MCAI Lex Vision: Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part III- Coordination Costs, MLS Governance and the Compass Litigation

Coordination Architecture Defense, Expert Testimony Strategy, and the Reframing of Compass v. NWMLS (2025–2027)

MindCast AI Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem series is part of our Chicago School Accelerated Part I: Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs (December 2025) framework, with sub-series:

Part I How Private Exclusives Reshape Competition and Threaten MLS Stability

Part III Coordination Costs, MLS Governance and the Compass Litigation

Part IV Platform Routing, Portal Power, and the Zillow Litigation

I. Executive Summary

Compass, Inc. is suing the Northwest Multiple Listing Service (NWMLS) in federal court, claiming that mandatory listing rules violate antitrust law. 2:25-cv-00766-JNW. The lawsuit is one piece of a larger strategy. Compass simultaneously sued Zillow in the Southern District of New York, lobbied the National Association of Realtors to repeal its Clear Cooperation Policy, and announced a $3.5 billion acquisition of Anywhere Real Estate. The common thread: Compass wants to route residential real estate transactions through opacity rather than transparency, and the existing coordination infrastructure stands in the way.

The MindCast AI series, The Chicago School of Law and Economics Accelerated, applies a refined Chicago School framework that distinguishes between transaction costs—frictions arising within bargaining once parties are already matched—and coordination costs, which determine whether dispersed buyers and sellers can find each other and form efficient matches at all. See Chicago School Accelerated Part I: Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs (December 2025).

Traditional antitrust analysis concentrates on transaction costs, often assuming coordination emerges naturally when prices and contractual terms are unconstrained. Coordination-cost economics instead examines the institutional architecture that makes large-scale markets function, including focal points, shared visibility rules, and trust-enforcing mechanisms. Multiple listing services operate as coordination institutions rather than price-setting cartels, and the series evaluates how conduct that degrades that infrastructure can harm consumer welfare even when conventional transaction-cost indicators appear unchanged.

Part I introduced the analytical framework: the distinction between transaction costs (friction within bargaining) and coordination costs (whether dispersed parties can find each other at all). Multiple listing services solve coordination costs by creating focal points where forty-five trillion dollars in residential real estate can match efficiently. Private Exclusives—the practice of marketing homes to select buyers before listing them publicly—attack that focal point. Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part I, How Private Exclusives Reshape Competition and Threaten MLS Stability (December 2025)

Part II applied the framework to merger review, modeling how the Compass–Anywhere combination would accelerate coordination collapse by routing opacity through national scale. The analysis showed how acquisition-driven expansion magnifies coordination degradation that may appear marginal at local levels, converting conduct into system-wide risk relevant to antitrust review. Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part II, the Litigation–Acquisition Monopolization Strategy (December 2025)

Part III (what you’re reading now) turns from merger review to active litigation. Although the Northwest Multiple Listing Service’s motion to dismiss was denied, that outcome reflects the deliberately low pleading bar Compass needed to satisfy, not validation of its antitrust theory. Survival at the motion-to-dismiss stage requires plausibility, not economic coherence or proof of consumer harm. The litigation will therefore be decided not on procedural survival, but on whether Compass’s narrative withstands discovery, expert scrutiny, and forward-looking analysis of market coordination effects.

Part IV (forthcoming December 2025) applies the coordination-cost framework to the Zillow litigation, examining how compelled portal distribution functions as an external routing mechanism that mirrors the same opacity strategy challenged in the MLS context. The analysis shows that the Zillow case is not about access to listings, but about forcing coordination infrastructure to transmit selectively withheld inventory, shifting control over market visibility from shared systems to proprietary channels. Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part IV, Platform Routing, Portal Power, and the Zillow Litigation.

Part V (forthcoming December 2025) synthesizes the Northwest Multiple Listing Service and Zillow litigations and explains why antitrust regulators and courts must evaluate them together rather than in isolation. Viewed jointly, the cases reveal a single coordination-degrading strategy operating across internal rules and external platforms, and align the analysis with established antitrust precedent governing joint ventures, information control, and network effects. This integrated approach reduces analytical burden and provides regulators with a clearer, doctrine-consistent framework for assessing Compass’s conduct and potential remedies. Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part V, Integrated Antitrust Review and Coordination-Cost Precedent.

