MCAI Economics Vision: Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics Analysis of Real Estate Buyer Bans and the Price of Scarcity

Why Corporate Home‑Purchase Restrictions Miss the Real Drivers of Housing Affordability

On January 21, 2026, President Trump signed an Executive Order restricting institutional purchases of single-family homes. This action activates the policy condition analyzed in the foresight simulation below. The order alters buyer eligibility but does not modify the supply-side constraints (zoning, permitting, and approval timelines) that govern housing price formation. The foresight analysis therefore shifts from conditional to observational: the mechanisms identified can now be evaluated against real-world behavioral response.

In early January 2026, President Donald Trump announced plans to bar large institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes, claiming the move would expand access for individual buyers and alleviate the nation’s housing affordability crisis. Trump Blindsides Wall Street Allies With Crackdown on Housing Investors, Wall Street Journal (Jan 9, 2026). Headlines highlighted the proposal’s political salience, noting stock market reactions and mixed expert reactions on its effectiveness. Housing economists cautioned that such a ban, by itself, would not address the underlying shortage of available homes or the structural delays in permitting and construction that drive price rigidity, characterizing the policy as popular but insufficient in solving deep supply constraints.

I. Introduction: Scarcity, Not Buyer Identity

Housing affordability debates often collapse into narratives about who is buying homes rather than why prices continue to rise. A MindCast AI Chicago School of Law and Behavioral Economics perspective begins from a different premise: prices reflect scarcity shaped by institutional constraints and predictable behavioral responses to those constraints. Chicago School Accelerated — The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics, Why Coase, Becker, and Posner Form a Single Analytical System (December 2025);

As Milton Friedman observed, “The price system is a mechanism for communicating information” (Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom, 1962), but Chicago behavioral analysis extends that insight by asking how agents interpret, adapt to, and strategically respond to those signals over time. Housing prices therefore communicate not only supply-side dysfunction, but also institutional learning failures and incentive misalignment.

MindCast AI’s Chicago School of Law and Behavioral Economics is not a static equilibrium framework. It treats law, regulation, and market structure as behavior-shaping architectures that condition incentives, adaptation speed, and substitution pathways. Price theory, transaction-cost economics, public choice, and coordination economics operate alongside behavioral response modeling that measures how real actors reroute capital, delay action, or exploit rule boundaries when friction rises. Corporate participation in housing markets emerges as a behavioral response to inelastic supply and regulatory delay, not as an exogenous distortion.

The analysis therefore evaluates proposed corporate home-purchase bans through a dual Chicago lens: classical causal mechanisms and behavioral adaptation. Each section pairs doctrinal and economic reasoning with foresight simulations that treat institutions, capital, and households as adaptive decision systems with incentives, constraints, and update velocities. Metrics are not forecasts in isolation; they are behavioral stress tests designed to produce falsifiable probability bands tied to observable triggers.

Methodological Note: Foresight Simulations and Behavioral Measurement

The analysis draws on MindCast AI foresight simulations, which operationalize the Chicago School of Law and Behavioral Economics by modeling institutions, capital providers, and households as adaptive decision systemsresponding to legal, regulatory, and market incentives over time. The simulations evaluate how agents update behavior under constraint, including substitution pathways, coordination failure, enforcement saturation, and institutional learning delays.

Internal Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) architectures, metric-routing logic, and validation thresholds are not reproduced in this publication. Instead, the paper reports simulation-derived behavioral patterns, probability bands, and falsification triggers that are relevant for policy analysis and empirical verification. This separation preserves analytical clarity while ensuring that predictions remain grounded in observable mechanisms rather than proprietary system design.

The analysis operates as a foresight simulation by modeling how a housing system evolves under constraint, rather than by issuing numerical forecasts. The paper traces how institutional frictions, incentive structures, and behavioral responses interact once a buyer-ban policy enters an already supply-constrained market, identifying which outcomes become structurally likely and which outcomes become unavailable. Dominant constraints are isolated, adaptive pathways are mapped, and observable indicators are specified that would confirm or falsify those pathways over time. Foresight, in this framework, consists of anticipatory structural reasoning—revealing future behavior implied by present conditions rather than asserting point predictions.

II. Market Price Formation Under Supply Constraints

Housing prices rise when demand meets binding supply constraints, especially in markets governed by restrictive zoning, extended permitting timeliness, discretionary review processes, and litigation risk. Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics treats these institutional bottlenecks as first-order price drivers because they convert housing into an administratively rationed asset rather than a competitively supplied good. Lengthy approval timelines raise carrying costs, deter smaller builders, and bias production toward higher-end units that can absorb regulatory delay. In Chicago terms, these frictions shift the supply curve upward and inward, while leaving the demand curve largely intact.

