MCAI Lex Vision: Antitrust Without Discipline

iRobot, Microsoft-Activision, and the Cost of Evading Courts

The US FTC’s intervention in the Amazon-iRobot transaction destroyed a company without ever testing the underlying theory in court. The agency’s challenge to Microsoft-Activision, litigated to judgment, failed on the merits-and the deal closed. Same agency. Same leadership. Same speculative theories of harm. Opposite outcomes. The difference was not politics or ideology. The difference was whether courts intervened.

I. The Pattern

Two recent FTC enforcement actions reveal a structural flaw in modern antitrust: when agencies avoid adjudication, error becomes irreversible; when courts engage, error is corrected before harm hardens. The iRobot and Microsoft-Activision cases arose from the same enforcement regime, under the same leadership, using similar speculative theories. Yet only one company survived. The divergence tracks a single institutional variable-whether courts intervened-not politics, ideology, or agency preference.

Modern FTC enforcement increasingly relies on speculative, forward-looking narratives of harm while minimizing exposure to judicial review. Rather than litigate weak theories to judgment, the agency pursues deal deterrence through investigation, delay, public signaling, and coordination with foreign regulators. Such tactics reduce the cost of error for the agency while increasing the cost of error for markets. The result is enforcement without falsification-and outcomes no institution can correct.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on law and economics foresight simulations. See our Chicago School Accelerated — The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics framework.

II. What the Analysis Contributes

Antitrust scholarship has long debated the appropriate standard of proof, the role of speculation in merger review, and the tension between enforcement discretion and judicial oversight. The iRobot-Microsoft comparison sharpens these debates by isolating court engagement as the decisive variable. Three specific contributions emerge.

First, behavioral transmission speed as a missing variable. Classic antitrust assumes rational actors wait for litigation outcomes before adjusting behavior. Behavioral economics demonstrates that market participants respond to regulatory signals immediately-repricing risk, withdrawing capital, and triggering exit cascades before any court can evaluate the underlying theory.

Second, court avoidance as a systemic failure mode. The iRobot and Microsoft-Activision contrast cannot be explained by ideology or leadership. Both cases arose from the same regime using similar theories. The divergence tracks whether courts intervened. Court avoidance constitutes a structural design flaw that prevents institutional learning.

Third, a predictive, falsifiable framework. Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics generates forward-looking predictions with explicit measurement thresholds. If predictions fail, the framework weakens. If they hold, the framework demonstrates prospective diagnostic capacity that most antitrust analysis lacks. The framework’s structure follows.

III. The Framework: Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics

Court engagement determines whether speculative enforcement error becomes reversible or irreversible. Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics explains this mechanism by extending the classic Chicago School with behavioral economics. Three pillars anchor the framework: coordination economics (Coase: markets fail when coordination architecture degrades), incentive response (Becker: actors re-optimize rationally under changed constraints), and judicial discipline (Posner: courts provide the feedback loop that corrects regulatory error). See the MindCast AI framework:

Chicago School Accelerated, Part I: Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs

Chicago School Accelerated, Part II: Becker and the Economics of Incentive Exploitation

Chicago School Accelerated, Part III: Posner and the Economics of Efficient Liability Allocation

Classic Chicago assumes rational actors optimizing under stable rules. Behavioral economics explains what happens when salience bias causes firms to overweight credible hostility, when loss aversion triggers defensive repricing, when ambiguity aversion accelerates exit, and when present bias compounds layoffs because resolution timing is unknowable. Behavioral transmission speed-the rate at which regulatory signals move markets before litigation concludes-explains why iRobot was bankrupt before any court could evaluate the FTC’s theory.

The framework does not claim all merger challenges produce these effects. Rather, it identifies the conditions under which enforcement without adjudication becomes irreversibly harmful. Two recent cases-one in which courts intervened, one in which they did not-illustrate the mechanism.

IV. The Case Contrast: iRobot and Microsoft-Activision

The iRobot bankruptcy and the Microsoft-Activision litigation arose from the same enforcement regime, under the same leadership, applying similar speculative theories of future harm. Both transactions involved large platform companies acquiring content or product capabilities in markets already characterized by competition. Both faced FTC opposition grounded in forward-looking foreclosure narratives rather than demonstrated consumer harm. The outcomes diverged for one reason: courts intervened in Microsoft-Activision and were bypassed in iRobot.

