MCAI Lex Vision: Compass's Coasean Coordination Problem Part V- Coordination Costs, Platform Antitrust, and the Modern Chicago School of Law and Behavioral Economics

Why the NWMLS and Zillow Cases Must Be Evaluated Together

MindCast AI Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem series is part of our Chicago School Accelerated Part I: Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs (December 2025) framework, with sub-series:

Part I How Private Exclusives Reshape Competition and Threaten MLS Stability

Part III Coordination Costs, MLS Governance and the Compass Litigation

Part IV Platform Routing, Portal Power, and the Zillow Litigation

Executive Overview

Series Chronology

The MindCast AI series Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem develops a unified analytical framework across five installments. Each part addresses a distinct dimension of coordination-cost economics; together, they demonstrate that the Compass litigation complex represents a single coordination-degrading strategy requiring joint evaluation.

Chicago School Accelerated Part I: Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs

Foundation: Establishes the core theoretical distinction between transaction costs (friction within bargaining) and coordination costs (whether bargaining can engage at all). Introduces the three components of coordination capacity: focal-point availability, narrative alignment, and trust density. Leverages MindCast AI’s proprietary Cognitive Digital Twins (CDTs) to modernize the Chicago School of Law and Economics with behavioral economics AI foresight simulations.

Chicago School Accelerated Contribution to Part V: Provides the economic vocabulary that transforms intuitions about ‘procompetitive conduct’ into measurable coordination variables. Establishes that zero transaction costs do not guarantee efficient outcomes when coordination architecture is absent—the analytical foundation for recognizing MLS governance as coordination infrastructure rather than cartel restraint.

Part I How Private Exclusives Reshape Competition and Threaten MLS Stability

Diagnosis: Applies coordination-cost economics to Compass’s Private Exclusive strategy. Demonstrates that Private Exclusives attack all three coordination mechanisms simultaneously—fragmenting the focal point, contesting the reciprocity narrative, and degrading trust through selective disclosure. Projects three macro-scenarios through 2030: coordination collapse (48%), MLS stability (32%), and hybrid architecture (20%).

Contribution to Part V: Establishes the baseline coordination collapse probability and identifies the 2025–2027 intervention window. Introduces the CDT metrics (CSI, CTS, FIS) that Part V uses to quantify institutional behavior across the litigation complex. Demonstrates that regulators applying transaction-cost logic to coordination problems will systematically mis-specify harm.

Part II The Litigation–Acquisition Monopolization Strategy

Scale Analysis: Models how the Compass–Anywhere merger would accelerate coordination collapse by routing opacity through national scale. Introduces the three-prong monopolization strategy: NWMLS lawsuit (remove internal constraints), Zillow lawsuit (build external routing infrastructure), Anywhere acquisition (acquire national distribution). Demonstrates that coordination degradation marginal at local scale compounds to systemic risk at national scale.

Contribution to Part V: Reveals the strategic coherence linking apparently contradictory litigation positions. Establishes that the NWMLS and Zillow lawsuits are complementary components of a unified strategy—the analytical foundation for Part V’s joint-evaluation thesis. Provides the scenario lattice showing how merger clearance pathways interact with litigation outcomes.

Part III Coordination Costs, MLS Governance and the Compass Litigation

Litigation Analysis (Internal Layer): Examines the NWMLS case as prong one of the monopolization strategy. Identifies eight gaps in NWMLS’s Reply brief where correct conclusions lack compelling explanations. Provides coordination-cost vocabulary to transform the defense from ‘we did not do anything wrong’ to ‘Compass is attacking coordination infrastructure.’ Addresses expert testimony strategy and Daubert compliance for CDT methodology.

Contribution to Part V: Establishes that mandatory submission rules are joint-venture governance preserving market completeness—not horizontal restraints suppressing competition. Introduces the 2.9% price admission as legally dispositive under two-sided market analysis. Provides the internal-layer analysis that Part V synthesizes with external-layer (Zillow) analysis.

Part IV Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part IV- Platform Routing, Portal Power, and the Zillow Litigation

Litigation Analysis (External Layer): Examines the Zillow case as prong two of the monopolization strategy. Introduces the aggregation-routing distinction: aggregation reduces search costs; routing determines whether coordination occurs. Demonstrates that the requested injunction—compelled transmission of non-MLS inventory—is itself the coordination harm. Develops the cross-case outcome matrix showing interdependencies between NWMLS and Zillow outcomes.

Contribution to Part V: Establishes that Zillow’s Listing Access Standards are coordination-preserving curation, not exclusionary conduct. Demonstrates that the same 2.9% admission creates cross-case vulnerability—Compass cannot argue opposite positions in different forums. Provides the external-layer analysis and cross-case matrix that Part V uses to argue for joint evaluation.

Part V: The Synthesis (what you’re reading now)

Part V synthesizes the preceding analyses into a unified framework for joint evaluation. Where Parts III and IV analyzed the NWMLS and Zillow cases separately, Part V demonstrates why they must be evaluated together. Where Parts I and II established coordination-cost economics conceptually, Part V applies that framework to generate specific doctrinal holdings and agency guidance. The synthesis shows that isolated evaluation is not analytically neutral—it systematically advantages coordination attackers while disadvantaging coordination defenders. Joint evaluation corrects this procedural asymmetry while aligning with Chicago School insistence on parsimony and effects-based reasoning.

Part V advances a single, integrated claim: the Compass–NWMLS and Compass–Zillow litigations represent one coordination-degrading strategy implemented across two institutional layers, and antitrust analysis must evaluate them jointly to avoid analytical error and remedial incoherence.

Traditional Chicago School antitrust correctly rejected formalism in favor of effects-based analysis. But platform markets expose a blind spot in orthodox application: coordination costs—not transaction costs—often dominate welfare outcomes in multi-sided markets that depend on comprehensive information aggregation and shared focal points. Residential real estate is a canonical example.

MindCast AI’s Modern Chicago School framework does not reject Chicago economics; it completes it. The framework extends consumer-welfare analysis to institutional design, information routing, and network completeness—variables already implicit in Supreme Court precedent on joint ventures, information control, essential facilities, and two-sided markets.

Viewed in isolation, the NWMLS case appears to challenge internal governance rules; the Zillow case appears to challenge external platform standards. Viewed together, they target the same economic asset: control over listing visibility as a substitute for market-wide coordination. Granting relief in either case raises coordination costs. Granting relief in both institutionalizes opacity.

Courts and regulators do not need new statutes to address this conduct. Existing doctrine already permits it. What is required is explicit recognition of coordination capacity as a competitive variable, and joint evaluation of remedies that affect the same coordination infrastructure through different legal wrappers.