To quantify the weight of these institutional bottlenecks, consider the current capital environment. As of January 11, 2026, the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate stands at approximately 6.18%. Political rhetoric often treats this borrowing cost as the primary affordability constraint. Empirical permitting economics reveals a more aggressive driver: regulatory delay (Glaeser & Gyourko 2003; Glaeser, Gyourko & Saks 2005; MindCast AI, Municipal Permitting Economics & Friction Metrics). Quantitative analysis of municipal approval processes shows that each month of permitting delay imposes an effective “friction tax” of approximately 95 basis points per month on housing projects.

When expressed on an annualized basis, administrative delay operates as an implicit cost of roughly 11.4% per year, nearly double prevailing market mortgage rates. For a developer, a four-month discretionary delay is not a scheduling inconvenience; it is economically equivalent to a sudden and permanent doubling of the cost of capital. This compounding scarcity multiplier ensures that even a complete elimination of institutional demand would leave the underlying cost of housing production fundamentally distorted by the administrative state.

Permitting and zoning delays also create temporal scarcity. Projects that take years to clear approvals respond slowly to demand shocks, causing prices to spike rather than quantities to adjust. In markets with inelastic supply, price absorbs the shock almost entirely. Jurisdictions with comparable population growth therefore diverge sharply on affordability outcomes based on approval speed and predictability rather than buyer composition.

Table 1. Capital Cost vs. Regulatory Friction

III. Capital Substitution and Regulatory Arbitrage

Rational capital adapts predictably to regulatory constraints. When policymakers prohibit one ownership form, capital reallocates through alternative legal and financial structures that preserve economic exposure. Limited liability companies, partnerships, nominee buyers, option contracts, seller financing, and rent-to-own arrangements function as close substitutes. As Gary Becker demonstrated, individuals respond to incentives across domains (Becker, The Economic Approach to Human Behavior, 1976), and capital responds to regulatory constraints by finding the lowest-cost path around them. Chicago analysis treats these adjustments as foreseeable behavioral responses rather than loopholes.

In practice, bans on acquisition tend to accelerate substitution toward mezzanine debt, equity-sharing contracts, and rent-to-own structures that preserve exposure while shifting risk to households. These substitutions often raise the cost of capital for households. Institutional buyers typically provide the lowest-cost, most transparent capital due to scale, diversification, and regulatory oversight. Removing these participants shifts financing toward less efficient or less regulated channels, increasing interest rates, fees, and contractual complexity for end buyers.

IV. Transaction Costs and Market Frictions

Buyer-form bans introduce compliance uncertainty, enforcement ambiguity, and litigation risk. These frictions raise transaction costs for sellers, lenders, and developers, which markets then capitalize into prices and rents. Ronald Coase’s insight applies directly: market exchange requires discovery, verification, contracting, and enforcement (Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” 1960). Buyer bans multiply each of these costs. Coasean reasoning predicts that higher transaction costs reduce allocative efficiency even when intentions are redistributive.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. Recent publications:

V. Access to Housing for Private Buyers

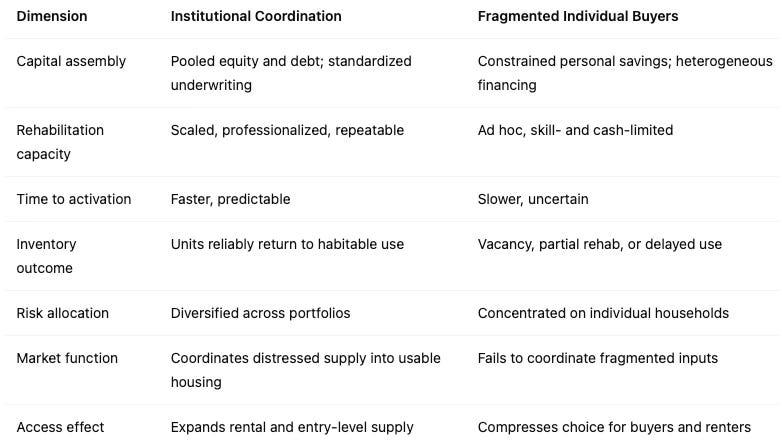

Access to housing depends on purchasing power, inventory availability, financing conditions, and coordination across fragmented actors. Chicago coordination economics emphasizes that markets often fail not because of insufficient capital, but because no single actor can efficiently assemble distressed assets, financing, rehabilitation, and disposition into usable housing stock. Institutional buyers frequently perform this coordination function at scale, particularly in entry-level and previously underutilized housing segments.