A. iRobot: Enforcement Without Courts

Amazon’s proposed acquisition of iRobot tested whether the FTC could block a transaction without judicial review. iRobot was a declining mid-tier innovator facing intense global competition from subsidized Chinese manufacturers. The transaction offered capital access, logistics integration, and survival-scale coordination. Consumer prices were already falling, entry barriers were low, and the deal was not a horizontal merger. The case presented weak facts for a consumer-welfare-based challenge.

The FTC lacked a strong, litigable theory under U.S. antitrust law. Rather than force judicial review, the agency coordinated with European regulators operating under lower proof thresholds-a strategy exhibiting high adjudication avoidance and jurisdictional arbitrage. European resistance killed the deal without any U.S. court ruling on the merits.

Coordination architecture collapsed first. The FTC’s signal destroyed the focal point around which market participants had aligned: deal completion. Capital providers, suppliers, and partners lost their shared reference point. Trust density fell below the threshold required for cooperative interpretation.

Rational re-optimization followed. Loss aversion drove management to cut investment. Ambiguity aversion caused suppliers to reprice risk. Present bias accelerated layoffs. Behavioral responses compounded rational incentive shifts, producing bankruptcy faster than classic models predict.

Institutional correction never occurred. Because no court ruled on the merits, the FTC’s theory was never tested. The legal system never observed the causal loop, and doctrine cannot update based on unobserved consequences.

B. Microsoft-Activision: Enforcement With Courts

Microsoft sought to acquire Activision to expand content scale in a gaming market characterized by strong rivals and rapid innovation. The FTC challenged the deal in federal court, advancing a speculative theory of future foreclosure. Unlike iRobot, the case proceeded to full adjudication.

The court rejected the FTC’s narrative-based harm claims, finding no evidence tying the transaction to reduced output, higher prices, or diminished innovation. The deal closed. Investment continued. Coordination capacity expanded.

Courts reversed the behavioral cascade through four mechanisms: Ambiguity aversion reversed-judicial timelines replaced open-ended regulatory hostility. Present bias neutralized-deadlines and judgment dates created temporal anchors. Loss aversion bounded-court engagement required the agency to prove its theory. Focal point preserved-deal completion remained a viable coordination target.

C. The Causal Variable

The divergence cannot be explained by politics, leadership, or ideology-both cases arose under identical conditions. Court engagement isolated the mechanism: where adjudication constrained the agency, speculative theory was filtered, behavioral cascades reversed, and coordination capacity survived. Where courts were bypassed, harm became irreversible and unaccountable, and antitrust enforcement produced the opposite of its stated objective. To test whether this pattern reflects a structural shift rather than an isolated pair of cases, the analysis turns to an earlier enforcement regime that accepted courts as binding constraints.

V. Control Group: The Trump-Era Federal Trade Commission

The FTC’s enforcement posture shifted substantially between 2017 and 2021. Under the Trump administration, the agency operated within a consumer-welfare framework that treated courts as binding constraints on enforcement discretion. Commissioners prioritized cases with strong evidentiary foundations and accepted that losing in court was preferable to avoiding judicial review. The agency’s leadership viewed antitrust enforcement as requiring demonstrated harm to consumers-typically measured through price effects, output restrictions, or innovation suppression-rather than speculative theories of future market structure.

The Biden administration’s FTC, beginning in 2021 under Chair Lina Khan, adopted a different orientation. The agency embraced broader theories of harm rooted in market structure and competitive process rather than consumer welfare narrowly defined. Enforcement increasingly targeted transactions based on forward-looking concerns about market concentration, platform power, and potential foreclosure-theories that face higher evidentiary burdens in court. This doctrinal shift created tension: aggressive theories required judicial validation to become precedent, yet the same theories faced elevated risk of judicial rejection.