Part V provides regulators and courts with:

A doctrine-consistent framework for joint evaluation

An economic foundation grounded in Chicago School welfare analysis

A narrow path for precedent that applies beyond real estate to platform markets generally

CDT metrics that operationalize coordination capacity as a measurable antitrust variable

Roadmap

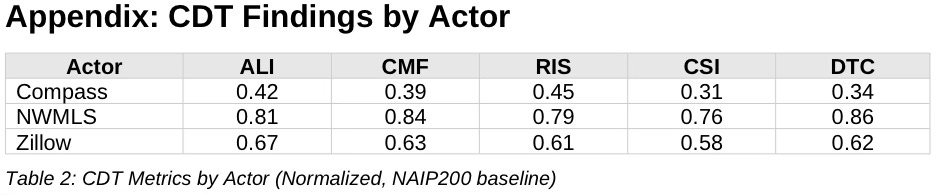

Section I diagnoses the analytical error of evaluating the NWMLS and Zillow cases in isolation. Case fragmentation is not procedurally neutral—it advantages coordination attackers by preventing courts from seeing the unified strategy. The sham litigation doctrine from California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited (1972) provides the framework for evaluating multi-forum petitioning patterns. CDT metrics quantify strategic fragmentation: Compass’s Causal Signal Integrity (CSI 0.31—measuring alignment between stated rationales and observed conduct) reveals systematic divergence across both forums.

Section II establishes the Chicago School foundations properly applied. The consumer welfare standard extends beyond price to information completeness and search costs. Transaction costs (friction within bargaining) are analytically independent from coordination costs (whether bargaining can engage at all). George Akerlof’s ‘Market for Lemons’ (1970) provides the canonical economic demonstration: when database completeness becomes uncertain, the market spirals toward adverse selection—the precise dynamic Private Exclusives introduce.

Section III demonstrates that existing legal doctrine already fits coordination-cost analysis. Rothery Storage v. Atlas Van Lines (D.C. Cir. 1986, Judge Bork) directly validates mandatory submission rules: networks may prohibit agents from ‘vest pocketing’ inventory that free-rides on shared infrastructure. Joint venture precedent (BMI, NCAA, Northwest Wholesale Stationers) permits contribution requirements. Information control doctrine (Container Corp., RealPage enforcement) treats routing as a competitive variable. Essential facilities analysis (Trinko) distinguishes compelled misuse from compelled denial.

Section IV presents the unified coordination harm across internal (MLS) and external (portal) layers. MLS submission rules preserve information completeness (DTC 0.86). Continental T.V. v. GTE Sylvania (1977) validates Zillow’s routing standards as vertical restraints promoting interbrand competition: portals may condition display on coordination compliance to differentiate their product. The Remedy Sensitivity Gradient shows harm compounds nonlinearly when both layers weaken simultaneously.

Section V identifies Compass’s dispositive economic admission. The claimed 2.9% price effect from Private Exclusives is legally fatal under Ohio v. American Express: in two-sided markets, seller price uplift necessarily implies buyer harm. Compass cannot claim the same conduct is procompetitive in one forum and anticompetitive in another.

Section VI argues for joint evaluation as a doctrine-reducing move. Chicago parsimony favors one theory and one effects analysis over duplicative proceedings reaching inconsistent conclusions. Remedies designed in isolation may neutralize each other or compound harm.

Section VII specifies the precedent courts and agencies can set. The minimalist judicial holding: coordination-preserving governance is presumptively procompetitive absent demonstrated welfare harm. The administrable agency framework: a five-factor test operationalizing coordination capacity through CDT metrics.

Section VIII extends the framework beyond real estate to digital marketplaces, ad tech, and labor platforms. The coordination-cost lens applies wherever platform architecture determines whether coordination occurs—a growing share of economic activity.

Section IX concludes with the four propositions defining the Modern Chicago School: coordination capture is condemned regardless of legal wrapper; platform architecture is conduct subject to antitrust scrutiny; joint evaluation is analytically superior to isolation; and existing doctrine is sufficient for these holdings.

I. The Analytical Error of Isolation

Thesis: Treating the Compass–NWMLS and Compass–Zillow cases as separate disputes mis-specifies the competitive harm and invites inconsistent remedies.

Federal antitrust litigation proceeds case-by-case. Courts evaluate claims as presented, within their assigned jurisdictions, against the parties before them. This procedural structure creates an analytical vulnerability when a single actor pursues a unified strategy through multiple legal vehicles. The cases appear independent. The coordination harm is invisible.

The Compass litigation complex presents precisely this structure. In the Western District of Washington, Compass challenges NWMLS mandatory submission rules as horizontal restraints that suppress ‘seller choice.’ In the Southern District of New York, Compass challenges Zillow’s Listing Access Standards as monopolistic exclusion that prevents ‘fair distribution.’ The claims invoke different legal theories, name different defendants, and appear in different circuits.

Yet the claims target the same economic asset: market-wide coordination capacity. MLS mandatory submission preserves coordination from within by requiring inventory contribution as a condition of data access. Zillow’s routing standards preserve coordination from without by conditioning aggregation on prior MLS routing. Together, these mechanisms maintain the focal-point architecture that enables forty-five trillion dollars in residential real estate to match efficiently.

Compass attacks both mechanisms simultaneously. The NWMLS lawsuit seeks to invalidate internal constraints on inventory withholding. The Zillow lawsuit seeks to force external distribution of inventory that bypassed internal constraints. Success in either case fragments coordination architecture. Success in both institutionalizes opacity as the market default.

I.A. Fragmentation as a Litigation Strategy

Thesis: Compass’s claims are structured to force courts to evaluate internal rules and external platforms independently, obscuring their cumulative effect on coordination.

The procedural separation is not accidental. Compass filed against NWMLS in Seattle and against Zillow in New York—ensuring that neither court would have full visibility into the unified strategy. Each court sees only its assigned dispute. Neither court is positioned to evaluate how relief in one case interacts with relief in the other.

MindCast AI’s Cognitive Digital Twin methodology quantifies this strategic fragmentation. Compass’s Causal Signal Integrity (CSI) score of 0.31 reflects an institution whose stated positions systematically diverge from observed conduct. The company claims to advance consumer welfare while pursuing strategies that measurably degrade market coordination. The litigation fragmentation obscures this divergence by preventing any single tribunal from seeing the complete picture.

Compare NWMLS (CSI: 0.76) and Zillow (CSI: 0.58). Both institutions exhibit substantial alignment between stated positions and observed behavior. NWMLS articulates coordination preservation as its mission and enforces rules consistent with that mission. Zillow articulates ‘broad exposure’ as its standard and implements routing requirements consistent with that standard. Compass articulates ‘consumer choice’ while systematically reducing consumer access to market information.

The litigation structure is itself evidence of strategic intent. An actor genuinely seeking market access would consolidate claims to obtain comprehensive relief. An actor seeking to disable coordination architecture benefits from fragmentation—forcing defenders to litigate on multiple fronts while preventing courts from seeing the cumulative harm.

This pattern raises questions under the ‘sham litigation’ exception to Noerr-Pennington immunity recognized in California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508 (1972). The Supreme Court held that litigation loses First Amendment protection when it constitutes ‘a pattern of baseless, repetitive claims’ designed to abuse judicial process rather than legitimately redress grievances. The doctrine does not require that each individual claim lack merit—it asks whether the pattern of petitioning, viewed as a whole, is designed to impose costs on rivals rather than obtain judicial resolution.