Rehabilitation of aging or distressed homes illustrates this mechanism. Individual buyers often lack the capital, risk tolerance, or expertise to acquire properties requiring significant upfront investment before occupancy. Institutional participants aggregate these risks, deploy standardized rehabilitation processes, and return units to market as either sale-ready homes or rental inventory. Removing this coordination service can leave properties vacant, delay reactivation, or shift them to smaller flippers operating with higher margins and less transparency.

A buyer ban therefore risks reducing effective inventory even when headline competition appears to fall (Lambie-Hanson, Li & Slonkosky 2022).

Table 2. Coordination vs. Fragmentation in Entry-Level Housing

VI. Fair Housing Implications and Distributional Effects

From a Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics perspective, equity is measured by its effect on the margin of choice available to constrained participants. Recent proposals to ban corporate home purchases illustrate how political framing can obscure economic mechanisms by casting housing access as a conflict between people and institutions while overlooking how institutional capital structures choice within the Single-Family Rental market.

Fair housing analysis focuses on outcomes rather than stated intent. Buyer-form restrictions risk disparate impacts by increasing rents, reducing entry-level inventory, and favoring sophisticated actors capable of restructuring ownership. These effects disproportionately burden younger households and households of color who rely on rental channels to access higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

Institutional participation also plays a distinct role in rehabilitating distressed housing and supplying rentals in areas with stronger school districts and employment access. Restricting this channel may reduce rental availability in precisely the neighborhoods fair-housing policy seeks to open.

VII. Administrability and Institutional Capacity

Effective housing policy requires administrable rules that courts and agencies can enforce consistently. Ownership form is infinitely malleable. Defining and policing corporate ownership across trusts, partnerships, family offices, and nominee structures imposes monitoring demands that exceed institutional capacity. These costs do not remain administrative abstractions; markets capitalize them into prices.

Public choice theory sharpens the diagnosis. Incumbent homeowners maximize asset value and status-quo certainty. Direct supply restriction through zoning fights is politically costly. Corporate buyer bans function as a low-cost moral proxy for preserving scarcity, allowing exclusionary outcomes to be pursued under populist rhetoric.

VIII. Chicago-Consistent Policy Alternatives

Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics emphasizes interventions that address scarcity directly while remaining neutral to ownership form. Policy effectiveness depends on magnitude, not symbolism. Supply elasticity reforms—by-right zoning, ministerial approvals, and accelerated permitting—dominate buyer restrictions because they remove compounding delay costs embedded in housing production.

Liquidity-preserving mechanisms stabilize supply across cycles by reducing builder risk. Demand-side tools operate effectively only after supply responsiveness improves.