Two Trump-era cases illustrate the earlier posture. In FTC v. Qualcomm (2019-2020), the agency advanced an aggressive theory that Qualcomm’s licensing practices violated antitrust law. The FTC won at trial but lost decisively on appeal when the Ninth Circuit rejected the theory as economically unsound. The loss constrained future enforcement along that doctrinal path-but it also clarified legal boundaries. In FTC v. Steris (2015), the agency challenged a merger based on potential competition theories and lost in court. The defeat narrowed future action without causing irreversible market harm. In both cases, the agency submitted its theories to adjudication rather than relying on pre-litigation deterrence.

The control group demonstrates a structural point: losing in court can be a feature when it produces institutional learning. Court losses update doctrine by clarifying which theories survive judicial scrutiny. They constrain future overreach by establishing precedential boundaries. They prevent harm from compounding because markets can plan around known legal constraints. Court avoidance prevents all three. The Trump-era FTC is treated qualitatively because its function in this analysis is structural contrast-demonstrating that court engagement, even when it produces losses, generates institutional feedback that court avoidance forecloses. The question that follows is why an agency would choose avoidance over engagement when the costs of avoidance are so high.

VI. Institutional Substitution: Why Agencies Avoid Courts

The central finding of this analysis is not that agencies sometimes lose in court-that is expected and healthy. The central finding is that agencies facing weak legal theories have strong incentives to avoid courts entirely, and that court avoidance produces systematically worse outcomes than court losses. Understanding why requires examining how agencies substitute alternative tools when formal legal power is constrained.

A. Why Court Avoidance Is Rational for Agencies

Court avoidance is not an accident or a mistake-it is an equilibrium response to agency incentive structures. The payoff asymmetry is stark. Winning in court is hard, slow, public, and precedent-creating; the agency must prove its theory under evidentiary scrutiny, wait months or years for judgment, face appellate review, and accept that victory locks in doctrinal constraints on future discretion. Deterrence without court is fast, quiet, and framed as success: the deal is abandoned, the agency claims credit for protecting competition, and no precedent emerges to constrain future action. From the agency’s perspective, a blocked deal looks identical whether it results from a court injunction or from capital flight triggered by investigation overhang.

Internal agency incentives reinforce this asymmetry. Enforcement staff are evaluated on cases brought and outcomes achieved, not on theory validation or doctrinal development. A deal that collapses during investigation counts as a win; a deal that closes after the agency loses in court counts as a loss-even if the court loss clarifies legal boundaries and prevents future overreach. Budget justifications, congressional testimony, and public communications all reward transaction counts over judicial track records. The result is systematic pressure toward enforcement paths that maximize observable outputs while minimizing falsification risk.

Political and reputational salience compound the distortion. High-profile enforcement against large platform companies generates media coverage, congressional approval, and career advancement regardless of legal merit. The political reward for signaling hostility to big tech is immediate; the reputational cost of losing in court is diffuse and delayed. Commissioners seeking future appointments, staff seeking private-sector positions, and the agency seeking appropriations all benefit from aggressive posture whether or not theories survive judicial scrutiny. This is not cynicism-it is incentive alignment producing predictable behavior.

The framework therefore treats court avoidance as systematic, not accidental. The FTC’s handling of iRobot was not a one-off error correctable by better judgment or different leadership. It was the rational response of an institution whose incentive structure rewards deterrence over adjudication, process success over theory validation, and political salience over doctrinal coherence. Changing the outcome requires changing the incentives-which is why the predictions in Section IX focus on institutional behavior rather than personnel.

B. The Substitution Mechanism

Agencies possess enforcement tools beyond litigation: investigation costs, public signaling, and coordination with foreign regulators operating under lower proof thresholds. These tools exploit behavioral vulnerabilities-salience bias, loss aversion, ambiguity aversion-without triggering judicial review. The result is coercive narrative governance: influence achieved through behavioral leverage rather than adjudicated authority.

This substitution has a critical implication: court discipline on formal antitrust produces displacement, not restraint. When courts constrain the agency’s ability to win merger challenges on speculative theories, the agency does not abandon those theories-it migrates to enforcement tools that bypass courts. Investigation overhang replaces injunction. Reputational pressure replaces cease-and-desist. Cross-jurisdictional coordination replaces domestic adjudication. The agency’s revealed preference shifts from winning cases to deterring transactions, because deterrence requires only credible hostility while victory requires proof.

