MCAI National Innovation Vision: Aerospace’s Warning to AI, How Capability Laundering Will Reshape Corporate Compliance

What Nvidia’s Indonesia Leak Reveals About the Next Era of U.S. Controls, Corporate Risk, and Global Compute Distribution

See also MCAI National Innovation Vision: Foresight Simulation of NVIDIA H200 China Policy Exploits Vectors (Dec 2025).

I. Executive Summary

The AI industry has arrived at the same crossroads aerospace faced thirty years ago, where advanced technology becomes a geopolitical asset and its distribution becomes a national‑security concern. The recent appearance of Nvidia’s top-tier chips in an Indonesian data center—paired with compute access granted to a Chinese AI firm—demonstrates that the point of vulnerability is no longer the movement of hardware but the movement of capability. For compliance leaders, this means the traditional focus on physical export controls is no longer sufficient.

Aerospace offers the clearest historical analogue. For decades, U.S. avionics, composite materials, guidance systems, and propulsion technologies leaked through friendly intermediaries, foreign repair hubs, and service-based access arrangements. The same incentive structures—profit, plausible deniability, and jurisdictional distance—now shape AI compute access. The lesson is direct: corporate compliance must shift its lens from hardware governance to access governance.

The following pages integrate full Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) simulations for the U.S. Government and U.S. Firms, offering a foresight-grounded roadmap for compliance teams designing controls, policies, and monitoring architectures between 2025 and 2030.

II. The Nvidia–Indonesia–China Route: A Modern Capability Detour

The Nvidia–Indonesia incident becomes clearer when concrete details are added. Between late 2024 and mid‑2025, approximately 2,300 Nvidia H100 and early‑run Blackwell (B200‑class) GPUs were routed to an Indonesian data‑center cluster operated by Indosat Ooredoo Hutchison. These units were originally assembled into 32 high‑density server racks by Aivres Systems—a U.S. distributor in which Inspur, a blacklisted Chinese firm, holds a one‑third ownership stake. The hardware was delivered legally under U.S. rules because Indonesia is not a restricted jurisdiction and the initial transaction occurred through a compliant U.S. intermediary.

The Chinese end‑user, INF Tech, is a Shanghai‑based AI developer specializing in enterprise‑scale large‑language‑model training. Public reporting indicates the firm used the Indonesian compute to run fine‑tuning workloads and multimodal inference pipelines, specifically workloads that would have exceeded U.S. export‑control thresholds had they been run on hardware located inside China. Access was detected after a combination of commercial disclosures, Indosat’s own investor communications, and U.S. supply‑chain intelligence highlighted that Chinese engineers were remotely authenticating into Indonesian GPU clusters.

A rough timeline shows the pattern: hardware sale in Q3 2024, shipment and installation in Jakarta by early Q4, onboarding of Chinese clients by year‑end, and public exposure by early 2025. The chain of events shows how compute migrates through legal channels until the moment of access—where intent changes but the enforcement framework lags. The implications for compliance are immediate: the operational chokepoint has shifted from physical custody to remote utilization.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on foresight simulations in industrial policy. See also MindCast AI publications Foresight Analysis in Illegal GPU Export Pathways (2025–2030) (Nov 14 2025), commenting on US DOJ Release: U.S. Citizens and Chinese Nationals Arrested for Exporting AI Technology to China; and The Global Innovation Trap, Why Your R&D Investment Is Funding Competitors (Nov 22, 2025).

III. Aerospace as a Mirror: How Leakage Became Systemic

Aerospace teaches that leakage does not happen by accident—it happens by design. For decades, U.S. components were legally exported to friendly nations, only to be diverted through opaque supply chains or repurposed through service partnerships that gave sanctioned actors access without ownership. These channels thrived because intermediaries faced little enforcement pressure, and corporate compliance frameworks assumed physical custody equaled control.

The predictive structure is appearing again in AI. A clear aerospace example illustrates the pattern: in the late 1990s, U.S.‑made satellite components were legally sold to European manufacturers under permissive export rules. These components were later integrated—through joint ventures and technology‑sharing agreements—into Chinese communications satellites, some of which supported military applications. The initial sale was lawful, the intermediaries were friendly jurisdictions, and yet the capability migrated into restricted hands through a chain of opaque partnerships.