Whether Compass’s litigation pattern satisfies this standard is a question for the courts. What the pattern doesdemonstrate—independent of any sham-litigation finding—is the analytical error of isolated evaluation. The company simultaneously challenges: (1) NWMLS mandatory submission rules that have operated for decades without prior antitrust challenge; (2) Zillow routing standards that apply neutrally to all brokerages; (3) NAR cooperative compensation rules through both litigation and lobbying. Each action targets a different institution. Each invokes different legal theories. But all target the same economic function: coordination-preserving governance.

This analysis does not prejudge the merits of any individual claim. It identifies a pattern whose cumulative effect—regardless of individual outcomes—is to impose coordination costs on the market. Even if Compass prevails in every case, the litigation itself degrades trust density by demonstrating that coordination infrastructure is perpetually contestable. Conversely, even if Compass loses every case, the multi-front campaign suppresses Forward Integration Score (FIS)—the CDT metric measuring projected coordination capacity under ongoing uncertainty—for all market participants.

I.B. Why Isolation Increases Judicial Burden

Thesis: Separate analyses require courts to repeatedly reconstruct the same economics, increasing error risk while offering no offsetting precision.

Isolated evaluation does not simplify judicial analysis—it complicates it. Each court must independently develop expertise in residential real estate coordination economics. Each court must independently assess whether Compass’s claims reflect genuine competitive harm or strategic rent-seeking. Each court risks reaching conclusions that contradict the other court’s analysis of the same underlying market dynamics.

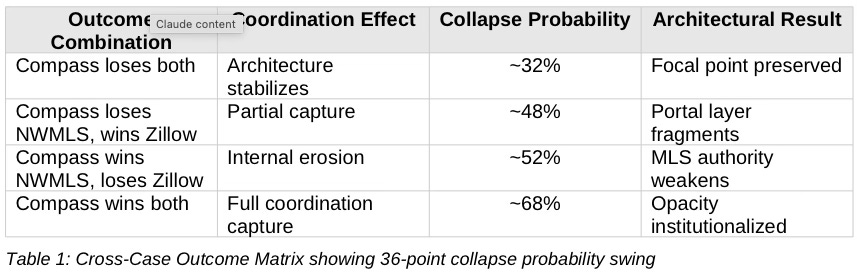

The cross-case outcome matrix from Part IV illustrates the stakes:

A 36-point spread separates best-case (32%) and worst-case (68%) coordination collapse probabilities. Courts evaluating either case in isolation cannot see this spread. The NWMLS court cannot assess how its ruling interacts with potential Zillow outcomes. The Zillow court cannot assess how its ruling interacts with potential NWMLS outcomes. Both courts risk issuing remedies that compound rather than correct coordination harm.

Joint evaluation does not require consolidation or transfer. It requires that courts acknowledge the interdependence of the cases and evaluate remedies with awareness of their cross-case implications. A court granting injunctive relief in one case should consider whether that relief makes sense if the other court reaches a different conclusion.

Insight: Isolated evaluation is not neutral. It systematically advantages the party pursuing fragmentation while disadvantaging parties defending coordination infrastructure. Joint evaluation corrects this procedural asymmetry.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on antitrust law and behavioral economics foresight simulations. See Letter to State Attorneys General on Compass-Anywhere Merger (September 2025), Compass Strategic Forum Shopping Analysis(July 2025), Compass’s Strategic Use the Co-Conspirator Narrative in Antitrust Litigation (Jul 2025), Brief of MindCast AI LLC as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant NWMLS (May 2025), Brief of MindCast AI LLC as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant Zillow (June 2025).

II. Chicago School Foundations—Properly Applied

Thesis: Chicago School Law and Economics already condemns coordination capture when welfare effects are properly specified.

The Modern Chicago School framework does not require doctrinal innovation. It requires doctrinal completion. Ronald Coase, Thomas Schelling, and Gary Becker provided the conceptual architecture; MindCast AI’s National Innovation Behavioral Economics (NIBE) and Strategic Behavioral Coordination (SBC) frameworks provide the measurement infrastructure. Together, they form a predictive discipline capable of modeling platform-era coordination failures before they become irreversible.

II.A. Consumer Welfare Beyond Price

Thesis: Chicago economics focuses on outcomes, not form; in matching markets, welfare depends on search completeness, information integrity, and coordination capacity.

Chicago School antitrust has always been effects-based rather than formalistic. The relevant question is not whether conduct fits a categorical prohibition but whether conduct harms consumer welfare. Robert Bork’s The Antitrust Paradox(1978) established that consumer welfare—not competitor welfare, not structural purity—is the proper objective of antitrust enforcement.

In matching markets, consumer welfare depends on variables that price-focused analysis systematically misses. When buyers cannot find sellers—or cannot trust that their search is complete—welfare losses occur even if nominal prices appear unchanged. Search incompleteness operates as a hidden tax: buyers expend additional time, attention, and risk to approximate full market knowledge. The tax is real even though it does not appear in transaction records.

The Inventory Completeness Ratio (ICR) measures this welfare variable directly. When ICR declines—when active inventory visible through shared coordination infrastructure falls as a percentage of total market activity—matching efficiency degrades regardless of price effects. Buyers miss properties that would have been optimal matches. Sellers receive fewer competing offers than market conditions would support. The welfare loss is structural, not transactional.

Compass’s Private Exclusive program directly reduces ICR. Listings withheld from MLS during initial marketing phases are, by definition, not visible through shared coordination infrastructure. The reduction is measurable, the welfare effect is predictable, and the harm falls on consumers—precisely the outcome Chicago economics exists to prevent.

II.B. Transaction Costs vs. Coordination Costs

Thesis: Transaction costs govern bargaining efficiency; coordination costs determine whether bargaining can occur at all. Platforms primarily affect the latter.

Coase’s 1960 paper ‘The Problem of Social Cost’ demonstrated that private parties bargain to efficient outcomes when transaction costs are low. For sixty years, the Coase Theorem has anchored law and economics: reduce friction—legal fees, search costs, information asymmetries—and efficient allocation follows.

The theorem is correct within its boundary conditions. But those conditions embed a hidden assumption: parties can identify the efficient equilibrium and coordinate toward it. Coase’s canonical examples—the rancher and farmer negotiating over crop damage—involve parties who share stable environments, common problem understanding, and sufficient time to negotiate. The assumption fails in complex, high-velocity systems.

Coordination costs measure whether the bargaining mechanism can engage at all. Three components determine coordination capacity:

Focal Point Availability: Parties need shared reference points—what Schelling called focal points—to converge on ‘obvious’ solutions. Without governance architecture providing these reference points, convergence fails even when both parties prefer agreement.

Narrative Alignment: Parties must agree what they are negotiating about. When organizational identity or strategic frame is contested, no bargaining range exists.

Trust Density: Trust determines how signals are interpreted. High trust means offers are understood as cooperative; low trust means identical signals are read as threats. Below a threshold (~0.40 on the Coordination Stability Score), cooperative bargaining becomes structurally impossible.

MLS systems build coordination capacity through all three mechanisms. Mandatory submission creates a focal point (the shared database where listings appear). Reciprocity rules establish narrative alignment (members contribute inventory in exchange for access to others’ inventory). Professional accountability and dispute resolution maintain trust density. Private Exclusives attack all three mechanisms simultaneously—fragmenting the focal point, contesting the reciprocity narrative, and degrading trust through selective disclosure.