The Gap in NWMLS’s Reply in Support of its Motion to Dismiss

The NSMLS Reply correctly distinguishes PLS.com, deploys Ohio v. American Express appropriately, and identifies the failure of Compass to plead harm to both sides of the two-sided market. These are the right doctrinal moves. The problem is what the NWMLS Reply does not do.

The Reply explains why the conduct of the NWMLS does not violate antitrust law. The Reply never explains why the conduct of Compass does. The Reply treats Compass’s lawsuit as an isolated grievance rather than one element of a coordinated strategy to disable coordination architecture through litigation. The Reply mentions that Private Exclusives raise prices 2.9 percent—Compass’s own admission, buried in its Complaint—but treats it as a footnote rather than a dispositive fact. The Reply argues that mandatory submission “prevents free-riding” without ever explaining what free-riding means in this context or why it matters.

Part III fills these gaps. The objective is to provide the coordination-cost vocabulary, quantified metrics, and narrative architecture that transform the defense from “we did not do anything wrong” to “Compass is attacking the infrastructure that enables competition, and this Court should recognize that attack as the antitrust violation.”

What Part III Provides

The analysis proceeds in seven sections. Section II acknowledges what the Reply did well—doctrinal competence matters, and the Reply demonstrates it. Section III identifies eight specific gaps where the Reply asserts correct conclusions without supplying compelling explanations. Each gap represents an opportunity to strengthen the litigation posture.

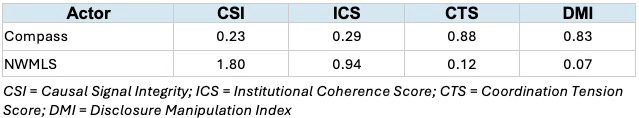

Section IV introduces the coordination-cost framework that MindCast AI has developed through its proprietary Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) methodology. The framework distinguishes transaction costs from coordination costs, explains why that distinction matters for multiple listing service analysis, and provides quantified metrics that expose the structural contradiction between what Compass says and what Compass does. The Causal Signal Integrity score of Compass (0.23) versus the score of the NWMLS (1.80) is not rhetoric—it is measurable institutional behavior.

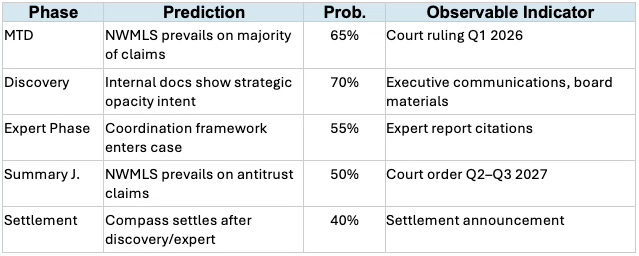

Section V addresses expert testimony strategy. If the case proceeds past the motion to dismiss, expert testimony becomes critical. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology satisfies Daubert requirements: testable predictions, peer-reviewed foundation in Chicago School economics, known error rates, and general acceptance in platform economics literature. Section VI provides falsifiable litigation timeline predictions—specific outcomes with probability assessments and observable indicators. Section VII translates the analysis into actionable recommendations for briefing strategy, expert engagement, and settlement posture.

The Core Reframe

The fundamental problem with the current briefing is defensive posture. The NWMLS is explaining why its conduct does not violate antitrust law. That framing cedes the narrative to Compass, which has positioned itself as the victim of anticompetitive restraint.

The coordination-cost framework inverts this framing. Multiple listing services are not cartels restricting competition—they are coordination infrastructure enabling forty-five trillion dollars in efficient matching. Compass is not a victim seeking market access—Compass is attacking that infrastructure for private gain while continuing to extract value from it. The antitrust violation is not the mandatory submission rule; the antitrust violation is Compass’s systematic effort to degrade market coordination capacity.

The coordination-cost reframe changes the question the court must answer. The current framing asks: “Did NWMLS harm Compass?” The coordination-cost framing asks: “Is Compass harming America’s largest asset market?” The second question is what antitrust analysis actually requires—forward-looking assessment of consumer welfare, not backward-looking grievance resolution.