The structural resemblance to the Nvidia–Indonesia route is unmistakable: legal origin, intermediary conductivity, and ultimate capability transfer despite formal compliance barriers. Countries with strong commercial ambitions but weaker export-control enforcement—Indonesia, UAE, Malaysia, Turkey, and Vietnam—are becoming compute transshipment hubs in the same way they once became aerospace parts conduits. Compliance programs must assume that capability will seek its easiest path through these jurisdictions.

The core lesson is that leakage is not an anomaly but a recurring pattern. Compliance systems must be designed to anticipate it rather than react to it.

IV. Lesson One: The Access Layer Is the Real Export

Aerospace learned that even if hardware is controlled, access can still be rented, shared, or outsourced. Foreign MRO centers, simulation labs, and testing facilities provided adversaries with the functional benefits of U.S. technology without transferring the underlying components. AI compute behaves the same way: remote access to GPUs gives an adversary the same developmental capability as physical possession of chips.

For compliance teams, this means access governance must become central. Cloud workloads require identity verification, usage logging, geo-fenced orchestration, and red-flag detection. Without these measures, organizations will be blind to how their own infrastructure may be indirectly supporting restricted actors.

Ultimately, hardware rules alone cannot secure strategic technologies. Compliance must treat compute access as the new export boundary.

V. Lesson Two: Third Countries Are the New Capability Laundromats

Aerospace demonstrated that third-country jurisdictions with flexible enforcement postures act as ideal intermediaries for capability laundering. They offer plausible deniability, regulatory neutrality, and commercial opportunity. The same incentive structures now shape AI compute distribution across Southeast Asia and the Gulf.

For compliance departments, this means that jurisdictional risk scoring must include an assessment of political neutrality, enforcement discipline, and susceptibility to external influence. Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, UAE, Thailand, and Turkey are not inherently high-risk, but they are structurally conductive. They allow adversaries to acquire capability without triggering direct scrutiny.

Compliance teams must recognize that the “middle” of the supply chain is where the risk increasingly concentrates. Controls must follow capability, not geography.

VI. Lesson Three: Minority Chinese Ownership Creates Compliance Blind Spots

Aerospace repeatedly revealed that minority ownership stakes by Chinese entities inside foreign intermediaries can reshape operational decisions, visibility, and customer targeting. These ownership structures do not need to be controlling to be strategically meaningful—they only need to provide influence, data access, or insight into market flows.

In the Nvidia–Indonesia incident, a partner with one-third Chinese ownership served as a conduit. The issue was not the legality of the sale but the alignment of incentives and the opacity of beneficial ownership. Compliance teams must now incorporate ownership-forensics into their onboarding, monitoring, and renewal processes.

A particularly acute blind spot emerges when distributors, cloud partners, or integrators operate through joint ventures with opaque or partially disclosed ownership. Aerospace provides multiple precedents: JVs that appeared compliant on paper but ultimately funneled U.S. technology into Chinese or Russian programs via undisclosed intermediate partners. When ownership stakes are layered through holding companies, offshore vehicles, or silent partners, influence can be exerted without appearing anywhere in official documentation.

Compliance programs must treat any JV with unclear beneficial ownership, offshore incorporation, or rapid equity turnover as a high-risk entity requiring enhanced due diligence. Key red flags include:

absence of a transparent cap table,

unexplained capital injections from non-allied jurisdictions,

JV partners that refuse to disclose indirect owners,

or multi-tiered holding structures masking ultimate beneficiaries.

JVs with opaque ownership may represent the most dangerous leakage vector of all and should trigger enhanced review cycles.

The result is clear: ownership structure is now a risk category, not a footnote.

VII. Government CDT Profile: Regulatory Playbook and Enforcement Roadmap

Before examining the emerging policies, the analysis clarifies the CDT used here: a behavioral model synthesizing BIS, DoD, State, and NSC incentive structures. This CDT focuses on specific regulatory levers rather than export‑control philosophy—highlighting the specific regulatory levers most likely to be deployed as capability‑laundering risks escalate.