George Akerlof’s ‘The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism’ (1970) provides the canonical economic demonstration of coordination collapse dynamics. Akerlof showed that when buyers cannot distinguish between high-quality goods (’peaches’) and low-quality goods (’lemons’), they discount all goods toward the lemon price. Sellers of peaches withdraw rather than accept lemon prices. The market spirals toward adverse selection until only lemons remain—or until institutional mechanisms (warranties, certifications, reputational intermediaries) restore quality signaling.

The MLS is precisely such an institutional mechanism. Mandatory submission certifies that the shared database is comprehensive—buyers can trust that searching the MLS means searching ‘the market.’ Private Exclusives introduce quality uncertainty: buyers cannot know whether the MLS database is complete or whether superior inventory has been withheld. As Akerlof predicted, rational buyers respond by discounting all MLS-visible inventory, treating the database as potentially incomplete. The discount is not on price but on search confidence—the welfare loss occurs through increased search costs and match inefficiency.

The death spiral Akerlof identified operates through trust density. As Private Exclusives proliferate, trust in database completeness declines. As trust declines, more sellers question the value of full MLS exposure—why submit to a database buyers no longer trust? The Akerlofian feedback loop converts coordination infrastructure into coordination liability. The CDT metric Data Trust Coefficient (DTC) tracks this dynamic: NWMLS maintains DTC of 0.86 under current governance; CDT simulations project DTC declining to 0.52 under mandatory Private Exclusive accommodation—crossing the threshold where quality uncertainty dominates and the lemons equilibrium becomes self-reinforcing.

The analytical distinction is critical: a market can have zero transaction costs and catastrophic coordination costs. Reducing transaction costs while destroying coordination architecture degrades welfare—the opposite of Coasean prediction. Platform conduct that appears to reduce friction may actually raise coordination costs by fragmenting the institutional infrastructure that enables efficient matching.

II.C. Why Modern Platforms Force Doctrinal Clarity

Thesis: Platform design choices redistribute coordination capacity, making institutional architecture a first-order competitive variable.

Pre-platform markets could treat coordination as background condition. Buyers and sellers found each other through classified ads, referrals, and local knowledge. Coordination capacity was distributed across many actors, none of whom could unilaterally fragment it. Antitrust could focus on price and output because coordination was not subject to strategic manipulation.

Platforms change this calculus. When a single platform controls routing decisions for substantial market share, that platform can redistribute coordination capacity by design choice. Routing standards, display priorities, data access rules—these architectural decisions determine which parties can find each other and under what conditions. The decisions are not neutral infrastructure; they are competitive conduct with welfare consequences.

The Compass–NWMLS–Zillow litigation complex illustrates the phenomenon. Compass’s Private Exclusive program is a routing choice: inventory flows through Compass-controlled channels rather than shared MLS infrastructure. Zillow’s Listing Access Standards are a counter-routing choice: inventory must flow through MLS before reaching portal aggregation. The dispute is not about access per se—it is about which routing architecture governs market coordination.

Chicago economics requires courts to evaluate welfare effects. When platform architecture determines coordination capacity, and coordination capacity determines welfare, platform architecture becomes antitrust conduct. Courts need not adopt new doctrine to reach this conclusion—they need only apply existing effects-based analysis to the variables that actually matter in platform markets.

Insight: Chicago School economics is not wrong—it is incomplete without explicit recognition of coordination costs as a welfare variable. Platform markets force the completion by making coordination architecture strategically manipulable.

III. Existing Legal Doctrine That Already Fits

Thesis: Courts possess the doctrinal tools to evaluate coordination-cost harms without doctrinal invention.

The coordination-cost framework does not require courts to create new antitrust law. Existing precedent already addresses joint venture governance, information control, essential facilities, and two-sided markets. What the framework provides is analytical vocabulary that connects these precedents to platform-era coordination problems. The doctrine exists; the application requires extension, not invention.

III.A. Joint Ventures and Anti-Free-Riding Precedent

Thesis: MLS governance fits squarely within joint-venture law permitting proportional rules to preserve shared infrastructure.

The Supreme Court has long recognized that joint ventures may adopt rules necessary to create and maintain their product. In Broadcast Music, Inc. v. CBS (1979), the Court held that blanket licensing arrangements—which facially appeared to fix prices—were procompetitive because they created a product (efficient music licensing) that could not exist without collective action. The relevant inquiry was not whether the arrangement restrained trade in some abstract sense, but whether it enabled output that would otherwise be impossible.

NCAA v. Board of Regents (1984) extended this logic to governance rules. The Court acknowledged that sports leagues require rules—including rules that limit individual member conduct—to produce the cooperative product that generates consumer value. Rules that appear restrictive when viewed in isolation may be essential when viewed as components of a coordination system.

Northwest Wholesale Stationers v. Pacific Stationery (1985) addressed membership rules directly. The Court held that cooperative purchasing arrangements could condition membership on compliance with contribution requirements without triggering per se antitrust liability. The underlying principle: parties who extract value from shared infrastructure may be required to contribute to that infrastructure as a condition of participation.

The most directly applicable Chicago School precedent is Rothery Storage & Van Co. v. Atlas Van Lines, Inc., 792 F.2d 210 (D.C. Cir. 1986). Writing for the court, Judge Robert Bork—whose Antitrust Paradox defined the consumer welfare standard—upheld Atlas Van Lines’ prohibition on its independent agents using their own equipment to move goods outside the Atlas system. The agents argued that Atlas’s ‘vest pocket’ prohibition restrained their competitive freedom. Bork rejected the claim, holding that Atlas could condition participation on rules preventing free-riding on the network’s reputation and shared infrastructure.

The Rothery fact pattern is virtually identical to Compass v. NWMLS. Atlas Van Lines was a network of independent agents (like an MLS) who shared infrastructure and reputation. Independent agents (like Compass) sought to use that shared infrastructure while pursuing independent operations that undermined the network’s value proposition. Bork held that ancillary restraints necessary to preserve network integrity were not antitrust violations but efficiency-enhancing governance.

Rothery explicitly validates mandatory submission rules. An MLS, like Atlas, creates value through shared infrastructure—comprehensive listing data, standardized cooperation protocols, reputational certification. A member who demands access to others’ listings while withholding its own inventory during preferential marketing windows is ‘vest pocketing’ in real estate terms: extracting network value while undermining network integrity. Bork’s analysis confirms that rules preventing such free-riding are lawful ancillary restraints, not horizontal price-fixing or output restrictions.

MLS mandatory submission rules fit squarely within this precedent. The MLS product is market completeness—a comprehensive database of active inventory that enables efficient buyer-seller matching. Market completeness requires contribution. A rule requiring members to submit listings within defined timeframes is analogous to the contribution requirements upheld in cooperative joint ventures: it prevents free-riding that would degrade the shared resource.

Compass demands access to all other members’ listings while withholding its own inventory during initial marketing phases. This is the precise free-riding pattern that joint-venture precedent permits rules to prevent. The mandatory submission requirement does not exclude Compass from competition—it conditions Compass’s access to shared resources on reciprocal contribution to those resources.