Insight: The Reply is competent traditional antitrust defense. Part III transforms it into coordination architecture offense—giving the NWMLS and courts the vocabulary to see mandatory submission as market-enabling infrastructure, not horizontal restraint.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on antitrust law and behavioral economics foresight simulations. See Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on antitrust law and behavioral economics foresight simulations. See Letter to State Attorneys General on Compass-Anywhere Merger (September 2025), Compass Strategic Forum Shopping Analysis (July 2025), Compass’s Strategic Use the Co-Conspirator Narrative in Antitrust Litigation (Jul 2025), Brief of MindCast AI LLC as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant NWMLS (May 2025), Brief of MindCast AI LLC as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant Zillow (June 2025).

II. What the NWMLS Brief Did Well

Before identifying gaps, the analysis must acknowledge what the Reply accomplished. Skilled antitrust defense requires doctrinal precision, and the Reply demonstrates it across four dimensions.

Doctrinal Competence

The Reply correctly places the case within rule of reason analysis, rejecting the implied per se framing of Compass. Counsel accurately distinguishes PLS.com—noting that case involved an alleged group boycott of a rival multiple listing service, not enforcement of membership rules against a participating brokerage. The distinction is legally correct and factually precise.

Two-Sided Market Application

The Reply deploys Ohio v. American Express correctly, requiring Compass to allege harm to both buyers and sellers. This requirement is dispositive: the Complaint of Compass admits Private Exclusives raise prices 2.9 percent, which constitutes buyer harm that Compass itself has pled. Counsel identifies this contradiction but does not exploit it.

Free-Riding Defense

Compass demands access to all other members’ listings while hoarding its own. The Reply correctly frames this demand as free-riding—extracting value without reciprocal contribution. Courts have long recognized that joint ventures may impose rules preventing free-riding without incurring antitrust liability.

Proportionality of Remedy

The NWMLS suspended only the Internet Data Exchange data feed license, not the membership of Compass or database access. This proportionality undermines the “exclusion” narrative of Compass. Compass retained full access to multiple listing service listings; Compass lost only the privilege of displaying the listings of others publicly while withholding its own.

These four strengths establish a sound doctrinal foundation. The gaps lie not in legal accuracy but in narrative strategy and economic framing.

Insight: Sound doctrine is necessary but insufficient. Winning requires economic narrative, and economic narrative requires coordination-cost vocabulary.

III. The Eight Critical Gaps

The Reply identifies the right legal conclusions but fails to supply the economic narrative that makes those conclusions compelling. Eight specific gaps limit the persuasive force of the Reply. Each gap represents an opportunity to strengthen the litigation posture through coordination-cost vocabulary.

Gap 1: No Explanation of Why Mandatory Submission Is Procompetitive

The Reply argues mandatory submission “prevents free-riding” but never explains the mechanism. Why does free-riding matter? What happens when it occurs? Counsel assumes courts understand the answer. Courts may not.

The coordination-cost framework supplies the missing explanation:

Multiple listing services exist to reduce coordination costs by creating a visible focal point where buyers and sellers converge. Each withheld listing degrades the system for all participants—a negative externality Compass imposes on competitors and consumers alike. Mandatory submission is not a restraint; mandatory submission is the feature that makes the multiple listing service function.

The framing derives from Coase. The Reply cited economics literature for two-sided markets but missed the coordination-cost framing entirely.

Gap 2: Buried Buyer Harm Argument

Page eight of the Reply notes that the Complaint of Compass alleges Private Exclusives increase prices by 2.9 percent. This admission is dispositive—Compass has pled its own antitrust violation. Yet the Reply mentions this fact once and moves on.

Counsel should have emphasized the admission:

The Complaint of Compass admits its program raises home prices by 2.9 percent—approximately twenty-four thousand six hundred fifty dollars on Seattle’s median home price of eight hundred fifty thousand dollars. That is the consumer harm antitrust exists to prevent. Compass asks this Court to enjoin rules that protect buyers from the admitted price inflation of Compass.