The Nvidia–Indonesia case exposed the precise failure mode the government anticipated but had not yet structured controls around: remote training on unrestricted foreign soil using U.S. GPUs. As a result, agencies are now converging on a set of tools that shift oversight from hardware to usage.

Regulatory Mechanisms Likely to Advance (2025–2027)

Quarterly Workload‑Audit Mandates (Q3 2026): Tier‑1 clouds (AWS, Microsoft, Google, Oracle) must submit workload identities, compute classes, and geographies.

Compute‑Access Licensing (Pilot 2026 → Full 2027): Sensitive jurisdictions (Indonesia, UAE, Malaysia, Vietnam) require licenses for high‑intensity training workloads.

Mandatory Beneficial‑Ownership Attestations (Q1 2026): Distributors with >10% non‑allied ownership require enhanced due diligence or recertification.

Cross‑Border Training Restrictions (Late 2026): Remote training above compute thresholds treated as a regulated activity, regardless of server location.

Jurisdiction‑Bound Compute Enclaves (2027): Clouds must implement region‑locked training environments for export‑controlled workloads.

This roadmap provides the compliance architecture that firms should anticipate. Agencies will test reporting first, licensing second, and workload‑bounded enforcement third. Organizations that align early reduce risk, avoid surprise retrofits, and maintain frictionless government relationships.

VIII. US Firms CDT Profile: Compliance‑Centric Commercial Strategy

The US Firms CDT models how semiconductor companies, cloud providers, and distributors adapt when regulatory gravity shifts toward access‑layer oversight. Unlike Sections IV–VI, this section does not revisit principles. It details the tactical responses U.S. firms will deploy as they redesign compliance for competitive advantage.

Corporate Adaptation Mechanisms (2025–2027)

Six‑Month Distributor Due‑Diligence Cycles (2025): Automatic recertification for intermediaries with >10% non‑allied ownership.

Three‑Tier Compute Segmentation (2025–2026): Safe (U.S./EU/Japan), Caution (ASEAN/UAE/India), High‑Risk (China/Russia) tiers with distinct onboarding, controls, and logging.

Location‑Locked Training Environments (2026): Workloads cannot migrate across regions without compliance authorization.

Identity‑Anchored Compute Access (2025–2027): High‑end compute tied to verified corporate identity, leadership attestation, and beneficial‑ownership transparency.

Real‑Time Workload Classification (2026): Automated classifiers identify attempts to fine‑tune restricted model types or exceed export thresholds.

Shift to Controlled Compute Offerings (2027): U.S. chipmakers pivot from hardware sales in conductive jurisdictions to cloud‑mediated compute with full observability.

The US Firms CDT emphasizes execution: companies that operationalize these mechanisms earliest will define compliance norms and secure regulator trust. Those that lag will face market access constraints in regions that become regulated zones.

IX. Integrated Outlook: Compliance Trajectory Forecast (2025–2030)

Sections VII and VIII identify the control levers and corporate responses. This section integrates both CDTs into a forward‑looking forecast—giving compliance leaders a unified timeline to plan staffing, tooling, and policy cycles.

Timeline of Likely Developments

2025: BIS cloud‑access guidance; first distributor‑ownership audits.

2026: Pilot compute‑access licensing; early geo‑fenced training zones.

2027: Activity‑based controls integrated into EAR; mandatory workload‑identity logging.

2028: Industry‑standard Trusted Distributor Networks; regulated third‑country compute hubs.

2029–2030: Global alignment of compute‑access regulations across U.S., EU, Japan.