III.B. Information Control and Routing as Antitrust Variables

Thesis: Antitrust law already scrutinizes information exchange, timing, granularity, and access—routing standards are functionally equivalent.

Antitrust doctrine has long recognized that information control can constitute competitive conduct. In United States v. Container Corp. (1969), the Supreme Court held that information exchange among competitors could facilitate tacit coordination and harm consumers, even absent explicit price-fixing. The timing, granularity, and scope of information sharing all affect competitive dynamics.

More recent enforcement has extended this logic to platform contexts. The Department of Justice’s challenge to the RealPage rental pricing algorithm rests on the theory that routing rental information through a single platform enabled coordination that harmed consumers. The FTC’s required divestiture in ICE/Black Knight reflected concern that controlling mortgage information flow threatened competition. In both cases, regulators recognized that information routing—not merely information possession—constitutes conduct with competitive consequences.

The CDT framework operationalizes this doctrine through the Disclosure Timing Coherence (DTC) metric. DTC measures alignment between listing disclosure timing and market-wide visibility norms. When disclosure timing diverges—when some inventory becomes visible early to select parties while remaining invisible to the broader market—information asymmetry creates competitive advantage for controllers and welfare loss for participants.

Compass’s Private Exclusives exhibit low DTC (0.34). The program deliberately delays public disclosure to create a window of exclusive visibility. This timing manipulation is functionally equivalent to the information control practices that antitrust doctrine already scrutinizes. The routing choice—through Compass networks rather than MLS—determines who sees what and when. That routing choice is competitive conduct, not neutral design.

III.C. Essential Facilities Logic, Modernized

Thesis: Where visibility and routing are essential to competitive participation, denial or compelled misuse implicates essential-facility principles.

Essential facilities doctrine addresses situations where access to particular infrastructure is necessary for competitive participation. The doctrine has narrow application—Verizon Communications v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko (2004) emphasized that courts should be reluctant to mandate sharing absent clear monopolization. But the doctrine’s underlying logic remains relevant: when infrastructure is essential and denial excludes competition, antitrust may intervene.

The Compass litigation complex presents a mirror-image problem. Compass does not seek access to an essential facility from which it has been excluded. Compass seeks to compel misuse of essential coordination infrastructure—forcing MLS systems to accept delayed submissions and forcing portals to distribute inventory that bypassed coordination requirements.

The essential-facilities logic applies in reverse. If MLS coordination infrastructure is essential to efficient market functioning—and the forty-five trillion dollar residential real estate market suggests it is—then compelled degradation of that infrastructure harms the market participants who depend on it. Zillow’s Listing Access Standards do not deny Compass access to an essential facility; they prevent Compass from using Zillow as a distribution channel for inventory that undermines the coordination infrastructure Zillow’s users depend on.

The remedy Compass requests would transform essential coordination infrastructure into a transmission mechanism for coordination-degrading conduct. This compelled misuse is the harm, not the cure. Courts applying essential-facilities logic should recognize that protecting infrastructure integrity is as important as preventing exclusionary denial.

Insight: Existing doctrine—joint ventures, information control, essential facilities—provides the tools. What courts require is the analytical vocabulary to apply these tools to platform coordination problems. The CDT framework provides that vocabulary.

The doctrinal foundations established, Part V now turns to how coordination harm manifests across the two institutional layers—MLS governance and portal routing—and why attacking both simultaneously produces nonlinear welfare degradation.

IV. The Unified Coordination Harm

Thesis: NWMLS enforcement and Zillow curation protect the same coordination function through different institutional mechanisms.

The analytical error of isolation obscures a structural reality: MLS governance and portal routing standards are complementary components of a single coordination architecture. Internal rules ensure that inventory enters the shared system. External standards ensure that aggregation reflects coordination-compliant inventory. Weakening either layer degrades coordination capacity. Weakening both layers converts shared market infrastructure into a distribution system for opacity.

IV.A. Internal Coordination: MLS Submission and Reciprocity

Thesis: Mandatory submission preserves market completeness and prevents strategic inventory withholding.

MLS mandatory submission rules serve a coordination function that transaction-cost analysis cannot capture. The rules do not merely reduce search costs by aggregating listings in one place. They solve a collective action problem: absent mandatory submission, individual brokers face incentives to withhold inventory for strategic advantage while free-riding on others’ contributions.

The coordination logic is straightforward. Market completeness requires comprehensive inventory visibility. Comprehensive visibility requires contribution from all participants. Voluntary contribution is unstable because withholding creates private advantages (exclusive buyer access, increased double-ending probability) while imposing social costs (reduced matching efficiency, degraded price discovery). Mandatory submission solves this instability by converting contribution from optional to required.

NWMLS exhibits high coordination architecture metrics precisely because its governance enforces this logic. Its Disclosure Timing Coherence (DTC) of 0.86 reflects enforcement that maintains temporal alignment between listing decisions and market visibility. Its Focal-Point Integrity Score (FIS) of 0.98 reflects preservation of the shared reference point where buyers and sellers converge. The metrics are not abstractions—they measure the institutional conditions that enable efficient residential matching at national scale.

IV.B. External Coordination: Portal Routing Standards

Thesis: Platform standards ensure that aggregated visibility reflects coordination-compliant inventory rather than private rails.

Portal routing standards operate at a different layer but serve the same coordination function. Where MLS rules govern inventory entry into the shared system, portal standards govern how that inventory reaches consumers. Zillow’s Listing Access Standards condition display on prior MLS routing—ensuring that the aggregation layer transmits coordination-compliant inventory rather than serving as an alternative channel for coordination bypass.

The Part IV analysis introduced the aggregation-routing distinction. Aggregation reduces search costs by concentrating inventory on fewer platforms. Routing determines which institutional pathway inventory follows to reach visibility. Compass seeks aggregation without routing—portal distribution for listings that bypassed MLS submission. This demand would convert aggregation from coordination reinforcement to coordination degradation.

Zillow’s CSI of 0.58 reflects an institution whose routing standards align with coordination preservation but whose integrity is contingent on maintaining those standards. Compelled transmission of non-compliant inventory would degrade Zillow’s coordination contribution by forcing the platform to relay inventory that deliberately bypassed coordination requirements. The platform would become a distribution mechanism for opacity rather than a coordination-preserving aggregator.

The Supreme Court’s vertical restraint doctrine directly supports Zillow’s routing standards. In Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36 (1977), the Court held that manufacturers (and by extension, platforms) may impose non-price vertical restraints—such as location clauses or quality standards—on distributors to promote interbrand competition, even if those restraints reduce intrabrand competition. The Court recognized that restraints inducing ‘competent and aggressive retailers’ who invest in service quality enhance overall market competition.

GTE Sylvania provides the doctrinal foundation for Zillow’s Listing Access Standards. Zillow competes with other real estate portals (Redfin, Homes.com, Realtor.com) in the interbrand market for consumer attention. Within Zillow’s platform, brokerages compete for visibility—the intrabrand dimension. Zillow’s routing standards may reduce intrabrand competition by excluding non-MLS inventory (Compass’s position), but they enhance interbrand competition by ensuring Zillow’s database maintains the coordination integrity that consumers value.