The consequences manifest in domains antitrust courts never observe: labor markets, capital flows, innovation metrics, competitive dynamics. When iRobot collapsed, no court ruled on the FTC’s theory, no precedent emerged, and no institutional learning occurred. The agency’s implicit theory-that blocking the acquisition would benefit consumers-was falsified by events, yet the falsification left no doctrinal trace.

Behavioral economists classify environments lacking timely, interpretable feedback as wicked learning environments: feedback is delayed beyond institutional memory, causation is obscured, and success metrics are manipulable. Court avoidance converts antitrust enforcement into a wicked learning environment. The agency cannot learn from iRobot because the consequences were never adjudicated-and may interpret deal abandonment as enforcement success rather than market harm.

Institutional substitution therefore predicts agency behavior following judicial losses. After Microsoft-Activision, the Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics framework predicts that the FTC will not improve its theories to survive future judicial scrutiny. Instead, the agency will adjust process strategy-pursuing enforcement paths where court avoidance is feasible, targeting transactions where parties lack resources to litigate, and coordinating with foreign regulators where domestic theories are weak.

The MindCast AI prediction is falsifiable: if the FTC responds to judicial losses by developing stronger evidentiary foundations and accepting court engagement, the framework is weakened. If the agency responds by intensifying pre-litigation deterrence and jurisdictional arbitrage, the framework is confirmed. The following section quantifies these dynamics through structured simulation.

VII. Diagnostic Summary

The preceding sections established the mechanism qualitatively: court avoidance enables behavioral cascades that produce irreversible harm. MindCast AI’s Cognitive Digital Twin simulation quantifies this mechanism by modeling regulators, firms, capital providers, and courts as boundedly rational actors responding to signals in real time. The methodology operationalizes Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics by tracking how regulatory posture propagates through coordination architecture before adjudication can constrain error.

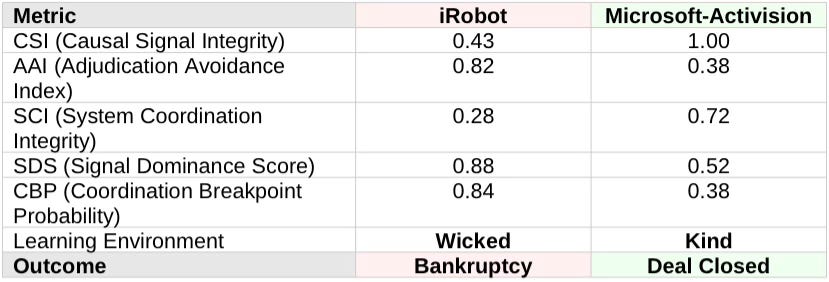

Five metrics distinguish correctable intervention from systemic failure.

Causal Signal Integrity (CSI) scores the evidentiary foundation of the agency’s harm theory-low CSI indicates the theory would likely fail under judicial scrutiny, making court avoidance strategically attractive.

Adjudication Avoidance Index (AAI) measures revealed preference for outcomes without merits adjudication, capturing tactics such as investigation delay, public signaling, and cross-jurisdictional coordination.

System Coordination Integrity(SCI) measures focal-point stability-the degree to which market participants share expectations about deal completion.

Signal Dominance Score (SDS) measures whether regulatory signals have displaced expected-value litigation reasoning in capital provider and counterparty decisions.

Coordination Breakpoint Probability (CBP) estimates the likelihood that coordination architecture collapses before any court can bound uncertainty. All metrics are reported on a normalized 0-1 scale for comparability across cases.

The metrics expose divergent enforcement paths. iRobot faced a high-avoidance posture (AAI = 0.82) in which the agency coordinated with European regulators rather than testing its theory in U.S. courts. Regulatory signaling dominated market reasoning (SDS = 0.88), coordination architecture collapsed (SCI = 0.28), and the probability of coordination breakpoint before adjudication was severe (CBP = 0.84).