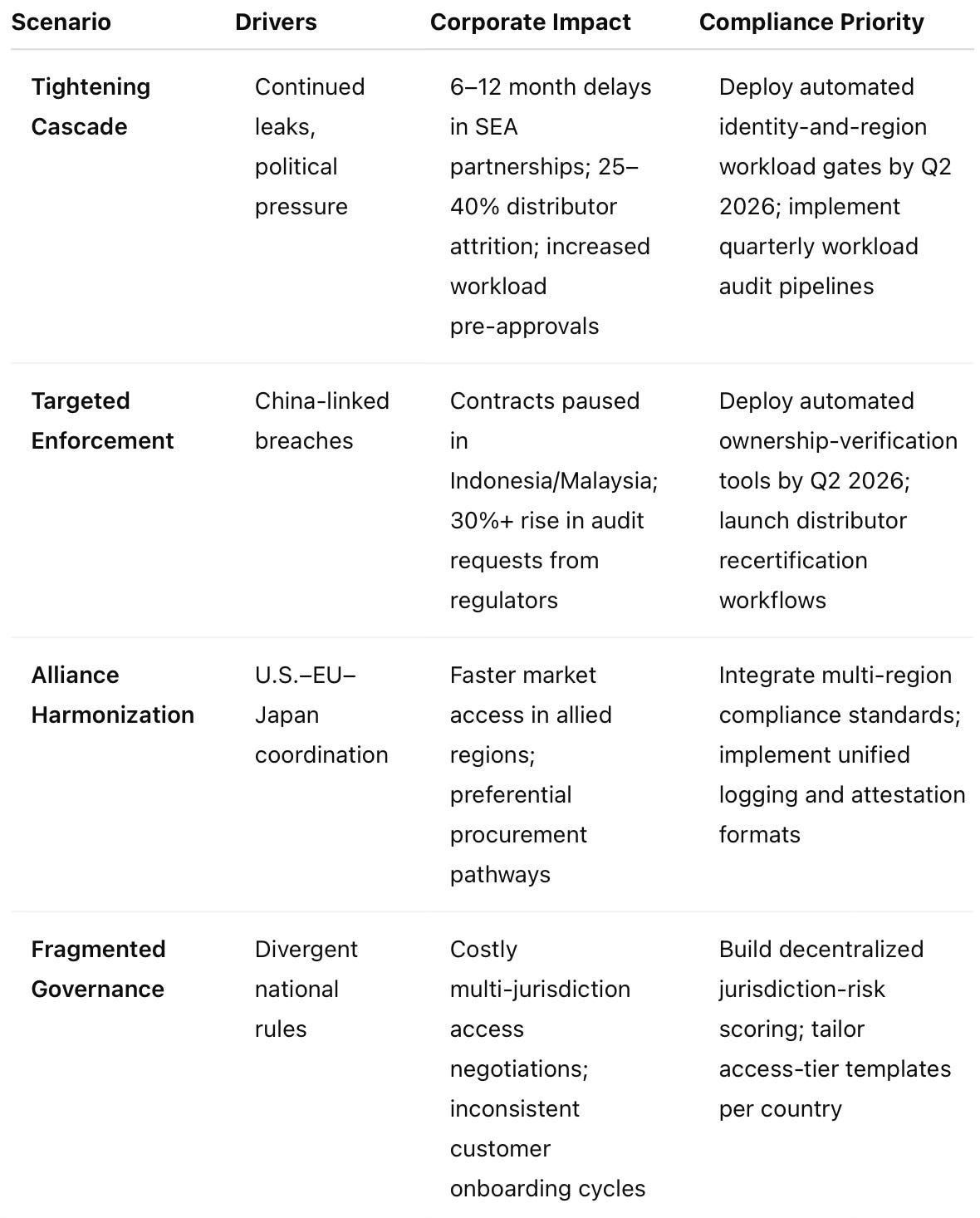

Scenario Matrix for Compliance Planning

This integrated forecast allows compliance teams to translate CDT outputs into concrete planning assumptions and operational timelines.

Red Flags Requiring Immediate Compliance Review

Compliance leaders can quickly assess their organization’s exposure by monitoring for the following high‑signal indicators. The presence of even one suggests the firm requires urgent modernization of access‑layer controls:

Any distributor or integrator with >5% Chinese or other non‑allied ownership involved in GPU sales, cloud provisioning, or system integration.

Unexplained or unmonitored workload traffic from restricted or high‑risk jurisdictions (e.g., China, Russia, Iran) into company infrastructure.

Inability to trace compute consumption by end‑user identity across cloud, hybrid, or on‑prem environments.

Training workloads crossing regional boundaries without explicit authorization, especially between low‑risk and high‑risk jurisdictions.