Under GTE Sylvania, the critical question is whether the vertical restraint promotes competition at the interbrand level—competition between platforms offering differentiated products. Zillow’s Listing Access Standards differentiate Zillow from competitors by guaranteeing consumers access to coordination-compliant, MLS-verified inventory. A portal that displays coordination-bypassing Private Exclusives alongside MLS inventory cannot make that guarantee. Compass seeks to eliminate the very product differentiation that drives interbrand competition, converting all portals into undifferentiated aggregation pipes. This is the harm GTE Sylvania permits platforms to prevent.

IV.C. The Compounding Effect of Dual Relief

Thesis: Weakening both layers converts shared market infrastructure into a distribution system for opacity.

The cross-case outcome matrix reveals that coordination harm compounds rather than adds when both layers are weakened simultaneously. If Compass prevails in NWMLS alone, MLS rules weaken but portals can still condition display on coordination compliance. If Compass prevails in Zillow alone, portals must transmit non-compliant inventory but MLSs can still enforce submission requirements. Either outcome partially preserves coordination architecture.

If Compass prevails in both cases, no constraint remains. MLSs cannot require timely submission. Portals cannot condition display on submission compliance. The coordination architecture that enables efficient matching—the shared focal point, the reciprocity structure, the trust infrastructure—fragments into incompatible visibility channels. The 68% collapse probability in the dual-loss scenario reflects this compounding dynamic.

The CDT simulation models this compounding through the Remedy Sensitivity Gradient (RSG). RSG measures how marginal legal interventions affect coordination capacity. In the dual-relief scenario, RSG spikes as the remaining constraints on coordination bypass disappear. The gradient is nonlinear—removing the second constraint causes more damage than removing the first because no fallback mechanism remains.

Insight: Internal rules and external standards are not redundant—they are complementary. Weakening either layer partially degrades coordination; weakening both layers eliminates the institutional architecture that enables efficient matching.

The coordination harm is now established. The next question is evidentiary: what proof demonstrates that Compass’s conduct produces the harms described? Remarkably, Compass has provided that proof itself.

V. The Dispositive Economic Admission

Thesis: Compass’s own pleadings collapse its antitrust narrative across both cases.

Compass’s complaints contain an admission that, properly understood, defeats its antitrust theory as a matter of law. The company alleges that Private Exclusives can yield approximately 2.9 percent higher prices for sellers. This figure appears in both the NWMLS complaint and the Zillow complaint. Compass presents it as evidence that Private Exclusives provide seller value.

Under Ohio v. American Express Co. (2018), platforms operating in two-sided markets cannot demonstrate antitrust injury by showing harm to one side alone. The Court held that credit card networks connect merchants and cardholders in a way that requires analysis of effects on both sides. Real estate markets exhibit the same two-sided structure: platforms connect sellers (through listings) with buyers (through search). Any analysis of competitive effects must account for impacts on both groups.

V.A. The 2.9% Private-Exclusive Price Effect

Thesis: A seller uplift necessarily implies buyer harm in a two-sided market.

The arithmetic is inescapable. Higher seller prices are, by mathematical identity, higher buyer costs. On Seattle’s median home price of approximately $850,000, a 2.9 percent premium represents roughly $24,650 transferred from buyers to sellers—and, through increased double-ending rates, to Compass’s commissions.

This transfer does not reflect efficiency gains. Private Exclusives do not reduce transaction costs, improve matching quality, or increase housing supply. The premium reflects information asymmetry: sellers (through their agents) capture value by restricting buyer competition during initial marketing phases. Fewer competing buyers means less price discipline. The 2.9 percent premium is the measured cost of that reduced competition.

The structural mechanism deepens the harm. Private Exclusives remove the market signals that discipline price discovery: days on market, price reduction history, comparable exposure. Buyers cannot know whether a property’s price reflects market clearing or information asymmetry. The pricing premium is not incidental—it is structural. Private Exclusives are designed to extract value by suppressing competition among buyers.

Under AmEx, this admission should be dispositive. Compass cannot demonstrate net welfare gain when its own pleading establishes that the challenged conduct transfers wealth from buyers to sellers through information suppression. The 2.9 percent figure is not ambiguous evidence requiring expert interpretation—it is Compass’s own quantification of the buyer harm its program creates.

V.B. Why the Admission Travels Across Forums

Thesis: Courts cannot credit the same price effect as procompetitive in one case and anticompetitive in another without incoherence.

The 2.9 percent admission creates cross-case vulnerability that isolated evaluation obscures. In the NWMLS case, Compass argues that mandatory submission rules harm competition by preventing sellers from capturing this premium. In the Zillow case, Compass argues that routing standards harm competition by preventing distribution of listings that generate this premium. Both arguments treat the premium as procompetitive value that rules and standards improperly suppress.

But under two-sided market analysis, the premium is buyer harm—not seller benefit. Rules and standards that prevent the premium do not suppress procompetitive value; they prevent wealth extraction through information asymmetry. Compass cannot argue in one forum that restricting Private Exclusives harms sellers while arguing in another that the restriction protects buyers, because the same 2.9 percent figure underlies both claims.

Courts evaluating either case must eventually confront this arithmetic. The NWMLS court must ask: does mandatory submission harm competition by preventing a 2.9 percent wealth transfer from buyers to sellers? The Zillow court must ask: do routing standards harm competition by preventing distribution of listings designed to extract that transfer? Both questions have the same answer: conduct that generates buyer harm through information suppression is not procompetitive, regardless of which forum evaluates it.

Insight: The 2.9% admission is legally dispositive under AmEx two-sided market analysis. Compass’s own pleading establishes buyer harm that its antitrust claims cannot overcome. Joint evaluation makes this dispositive effect visible across both cases.

VI. Joint Evaluation as a Doctrine-Reducing Move

Thesis: Evaluating the cases together simplifies, rather than complicates, antitrust analysis.

Joint evaluation might appear to increase judicial burden by requiring courts to consider conduct beyond the immediate parties. The opposite is true. Joint evaluation reduces analytical complexity by aligning with Chicago School insistence on parsimony and effects-based reasoning. One theory, one set of effects, one remedy analysis—rather than two parallel analyses that reach potentially inconsistent conclusions.

VI.A. One Theory, One Set of Effects, One Remedy Analysis

Thesis: Duplicative proceedings waste judicial resources while increasing the probability of inconsistent outcomes.

Isolated evaluation requires each court to independently reconstruct residential real estate coordination economics. The NWMLS court must develop expertise in MLS functions, focal-point dynamics, and coordination costs. The Zillow court must develop the same expertise, applied to portal routing. Both courts evaluate the same 2.9 percent price effect without coordinated analysis of its implications.

Joint evaluation consolidates this analytical work. A single theory—coordination capture degrades consumer welfare—explains both sets of claims. A single set of effects—focal-point fragmentation, buyer harm through information asymmetry, trust erosion—predicts outcomes across both cases. A single remedy analysis—preserve coordination architecture, prevent compelled degradation—applies to both defendants.

Chicago School economics has always favored parsimony. Bork’s consumer welfare standard replaced multi-factor balancing tests with a unified objective. Posner’s economic analysis of law replaced formalistic categories with effects-based inquiry. Joint evaluation continues this tradition by applying unified analysis to conduct that pursues a unified strategy through multiple legal vehicles.