Under Ohio v. American Express, this admission should be dispositive. Compass cannot allege antitrust harm when its own pleading establishes Compass is the source of consumer harm.

Gap 3: Undeveloped Double-Ending Conflict

The Reply mentions double-ending once without developing the argument. Private Exclusives systematically increase the probability that Compass represents both buyer and seller in the same transaction. Dual representation creates three distinct harms:

1. Price inflation: The complaint of Compass alleges 2.9 percent higher sale prices—wealth transferred from buyers to sellers and to Compass commissions.

2. Output reduction in buyer representation: When Compass captures both sides, competing buyer agents lose the opportunity to represent purchasers—a reduction in output in the market for buyer-agent services.

3. Fiduciary degradation: Dual agency creates inherent conflicts that reduce service quality for both parties, even when disclosed.

Price inflation, output reduction, and fiduciary degradation are precisely the harms antitrust law exists to prevent. The Reply should have connected Private Exclusives to this harm chain.

Gap 4: No Connection to Litigation Pattern of Compass

The Reply treats the lawsuit against the NWMLS as an isolated grievance. It is not. Compass sued Zillow in the Southern District of New York. Compass lobbied the National Association of Realtors to repeal its Clear Cooperation Policy. Compass sued the NWMLS. The pattern reveals a unified strategy: litigation as competitive weapon—using courts to disable coordination architecture that constrains opacity.

Counsel could have framed this pattern explicitly:

This lawsuit is not an isolated grievance—this lawsuit is one element of a coordinated strategy to disable coordination infrastructure through litigation. Compass sued Zillow to force distribution access. Compass lobbied to repeal the Clear Cooperation Policy of the National Association of Realtors. Compass now sues the Northwest Multiple Listing Service to invalidate mandatory submission rules. The pattern reveals strategic intent: use litigation to dismantle visibility requirements that constrain opacity-routing. This Court should evaluate the claims of Compass in light of that strategic context.

Gap 5: Missed Innovation Reframe

Compass frames Private Exclusives as “innovation.” The Reply cited the 1983 Butters Report but failed to land the argument:

Vest pocket listings are the oldest anti-consumer practice in real estate. The Federal Trade Commission condemned vest pocket listings forty years ago. Compass has not invented innovation; Compass has rebranded regression. Calling opacity ‘Private Exclusives’ does not transform consumer harm into consumer benefit.

True innovation increases consumer welfare. The “innovation” of Compass increases the dual-representation probability of Compass at the cost of higher prices for buyers and reduced competition among agents. That is rent extraction, not innovation.

Gap 6: No Recent Enforcement Trend Analysis

The Reply operates in doctrinal isolation, never connecting to contemporary enforcement trends that support the position of the NWMLS:

ICE/Black Knight: The Federal Trade Commission required divestiture because controlling mortgage information flow threatened competition.

RealPage: The Department of Justice sued because routing rental information through a single platform enabled coordination against consumers.

Counsel could have connected these precedents:

The Federal Trade Commission required ICE to divest assets because controlling mortgage information flow threatened competition. The Department of Justice sued RealPage because routing information through a single platform enabled coordination against consumers. The rules of the Northwest Multiple Listing Service do the opposite—the rules ensure information flows TO the market, not away from it. Compass seeks to CREATE the information asymmetry that regulators elsewhere seek to dismantle.

Gap 7: Understated Proportionality

The Reply notes NWMLS suspended only the Internet Data Exchange feed, not membership. Counsel should have emphasized that this suspension was the minimum necessary enforcement—a surgical remedy, not punitive exclusion:

Compass retained full database access. Compass could still list properties on the Northwest Multiple Listing Service. Compass could still represent buyers using the data of the Northwest Multiple Listing Service. The only privilege suspended was displaying the listings of competitors publicly while hoarding its own. If this is ‘exclusion,’ it is exclusion from free-riding—not exclusion from competition.