Customer onboarding workflows that lack beneficial‑ownership verification or do not require leadership attestation.

Absence of automated classification tools to detect high‑intensity or export‑restricted model‑training jobs.

No geo‑fencing controls restricting where sensitive AI workloads may execute.

Legacy distributor agreements without periodic recertification, ownership refresh, or influence‑mapping.

Firms encountering any of these signals should escalate to immediate compliance review and begin modernization efforts within the next cycle.

X. Strategic Implications: The 2026 Inflection Point and Competitive Positioning

The sector is approaching a structural breakpoint: 2026 is the year when access‑layer compliance becomes inseparable from commercial viability. By that point, BIS workload audits, distributor‑ownership rules, and early compute‑access licensing will begin to harden. Firms that have not modernized their compliance infrastructure by then will struggle to meet new requirements without significant operational disruption.

Why 2026 Matters Most

2026 is the convergence point where regulatory tightening, geopolitical pressure, and cloud‑infrastructure redesign intersect. It is the first year when:

cloud providers must produce auditable workload‑identity logs,

distributors face formal beneficial‑ownership attestation cycles,

compute‑access licensing expands beyond pilot scale,

and regional workload restrictions become enforceable. This creates a measurable compliance burden—and an opportunity for firms that prepared early.

Three Actions for Board‑Level Positioning (2025–2026)

Commit to Access‑Layer Investment: Boards should authorize a 15–25% increase in compliance‑technology spend focused on workload tracing, identity systems, and geo‑fencing controls.

Redesign Third‑Country Exposure: Create clear corporate policies defining which jurisdictions can host sensitive workloads and under what controls.

Establish Beneficial‑Ownership Forensics as a Standard: Require full transparency for any partner with >5–10% non‑allied ownership. These actions position firms ahead of rulemaking rather than behind it.

The Compliance Budget Question

Compliance is no longer a back‑office maintenance cost—it is a forward investment that determines whether a firm can access regulated markets. Between 2025 and 2027, firms should expect:

15–25% growth in compliance‑tech spend,

expansion of compliance teams by 20–35%, and

migration to automated classification and identity‑anchored systems. Many firms that delay modernization will incur significant retrofit expenses. Based on aerospace precedents and cloud‑infrastructure rewiring cycles, late adopters face estimated $10–50 million in remediation costs to rebuild logging pipelines, identity controls, and distributor‑verification systems under compressed timelines. These investments reduce long‑term adaptation costs and create durable operational advantages.

The Competitive Moat: Trusted Infrastructure Status

The coming decade will reward firms that treat compliance as a product differentiator. Early investment in traceability, identity assurance, and jurisdictional control will:

secure preferred‑vendor status with regulated entities,

strengthen trust with the U.S. government and allied regulators,

and create defensible moats that competitors cannot easily replicate. As compute access becomes a strategic currency, the ability to demonstrate regulatory trustworthiness becomes a core business asset.

Policy Recommendations (For Policymakers and Regulators)

To reinforce the stability of the global compute ecosystem and prevent capability laundering, policymakers should consider:

Formalizing Compute‑Access Licensing: Treat cross‑border training above threshold compute levels as a licensable activity.

Requiring Standardized Workload Identity Logs: Implement common formatting, fields, and retention rules across all Tier‑1 cloud providers.

Mandating Beneficial‑Ownership Transparency: Require disclosure of all direct and indirect owners with >5% non‑allied stakes for distributors, integrators, and cloud partners.

Establishing Third‑Country Risk Tiers: Publish jurisdictional compute‑risk categories to guide firms’ onboarding and workload‑routing decisions.

Launching Joint Enforcement with Allies: Create U.S.–EU–Japan enforcement corridors that harmonize cloud audit rules and prevent regulatory arbitrage. These measures strengthen export controls without stifling innovation and give compliance teams a stable architecture to build against.

XI. Closing Perspective

The firms that emerge as trusted infrastructure providers by 2028 will be those that treated compliance as a competitive system starting in 2025. In an era when capability laundering threatens national security and corporate liability, the winners will be the organizations that internalize compliance as a forward‑looking, predictive discipline—one that shapes strategy rather than reacts to it.