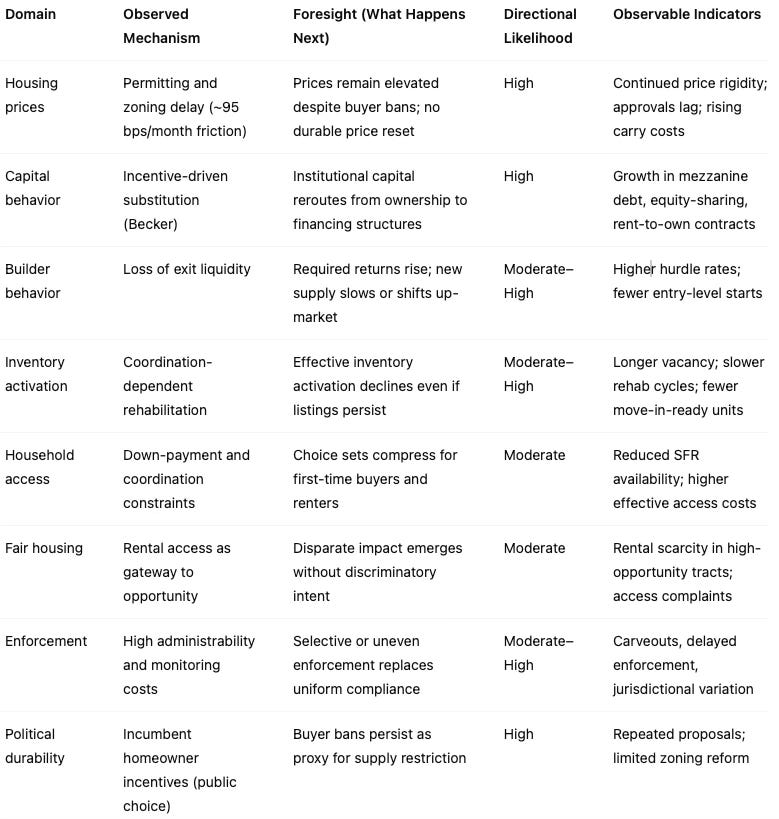

Foresight Summary: What the Analysis Anticipates

The table below consolidates the foresight offered across the paper. Each entry links an observed mechanism to the expected future behavior under a buyer-ban regime, clarifying what is likely to occur, why it occurs, and how it would be empirically observable. This summary is not a set of point forecasts; it is a map of conditional outcomes derived from structural constraints and behavioral adaptation.

Table 3. Consolidated Foresight from the Analysis

IX. Conclusion: Mechanism Over Optics

Corporate home-purchase bans offer political clarity but limited economic effect. Chicago analysis predicts minimal price relief, weak access gains, and material risks to fair housing outcomes. Housing affordability improves through structural expansion, not buyer exclusion.

Sources

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press (1962).

Friedman’s price-system framework underpins the paper’s rejection of buyer-identity explanations for housing prices. His analysis clarifies that prices transmit information about scarcity and constraints, not moral characteristics of market participants. The paper extends this insight by examining how institutional frictions distort those signals.

Becker, Gary S. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. University of Chicago Press (1976).

Becker’s incentive-based model provides the behavioral foundation for capital substitution and regulatory arbitrage. The analysis relies on Becker’s insight that actors re-optimize predictably when constraints change, explaining why buyer bans redirect capital rather than eliminate it. This logic grounds the substitution pathways described in Section III.

Coase, Ronald H. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (1960).

Coase’s transaction-cost framework explains why administrability and enforcement complexity directly affect market outcomes. The paper applies Coase to show how buyer bans multiply contracting, monitoring, and verification costs that markets then capitalize into prices. This forms the core of the transaction-cost analysis in Section IV.

Glaeser, Edward L. & Joseph Gyourko. “The Impact of Building Restrictions on Housing Affordability.” FRBNY Economic Policy Review (2003).

Glaeser and Gyourko provide empirical evidence that land-use regulation and approval delays, not demand composition, drive housing price escalation. Their work supports the paper’s supply-curve emphasis and the claim that zoning and permitting function as first-order price determinants. Section II builds directly on this insight.

Glaeser, Edward L., Joseph Gyourko & Raven Saks. “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in Housing Prices.” Journal of Law and Economics 48(2) (2005).

This study demonstrates how regulatory constraints create persistent price premiums in high-demand cities by suppressing supply responsiveness. The paper uses this work to reinforce the concept of temporal scarcity and the compounding effects of approval delay. It provides empirical grounding for the 95 bps/month friction argument.

Fischel, William A. The Homevoter Hypothesis. Harvard University Press (2001).

Fischel explains how incumbent homeowners act as rational political agents who favor policies that protect property values. The paper draws on this framework to explain why corporate buyer bans function as politically palatable proxies for supply restriction. Section VII’s public-choice analysis relies on this logic.

Lambie-Hanson, Lauren, Wenli Li & Michael Slonkosky. “Institutional Investors and the U.S. Housing Recovery.” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper 22-10 (2022).

This paper documents the role institutional investors played in stabilizing housing supply and reactivating distressed inventory after the financial crisis. The analysis uses these findings to support the coordination argument in Section V, showing how institutional participation can expand effective inventory rather than crowd out households.

MindCast AI: Municipal Permitting Economics & Friction Metrics (Nov 2025)

This research introduces the quantitative framework underlying the 95 basis points per month permitting-delay metric. It translates approval time into an explicit cost variable that functions as a supply-side scarcity multiplier. Section II relies on this metric to compare regulatory friction with market interest rates.

MindCast AI CodeVision: The Chilling Effect of Land-Use Codes (Apr 2025)

CodeVision provides the diagnostic basis for understanding how opaque land-use rules suppress housing activation through uncertainty and delay. The paper uses this work to justify by-right zoning and ministerial approvals as first-order policy responses. It supports the policy hierarchy outlined in Section VIII.