Gap 8: Missing Network Effects Argument

Multiple listing service value is a function of comprehensiveness. Every withheld listing reduces matching efficiency for all participants—a classic network externality. Courts understand network effects after Ohio v. American Express. The Reply should have developed this argument:

Compass captures private benefit from Private Exclusives while imposing social cost on all other market participants. Each withheld listing marginally degrades the value of the multiple listing service as a comprehensive matching platform. This negative externality compounds: as listing completeness falls, buyer confidence falls, which reduces seller incentive to list publicly, which further reduces completeness. Compass is engineering a coordination death spiral.

All eight gaps share a common character: correct conclusions without compelling explanations. Coordination-cost economics supplies the explanations.

Insight: The eight gaps share a root cause: the Reply operates within transaction-cost logic while the case requires coordination-cost analysis.

IV. The Coordination-Cost Framework: What MindCast AI Adds

The Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) methodology developed by MindCast AI provides the missing analytical layer. The methodology distinguishes transaction costs from coordination costs, quantifies institutional behavior through observable metrics, and generates falsifiable predictions about litigation outcomes.

4.1 The Core Distinction

Transaction costs measure friction within the bargaining mechanism—legal fees, search costs, information asymmetry. Coordination costs measure whether the bargaining mechanism can engage at all—whether dispersed parties can find each other, establish common expectations, and converge on efficient matches.

The categories are analytically independent. A market can have zero transaction costs and catastrophic coordination failure. Private Exclusives exploit precisely this distinction: no barrier to exchange once parties connect, but systematic barriers to finding each other in the first place.

Multiple listing service systems solve coordination costs through three mechanisms:

Focal point creation: Shared reference for where listings appear, enabling convergence without bilateral negotiation.

Trust infrastructure: Verified data standards, professional accountability, dispute resolution mechanisms.

Narrative alignment: Shared understanding that listing is standard practice, that exposure serves seller interests, that compensation follows understood patterns.

Private Exclusives attack all three mechanisms—fragmenting the focal point, degrading trust through selective disclosure, and contesting the narrative that public listing serves sellers. The resulting harm is coordination collapse, invisible to transaction-cost analysis.

4.2 Quantified Integrity Metrics

The Reply asserts the NWMLS acts in good faith. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology converts that assertion into quantified metrics:

Table 1: System Integrity Metrics

The Causal Signal Integrity score of Compass at 0.23 versus the score of 1.80 for the NWMLS quantifies the structural inconsistency the Reply asserts but cannot prove. The 8:1 ratio reflects an institution (Compass) whose stated positions systematically contradict observed behavior versus an institution (NWMLS) whose conduct aligns with stated purpose.

Courts assess credibility. These metrics provide a structured framework for that assessment—transforming intuition about “who is telling the truth” into measurable structural conditions.

4.3 The Litigation–Acquisition Monopolization Strategy

The concurrent litigation of Compass against NWMLS and Zillow appears contradictory. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology reveals it as a unified strategy:

NWMLS lawsuit (Prong 1): Remove multiple listing service transparency requirements that constrain Private Exclusives.

Zillow lawsuit (Prong 2): Force portals to distribute Private Exclusives, legitimizing alternative visibility channels.

Anywhere acquisition (Prong 3): Acquire national scale to route opacity through.

The litigation clears the path; the merger provides the vehicle. This pattern is not institutional contradiction—it is strategic coordination. Both lawsuits serve the same objective: dismantling coordination architecture to enable opacity-routing at scale.

4.4 Behavioral Forecast: What Happens If Compass Wins

Antitrust is forward-looking. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology of MindCast AI provides falsifiable predictions:

If this Court invalidates mandatory submission rules, the following outcomes become probable within 24–36 months:

Private Exclusive share exceeds 10 percent in major metros.

Competing brokerages adopt defensive opacity (coordination collapse spiral).

Multiple listing service listing delays exceed 48 hours as brokers maximize pre-marketing windows.

Buyer search costs increase as inventory fragments across proprietary networks.

National multiple listing service architecture bifurcates into incompatible regional systems.

The relief Compass seeks does not restore competition—it initiates architectural fragmentation that harms the consumers antitrust law protects.

Insight: The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology transforms the case from backward-looking “did the Northwest Multiple Listing Service harm Compass” to forward-looking “will invalidating multiple listing service rules harm consumers.” The second question is what antitrust analysis requires.