The resulting learning environment was wicked: consequences manifested in domains antitrust courts never observed, and doctrine could not update. Microsoft-Activision faced lower avoidance (AAI = 0.38) because the agency was forced into court, where its speculative theory failed evidentiary scrutiny. Signal dominance was bounded (SDS = 0.52), coordination architecture survived (SCI = 0.72), and breakpoint probability remained manageable (CBP = 0.38). The learning environment was kind: courts provided interpretable, timely feedback that constrains future enforcement. Court engagement-not politics, not leadership, not ideology-constituted the difference.

Importantly, these metrics are not post hoc rationalizations constructed to explain known outcomes. Elevated AAI, collapsing SCI, and rising SDS appear early in the enforcement timeline-well before bankruptcy in the iRobot case, well before deal closure in Microsoft-Activision. The diagnostic signals would have predicted iRobot’s trajectory months before the company filed for bankruptcy, and would have predicted Microsoft-Activision’s resilience before the court ruled. This is what distinguishes the framework from narrative critique: the metrics generate ex ante predictions that can be tracked and falsified, not retrospective explanations fitted to results.

VIII. Practical Implications

The diagnostic framework is not merely descriptive. MindCast AI’s CDT simulation generates actionable guidance for practitioners who must navigate enforcement risk in real time.

For General Counsel and Deal Teams

Monitor behavioral signals, not just legal posture. Capital provider repricing and counterparty risk reassessment often begin before formal agency action. Early detection of focal-point erosion enables intervention before cascades become irreversible.

Force adjudication where possible. Court engagement bounds uncertainty and reverses behavioral cascades. A loss on the merits produces institutional learning; regulatory signaling without adjudication produces none.

Assess jurisdictional arbitrage risk from day one. When agencies cannot prevail in U.S. courts, they coordinate with foreign regulators operating under lower proof thresholds.

For Testifying Economists

Distinguish transaction costs from coordination costs. Regulatory intervention can destroy coordination architecture without raising legal fees or information asymmetries.

Model behavioral transmission speed explicitly. Expert testimony assuming rational actors wait for litigation outcomes will underpredict harm velocity.

Identify wicked learning environments. When agency tactics prevent adjudication, courts never observe harm, and doctrine cannot self-correct.

For Antitrust Economists in Consulting

Apply MindCast AI CDT diagnostics to deal risk assessment. CSI identifies whether the agency’s causal theory will survive evidentiary challenge. AAI and Jurisdictional Arbitrage Propensity (JAP) flag enforcement paths likely to avoid U.S. adjudication. SDS and CBP quantify whether regulatory signaling has already triggered capital provider repricing.

Track institutional learning failure. Low Institutional Update Velocity (IUV) predicts that judicial losses will not produce agency self-correction.

IX. Predictions

A framework that cannot be falsified is not analytically useful. Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics generates six predictions with explicit measurement thresholds. If these predictions fail, the framework weakens; if they hold, the framework demonstrates prospective diagnostic capacity that distinguishes it from retrospective critique.

1. Acquisition volume decline. Year-over-year acquisition volume in robotics, AI hardware, and biotechnology declines 15%+ within 24 months.

2. Foreign competitor gains. Market share in robotics or AI hardware shifts 10%+ toward non-U.S. manufacturers within 36 months.

3. Continued judicial rejection. The FTC loses three or more merger challenges on the merits within 24 months.

4. Indirect consumer harm. Consumer robotics product variety (distinct SKUs from U.S. manufacturers) declines 20%+ within 36 months.

5. Institutional re-anchoring. Congressional hearings on FTC court avoidance, proposed legislation requiring adjudication, or appellate procedural constraints occur within 24 months.

6. Process substitution. Within 24 months post-Microsoft-Activision, the FTC initiates three or more investigations relying on pre-litigation deterrence without pursuing merits adjudication.

Prediction tracking will be published through MindCast AI’s Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics series. Whether these predictions hold or fail will determine the framework’s prospective value.

X. Anticipated Objections

Three predictable objections merit direct response.