VI.B. Avoiding Inconsistent Injunctions

Thesis: Isolated remedies risk neutralizing each other while amplifying harm.

Remedies designed in isolation may interact in unpredictable ways. An NWMLS injunction weakening mandatory submission would increase inventory available for Private Exclusive routing. A Zillow injunction compelling transmission of Private Exclusives would provide distribution for that inventory. Neither injunction alone produces the full coordination harm—but together they eliminate the complementary constraints that preserve market coordination.

Alternatively, remedies might neutralize each other. A court might craft NWMLS relief assuming portal standards remain in place, while another court crafts Zillow relief assuming MLS rules remain in place. Both remedies depend on constraints the other remedy weakens. The result is neither the coordination preservation both courts intended nor the coordination capture Compass sought—but something worse: unpredictable fragmentation with no institutional actor positioned to restore order.

Joint evaluation enables remedy design that accounts for cross-case interactions. Courts can condition relief on the other case’s outcome. Courts can coordinate remedy timing to prevent gaming. Courts can ensure that whatever emerges—coordination preservation or coordination restructuring—reflects deliberate choice rather than procedural accident.

Insight: Joint evaluation is not a departure from Chicago School principles—it is their application. Parsimony favors unified analysis of unified conduct. Effects-based reasoning requires considering how remedies interact. Isolated evaluation is the departure.

VII. Precedent the Courts and Agencies Can Set

Thesis: Courts and the DOJ/FTC can articulate narrow, transferable precedent recognizing coordination capacity as a protected competitive dimension.

The Compass litigation complex presents an opportunity for doctrine formation. Courts can recognize coordination capacity as a competitive variable without expanding antitrust liability. Agencies can issue guidance that clarifies when platform routing or governance conduct raises coordination-cost concerns. The precedent would be narrow enough to provide predictability and broad enough to transfer to future platform disputes.

VII.A. Judicial Holding (Minimalist)

Thesis: Platform curation and joint-venture governance that preserve coordination capacity are presumptively procompetitive absent proof of net welfare loss.

A minimalist judicial holding would establish that conduct preserving coordination infrastructure warrants rule-of-reason analysis rather than per se condemnation, and that plaintiffs challenging such conduct bear the burden of demonstrating net welfare harm across all affected market participants.

Applied to the NWMLS case: mandatory submission rules are coordination-preserving governance that plaintiffs must prove cause net welfare harm. Compass’s own 2.9 percent admission establishes buyer harm, shifting the burden back to Compass to demonstrate offsetting efficiencies. Under AmEx two-sided analysis, this burden cannot be met.

Applied to the Zillow case: routing standards conditioning display on MLS submission are coordination-preserving curation that plaintiffs must prove cause net welfare harm. Compass seeks compelled transmission of inventory designed to extract buyer surplus. The requested remedy is the harm, not the cure.

The holding requires no new doctrine. It applies existing rule-of-reason analysis with explicit recognition that coordination capacity is a welfare-relevant variable. Courts already consider output, price, and quality effects; coordination capacity affects all three in matching markets.

VII.B. Agency Guidance (Administrable)

Thesis: Regulators can issue guidance clarifying when platform routing or governance shifts raise coordination costs and harm consumers.

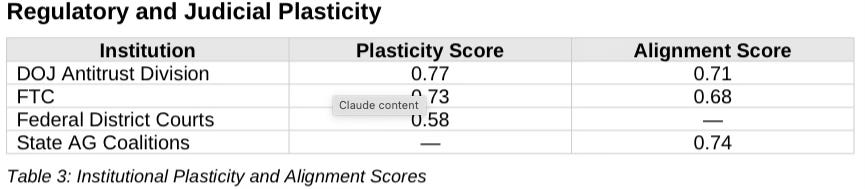

The DOJ and FTC can issue guidance without waiting for litigation outcomes. Such guidance would identify coordination-cost factors relevant to platform antitrust analysis:

1. Inventory completeness: Does the conduct reduce the percentage of market activity visible through shared coordination infrastructure?

2. Disclosure timing: Does the conduct create information asymmetries through delayed or selective disclosure?

3. Focal-point integrity: Does the conduct fragment the shared reference point where market participants converge?

4. Trust density: Does the conduct degrade the trust infrastructure that enables cooperative market behavior?

5. Two-sided effects: Does claimed benefit to one side of the market come at the expense of the other side?

Guidance framed in these terms would provide market participants with predictability, reduce litigation costs by clarifying analytical frameworks, and position agencies to intervene efficiently when coordination-cost harms emerge. The CDT metrics developed in this series operationalize each factor, making guidance administrable rather than merely aspirational.

Insight: Courts can set narrow precedent; agencies can issue administrable guidance. Together, they can establish coordination capacity as a recognized competitive dimension without expanding antitrust liability beyond existing doctrinal boundaries.

VIII. Implications Beyond Real Estate

Thesis: Coordination-cost antitrust generalizes to any platform market built on aggregation, matching, and trust.

The coordination-cost framework extends beyond residential real estate to any market where aggregation produces value, matching efficiency determines welfare, and trust enables cooperative behavior. Digital marketplaces, labor platforms, and ad-tech exchanges all exhibit these characteristics. Precedent established in the Compass litigation complex would transfer to future platform disputes.

VIII.A. Digital Marketplaces and Ad Tech

Thesis: Information routing control determines competitive access.

Digital marketplaces connect dispersed buyers and sellers through platform infrastructure. When platforms control routing decisions—which listings appear prominently, which buyers see which inventory, which sellers reach which audiences—routing becomes competitive conduct. The coordination-cost framework provides analytical vocabulary for evaluating when routing choices preserve versus degrade market coordination.

Ad-tech exchanges exhibit similar dynamics. Information about user attention, advertiser demand, and publisher inventory flows through intermediary platforms. Routing decisions—which advertisers see which inventory, which publishers access which demand—determine competitive outcomes. Conduct that fragments coordination infrastructure for private advantage harms the market participants who depend on that infrastructure.

VIII.B. Labor Platforms and Marketplaces

Thesis: Coordination degradation masquerades as ‘disintermediation.’

Labor platforms present coordination-cost dynamics with particular clarity. Platforms connecting workers with employers produce value through matching efficiency. When platform conduct fragments the labor market—creating parallel pools of workers and jobs that cannot find each other—coordination costs rise even if transaction costs fall.

The rhetoric of ‘disintermediation’ often obscures coordination capture. Platforms claiming to remove middlemen may actually be replacing one coordination architecture with another—one that the platform controls and can manipulate for private advantage. The coordination-cost framework enables evaluation of whether claimed disintermediation actually improves matching efficiency or merely redistributes coordination rents.

Insight: The Compass litigation complex is a test case. Precedent established here will shape antitrust analysis of platform coordination across markets. Courts and agencies should craft holdings with this transferability in mind.

IX. Conclusion—The Modern Chicago School

Thesis: Chicago School antitrust remains correct, but incomplete without explicit recognition of coordination economics.