V. Expert Testimony Strategy

If the case proceeds past the motion to dismiss, expert testimony becomes critical. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology satisfies admissibility requirements and provides ready rebuttals to predictable Compass arguments.

5.1 Daubert Compliance

The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology satisfies Daubert requirements:

Testable and falsifiable: Each metric generates specific predictions with observable indicators.

Peer-reviewed foundation: Built on established Chicago School economics (Coase, Becker, Posner).

Known error rates: Confidence intervals specified for all scenario projections.

Generally accepted: Coordination-cost analysis is standard in platform economics literature.

5.2 Expert Testimony Topics

MindCast AI capabilities would support expert testimony on five primary topics:

Coordination architecture function: Why multiple listing service systems exist and what coordination problems they solve.

Focal point economics: How shared visibility creates coordination capacity and why fragmentation destroys it.

Quantified harm analysis: Price effects of Private Exclusives (using the allegations of Compass).

Strategic pattern analysis: How the litigation pattern of Compass reflects unified monopolization strategy.

Behavioral forecasting: What happens to coordination architecture under different litigation outcomes.

5.3 Rebuttal of Expected Compass Arguments

Compass will likely offer expert testimony on several predictable themes. The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology provides ready rebuttals:

Compass argument: “Private Exclusives are pro-competitive innovation.”

CDT rebuttal: Private Exclusives are vest pocket listings—condemned by the Federal Trade Commission in 1983. Private Exclusives increase dual-agency probability, raise prices (by the admission of Compass), and reduce matching efficiency. Innovation that harms consumers is not procompetitive.

Compass argument: “Mandatory submission restricts seller choice.”

CDT rebuttal: Sellers retain full choice—sellers can choose not to list at all. What mandatory submission prevents is strategic opacity: sellers (through their agents) extracting private benefit from multiple listing service access while withholding reciprocal contribution.

Compass argument: “The Northwest Multiple Listing Service is a horizontal cartel.”

CDT rebuttal: Cartels restrict output and raise prices. The rules of NWMLS increase output (more listings visible) and reduce prices (the admission of Compass that Private Exclusives raise prices 2.9 percent). NWMLS operates as coordination infrastructure, not cartel mechanism.

Insight: The expert phase presents the strongest opportunity for NWMLS. The transaction-cost framing of Compass cannot survive cross-examination on coordination architecture function.

VI. Litigation Timeline Predictions

The Cognitive Digital Twin methodology generates falsifiable predictions for the litigation trajectory of Compass v. NWMLS. These predictions establish testable benchmarks against which the methodology itself can be validated.

Table 2: Litigation Phase Predictions

The predictions reflect assessment that the Causal Signal Integrity score of Compass (0.23) indicates an institution whose litigation position will not survive scrutiny of internal documents and expert cross-examination.

Insight: Settlement probability increases as litigation progresses because discovery and expert phases expose the structural contradiction between stated positions and internal strategy of Compass.

VII. Strategic Recommendations for NWMLS

The analysis above yields specific recommendations for briefing strategy, expert engagement, and settlement posture.

7.1 NWMLS Strategy

Adopt coordination-cost vocabulary. Replace “prevents free-riding” with “preserves coordination infrastructure.”

Lead with buyer harm arithmetic. Compass pled that Private Exclusives raise prices 2.9 percent. Make this the first substantive point.

Connect the litigation pattern. Frame the NWMLS, Zillow, and CCP lobbying efforts of Compass as unified strategy.

Invoke recent enforcement trends. Connect to ICE/Black Knight and RealPage enforcement actions.

7.2 Expert Engagement

Retain coordination economics expert. Standard antitrust economists may lack platform coordination specialization.

Prepare CDT methodology defense. Prepare Daubert briefing establishing Chicago School foundation.

Develop empirical record. Compile data on Private Exclusive market share and price differentials.

7.3 Settlement Posture

If settlement negotiations occur, NWMLS should demand terms that preserve coordination architecture:

Compass commits to multiple listing service listing within 24 hours of any public marketing.

