commerce vs. Defense vs. State) introduces friction but also introduces the institutional competition that disciplines capture.

Arbitration and class action waivers: Mandatory arbitration with class waivers eliminates the aggregation mechanism that allows diffuse interests to organize. The Stiglerian analysis opposes blanket enforcement of such waivers in consumer and employment contexts: they disable an enforcement venue that disciplines agency capture.

G. Structural Reform Where Substitution Fails

State substitution works where states have parallel authority. States do not have parallel authority over patent examination or export control. For exclusively federal domains, Stigler’s framework implies structural reform:

Patent and Trademark Office: Introduce competing examination tracks. Allow applicants to choose rigorous examination with stronger presumption of validity or standard examination with weaker presumption. Competition disciplines quality.

Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security: Require transparency for license decisions and subsidy allocations. Publish anonymized decision data enabling pattern analysis. Reduce information asymmetry that access arbitrage exploits.

General: Shorten feedback loops. Make capture costs visible faster. Diffuse interests cannot organize around harms they cannot observe. Transparency is organizational infrastructure for diffuse interests.

These reforms are harder than state substitution because they require statutory change. But they follow from the same Stiglerian logic: structural conditions produce capture; change structural conditions to break capture.

Institutional competition is the structural response to capture. Plural enforcement makes capture investment expensive and uncertain. The race-to-the-bottom objection fails because concurrent jurisdiction creates a race to the top: the firm must satisfy the strictest enforcer, not the most lenient. State substitution provides immediately available institutional competition for antitrust and consumer protection. Courts can enable or constrain institutional competition through doctrine. For exclusively federal domains, structural reform is required. “More enforcement” is not the solution; “better enforcement” is not the solution; plural enforcement is the solution—enforcement structured so that capture of any single venue does not disable enforcement overall.

VII. Falsifiable Predictions

Stigler’s framework generates predictions, and MindCast AI’s methodology quantifies them. The following predictions are subject to falsification by observed outcomes through 2028. Predictions that cannot be falsified are not predictions.

A. Capture Persistence Predictions

Federal enforcement capture will persist absent structural change. Degree of Capture metrics will remain above 0.60 at the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Personnel changes will not alter the pattern.

Modes of capture will continue across federal agencies: temporal arbitrage in merger review, rulemaking deferral in consumer protection, information arbitrage in export control, repeat-player advantage in patent examination.

Bipartisan capture will be confirmed by enforcement patterns under future administrations. Capture is structural; party control does not alter structural conditions absent fragmentation of enforcement authority or transparency reforms enacted by Congress or through court-driven doctrine changes.

Bright-line falsifier: If federal Degree of Capture drops below 0.40 in two of the four agencies (Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission, Commerce, Patent and Trademark Office) without fragmentation of enforcement authority or transparency reforms, the diagnosis fails and the framework requires revision.

Counter-prediction (tests structural-dominant view): If aggressive federal leadership plus minor procedural tweaks (without structural fragmentation or transparency mandates) produce sustained Degree of Capture below 0.4 across two enforcement cycles (approximately 8 years), that outcome would falsify the structural-dominant view and suggest personnel quality matters more than the framework predicts.

B. Institutional Competition Predictions

State enforcement will intensify where federal capture is evident. Multistate coalitions will initiate at least three parallel investigations within 18 months of federal clearances that exhibit authority routing.

State consumer protection will expand. Crypto-ATM regulation will reach 25+ states by 2027. States without regulation will exhibit fraud concentration as activity migrates from regulated states.

State enforcement will catalyze federal response. Federal enforcement re-entry probability rises (0.35-0.55) when states develop enforcement infrastructure. State action raises the political cost of federal inaction.

C. Structural Reform Predictions

Patent and Trademark Office examination quality will not improve absent structural reform. Allowance rates, continuation practice, and examination time pressure will persist.

Export control arbitrage will continue absent transparency requirements. License decisions will track access rather than merit.

Proposed reforms will face opposition proportional to capture value at stake. Industries benefiting from capture will organize against structural change; diffuse beneficiaries of reform will not organize equivalently.

The predictions specify observable outcomes that would disconfirm the framework if they fail to appear. The counter-prediction identifies what would falsify the structural-dominant view. The test of structural analysis is whether structural conditions predict outcomes. If capture persists across administrations and institutional competition disciplines capture where it emerges, Stigler’s framework is confirmed. If outcomes diverge from predictions, the framework requires revision. Track them.

VIII. Conclusion: Structure, Not Personnel

George Stigler did not argue that regulators are corrupt. Stigler argued that enforcement routed through a single decisive chokepoint facing concentrated beneficiaries and diffuse victims produces capture as equilibrium—regardless of regulatory intent, competence, or ethics.

Fifty years of evidence confirms the prediction. Federal enforcement agencies meeting Stigler’s structural conditions exhibit capture across administrations, across domains, across decades. The consistency is the evidence.

The policy implication is direct: enforcement structure can be designed to resist capture. Institutional competition—state attorneys general, private enforcement, plural federal authority, courts as alternative venues—raises the cost of capture and lowers its certainty. Where institutional competition is available, enforcement migrates to uncaptured venues. Where institutional competition is unavailable, structural reform is required.

Stigler was Chicago. His framework supports enforcement—enforcement structured to resist capture and serve market function rather than concentrated beneficiaries. That is what free markets require.

Forthcoming Companion Installments

Installment I (Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission): Antitrust authority routing, consumer protection failure, state substitution models.

Installment II (Commerce and Patent Office): Export control arbitrage, patent system capture, structural reform options. Both installments link to MindCast AI’s detailed case publications.

References

Stigler and Chicago School Foundations

Stigler, George J. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science2, no. 1 (Spring 1971): 3–21.

Peltzman, Sam. “Toward a More General Theory of Regulation.” Journal of Law and Economics 19, no. 2 (August 1976): 211–40.

Becker, Gary S. “A Theory of Competition Among Pressure Groups for Political Influence.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 98, no. 3 (August 1983): 371–400.

Posner, Richard A. “Theories of Economic Regulation.” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 5, no. 2 (Autumn 1974): 335–58.

Bootleggers and Baptists

Yandle, Bruce. “Bootleggers and Baptists: The Education of a Regulatory Economist.” Regulation 7, no. 3 (May/June 1983): 12–16.

Public Choice and Collective Action

Buchanan, James M., and Gordon Tullock. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962.

Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Free Market Foundations

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Coase, Ronald H. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (October 1960): 1–44.

Cultural Capture

Kwak, James. “Cultural Capture and the Financial Crisis.” In Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest Influence and How to Limit It, edited by Daniel Carpenter and David Moss. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Institutional Design and Multiple Principals

Martimort, David. “The Life Cycle of Regulatory Agencies: Dynamic Capture and Transaction Costs.” Review of Economic Studies 66, no. 4 (1999): 929–947.