The Modern Chicago School of Law and Economics does not reject the Chicago tradition—it completes it. Coase identified that transaction costs determine whether private bargaining reaches efficient outcomes. The coordination-cost extension recognizes that efficient bargaining also requires coordination capacity: the ability of dispersed parties to find each other, establish common expectations, and converge on efficient matches.

Four propositions emerge from Part V’s integrated analysis:

Coordination capture is condemned regardless of wrapper. Whether conduct attacks coordination through internal governance challenges (NWMLS) or external platform demands (Zillow), the harm is the same. The legal vehicle does not determine the competitive effect.

Platform architecture is economic conduct. Routing decisions, display standards, and data access rules are not neutral infrastructure—they determine coordination capacity and therefore affect consumer welfare. Antitrust analysis must evaluate these architectural choices.

Joint evaluation is analytically superior. Isolated evaluation of unified strategy produces analytical error and remedial incoherence. Parsimony—the Chicago School virtue—favors one theory, one set of effects, one remedy analysis.

Courts can set precedent without abandoning doctrine. Existing law on joint ventures, information control, and two-sided markets provides the tools. What the coordination-cost framework provides is the vocabulary to apply those tools to platform-era problems.

The Compass–NWMLS–Zillow litigation complex presents a bounded opportunity. Courts can recognize that coordination capacity is a competitive variable worth protecting. Agencies can issue guidance that identifies coordination-cost factors in platform analysis. Both can establish precedent that transfers to the broader platform economy.

The alternative is fragmentation by default. Courts evaluating cases in isolation will reach inconsistent conclusions. Remedies designed without cross-case awareness will interact in unpredictable ways. Coordination architecture will erode not through deliberate choice but through procedural accident.

The analytical framework exists. The CDT metrics operationalize coordination capacity as a measurable variable. The legal doctrine fits. The question is whether courts and regulators will deploy the framework before coordination harm becomes irreversible.

Insight: Chicago School antitrust correctly rejected formalism for effects-based analysis. The Modern Chicago School extends that analysis to coordination effects—the welfare variables that dominate platform markets. The extension is completion, not departure.

Appendix: CDT Metric Definitions Reference

Causal Integrity Metrics

Action–Language Integrity (ALI): Measures alignment between stated procompetitive justifications and observed conduct. Screens pretextual efficiency claims under rule-of-reason analysis. Range: 0–1.0.

Cognitive–Motor Fidelity (CMF): Measures whether actions actually implement the claimed economic logic. Distinguishes ancillary restraints from naked coordination capture. Range: 0–1.0.

Resonance Integrity Score (RIS): Measures trust, adoption coherence, and network stability over time. Maps directly to output preservation in network and matching markets. Range: 0–1.0.

Causal Signal Integrity (CSI): Measures the trustworthiness of claimed causal links after adjusting for noise, incentives, and disclosure timing. CSI failure predicts false-positive antitrust intervention if claims are credited. Range: 0–1.0.

Coordination Architecture Metrics

Disclosure Timing Coherence (DTC): Measures alignment between listing disclosure timing and market-wide visibility norms. Low DTC predicts buyer-side welfare loss through search incompleteness. Range: 0–1.0.

Inventory Completeness Ratio (ICR): Measures the percentage of active market inventory visible through shared coordination infrastructure. Declining ICR predicts price dispersion, reduced match quality, and trust erosion. Range: 0–1.0.

Focal-Point Integrity Score (FIS): Indicates how well an entity preserves or distorts MLS visibility norms. Low FIS destabilizes the shared reference point underlying real estate coordination. Range: 0–1.0.

Coordination Capacity Index (CCI): Composite of RIS, DTC, ICR, and routing neutrality. Primary welfare output variable under all remedy scenarios. Range: 0–1.0.

Institutional Plasticity Metrics

Institutional Update Velocity (IUV): Measures how quickly an institution revises its analytical framework when presented with new economic evidence. Range: 0–1.0.

Incentive Alignment Index (IAI): Measures alignment between institutional incentives and consumer-welfare outcomes. Range: 0–1.0.

Narrative Reorganization Score (NRS): Measures the institution’s ability to coherently integrate new concepts without doctrinal rupture. High plasticity predicts where precedent will crystallize first. Range: 0–1.0.

System-Level Metrics

Coordination Stability Score (CSS): Measures trust density and structural stability. Below ~0.40, cooperative market behavior becomes structurally impossible. Range: 0–1.0.

Remedy Sensitivity Gradient (RSG): Measures how marginal legal interventions affect coordination capacity. Identifies injunctions that overshoot and induce systemic harm. Range: varies by context.

Interpretive Summary

Compass: ALI: Low | CMF: Low | RIS: Low | CSI: Fails gating threshold. Conduct monetizes coordination scarcity rather than efficiency. Litigation substitutes for market competition. Stated consumer-welfare justifications diverge materially from observed incentive gradients toward visibility capture and coordination bypass.

NWMLS: ALI: High | CMF: High | RIS: High | CSI: Passes. Governance rules causally preserve market completeness and output. High causal coherence: enforcement actions track directly to preservation of market completeness. Exhibits alignment between mission, rules, and enforcement.

Zillow: ALI: Medium–High | CMF: Medium | RIS: Medium | CSI: Conditional. Platform integrity preserved under current standards; degrades under compelled transmission of opaque inventory. Occupies intermediate position: platform standards align with coordination preservation but vulnerable to compelled-transmission remedies.

Key Finding: Agencies adapt faster than courts (plasticity scores 0.73–0.77 vs. 0.58). Courts require litigant-supplied frameworks to update doctrine. The most likely entry point for coordination-cost precedent is judicial reasoning that explicitly cites agency-framed concepts around platform information architecture. All regulators show receptivity to joint-evaluation frameworks when framed as error-reduction tools rather than theory expansion.

Appendix: Foresight Scenario Synthesis

Scenario A: Isolated Remedies Granted

Coordination capacity degrades across both institutional layers

Search incompleteness becomes systemic as inventory fragments

Litigation proliferates across markets as precedent encourages coordination attacks

Collapse probability: ~68%

Scenario B: Joint Evaluation, Remedies Denied

Coordination architecture preserved in both layers

MLS–portal complementarity maintained and strengthened

Litigation incentives diminish as coordination-attack strategy fails

Collapse probability: ~32%

Scenario C: Joint Evaluation with Narrow Safe Harbor (Most Stable)

Courts recognize coordination-preserving governance and routing as presumptively procompetitive

Disclosure timing elevated as a welfare variable in platform analysis

Narrow, transferable precedent established for platform markets

Collapse probability: ~35% with stable equilibrium

Assessment: Scenario C represents the most stable outcome—preserving coordination architecture while establishing precedent that transfers to future platform disputes. The scenario requires courts to recognize coordination capacity as a competitive variable and to evaluate the Compass litigation complex as a unified strategic assault on that capacity.

Final Insight: Across all CDT flows, results converge: coordination capacity is the scarce competitive resource, and Compass’s conduct targets its privatization. Joint evaluation is not merely analytically superior—it is causally necessary to avoid false positives and welfare-reducing remedies. This litigation complex presents a credible, bounded opportunity for courts and regulators to formalize coordination-cost economics within the Modern Chicago School of Law and Economics.