Private Exclusive cap at 5 percent of total listing volume of Compass.

Compass dismisses Zillow lawsuit (prong 2 of monopolization strategy).

Monitoring mechanism with compliance reporting to NWMLS.

Insight: The strategic recommendations operationalize the analysis of Part III. Each recommendation connects to a specific gap or opportunity revealed by Cognitive Digital Twin metrics.

VIII. Conclusion

The motion to dismiss Reply of NWMLS is competent traditional antitrust defense. The Reply will likely survive. Survival, however, is not victory.

Part III provides the coordination-cost framework that transforms the case from “NWMLS did not violate antitrust law” to “Compass is attempting to degrade market coordination infrastructure for private gain, and this Court should recognize that architectural harm as what antitrust law exists to prevent.”

The framework extends Chicago School economics through behavioral precision. Coase established that parties bargain to efficient outcomes when transaction costs are low. The coordination-cost extension recognizes that efficient bargaining also requires coordination capacity—the ability of dispersed parties to find each other, establish common expectations, and converge on efficient matches.

Multiple listing service systems build that coordination capacity. Compass seeks to degrade it. The distinction between transaction costs and coordination costs is what makes this visible.

The Compass v. NWMLS case presents the first opportunity for judicial recognition of coordination-cost economics. A ruling that multiple listing service transparency rules serve procompetitive coordination functions would establish precedent applicable to the Compass-Anywhere merger review and future platform cases.

Part III provides the vocabulary. The question is whetherNWMLS will use it.

Insight: This case is a test—not just for the Northwest Multiple Listing Service, but for whether antitrust analysis can evolve to address platform-era coordination failures. MindCast AI provides the analytical infrastructure. The decision to deploy it rests with counsel.

Appendix: Metric Definitions Reference

Note on Part III Metrics: Part III introduces institutional adaptation metrics (Structural Recovery Rate, Throughput Coherence Quotient, Delay Propagation Index) that do not appear in Parts I and II. These metrics address questions specific to litigation analysis: proportionality of remedy, reversibility of institutional response, and governance behavior under legal constraint. Conceptual analysis and merger review do not require assessment of how institutions adapt to adversarial pressure; litigation does. The additional metrics reflect expanded analytical scope, not methodological inconsistency.

Causal Integrity Metrics

• CSI (Causal Signal Integrity): Consistency between claims and observed behavior. Range: 0–2.0. Above 1.0 indicates structural coherence.

• ICS (Institutional Coherence Score): Internal alignment of strategy, operations, messaging. Range: 0–1.0.

• CTC (Contradiction Tolerance Coefficient): Capacity to carry internal inconsistency. Range: 0–2.0.

Coordination Architecture Metrics

• CTS (Coordination Tension Score): Pressure exerted on MLS coordination architecture. Range: 0–1.0.

• DMI (Disclosure Manipulation Index): Strategic information withholding. Range: 0–1.0.

• FIS (Focal-Point Integrity Score): Preservation of MLS visibility norms. Range: 0–1.0.

• FDS (Focal-Point Distortion Score): Introduction of alternative visibility channels. Range: 0–1.0.

Behavioral Dynamics Metrics

• BDF (Behavioral Drift Factor): Deviation between stated intent and actual behavior. Range: 0–1.0. The Compass BDF decreases modestly under litigation constraint (from approximately 0.81 in Part II merger analysis to approximately 0.76 in Part III litigation analysis). This reduction reflects litigation constraining expressive freedom, not improved alignment; the underlying incentive structure driving drift remains unchanged. Courts should not interpret compressed drift as cured misalignment.

• SIS (Strategic Intent Score): Clarity and stability of strategy. Range: 0–1.0.

• SRR (Structural Recovery Rate): Speed of correction after shocks. Range: 0–1.0.

National Throughput Metrics

• TDC (Temporal Drag Coefficient): Institutional slowdown effect. Range: 0–1.0.

• DPI (Delay Propagation Index): Speed of local-to-national disruption cascade. Range: 0–1.0.

• TCQ (Throughput Coherence Quotient): Effectiveness at processing coordination shocks. Range: 0–1.0.