Objection: “Europe blocked the deal, not the FTC.” This objection misunderstands how global merger clearance works. Major transactions require approval from multiple jurisdictions, and sophisticated agencies exploit this architecture. When the FTC coordinated with European regulators-sharing theories, timing objections, and signaling joint hostility-it created a unified enforcement posture that Amazon and iRobot could not survive in any single jurisdiction. The FTC did not need to win in U.S. court; it needed only to ensure that some jurisdiction blocked the deal. Jurisdictional arbitrage is not a defense to the analysis-it is the mechanism the analysis identifies. The FTC’s revealed preference for European coordination over domestic adjudication is precisely what elevated AAI measures.

Objection: “iRobot was already failing-the FTC just accelerated the inevitable.” This objection confuses baseline decline with coordination collapse. iRobot faced competitive pressure, as do most acquisition targets-that is often why they seek acquirers. The relevant question is not whether iRobot would have thrived independently, but whether the FTC’s intervention destroyed coordination architecture that would otherwise have enabled the transaction to close. The evidence is unambiguous: Amazon offered $1.7 billion for a company that, eighteen months later, filed for bankruptcy. The delta between those states is not explained by competitive pressure alone. It is explained by capital flight, supplier repricing, and management retrenchment-all triggered by regulatory signaling that the FTC never had to defend in court.

Objection: “Speculative harm must be addressed early, before it materializes.” This objection has surface appeal but inverts the burden of proof. Antitrust enforcement is supposed to prevent consumer harm, not cause it. When the agency’s theory is speculative-as it was in both iRobot and Microsoft-Activision-the appropriate response is to test the theory in court, where evidentiary discipline can distinguish valid concern from narrative overreach. The iRobot case demonstrates what happens when speculative theories bypass adjudication: the agency’s implicit prediction (that blocking the deal would benefit consumers) was falsified by events, yet no institutional learning occurred. Worse, the agency may have interpreted deal abandonment as validation. This is the defining characteristic of a wicked learning environment: the feedback loop that would constrain error is severed. Early intervention is justified only when it is disciplined intervention-subject to the evidentiary scrutiny that courts provide and that pre-litigation deterrence evades.

XI. Conclusion

The iRobot bankruptcy exposes the cost of enforcement that evades judicial discipline. When the FTC signaled opposition to the Amazon acquisition, that signal propagated through capital markets faster than any court could evaluate the underlying theory.

Capital providers repriced risk and withdrew.

Suppliers and partners began treating deal failure as the base case.

Coordination architecture fractured along the fault lines that behavioral economics predicts: salience bias amplified the credibility of regulatory hostility, loss aversion triggered defensive retrenchment, ambiguity aversion accelerated exit, and present bias compressed the timeline because resolution timing was unknowable.

By the time the deal collapsed, iRobot lacked the capital to survive independently. The harm that followed-job losses, narrowed consumer choice, foreign competitors gaining market position-directly contradicted the consumer-welfare rationale the agency invoked, yet no court ever ruled on the merits, no institutional correction occurred, and antitrust doctrine learned nothing.

Microsoft-Activision demonstrates that court engagement reverses each element of this cascade. Judicial timelines bounded uncertainty. Procedural discipline narrowed downside risk. Capital providers maintained position because the agency had to prove its theory rather than simply assert it. The focal point of deal completion survived regulatory challenge, coordination architecture remained intact, and the transaction closed. The FTC lost on the merits, yet that loss-unlike the iRobot outcome-produced institutional feedback that constrains future enforcement and prevents harm from compounding.

Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics does not argue for weaker antitrust enforcement. It argues for disciplined enforcement-intervention that submits its theories to adjudication before behavioral responses lock in irreversible harm. The causal sequence this analysis identifies is clear: when agencies degrade coordination architecture through regulatory signaling, rational actors re-optimize toward exit, and harm compounds in domains-labor markets, capital flows, innovation capacity-that antitrust courts do not observe and antitrust doctrine does not track. Breaking any link in this chain-by preserving coordination architecture, by altering incentive gradients, or by restoring judicial discipline-prevents the cascade. Until enforcement submits to that discipline, iRobot will not be the last casualty.