MCAI Lex Vision: HB 2512 and the Collapse of Compass's Coordinated Opposition

The House Hearing Compass Didn't Win

Companion study to: Washington’s SB 6091 and Private Real Estate Market Control (Jan 2026), The Compass Astroturf Coefficient at the Washington State Senate (Jan 2026), Compass–Anywhere, When Scale Becomes Liability (Jan 2026), Windermere and Compass, Two Philosophies of Real Estate (Jan 2026), Compass vs. SB 6091, Narrative Pre-Installation and the Infrastructure of Exception Capture (Jan 2026), How Compass’s State Legislative Testimony Undermined its Federal Antitrust Claims (Jan 2026), The Collapse of Compass’s Co-Conspirator Theory (Jan 2026), Compass vs. Competition: The Case for SB 6091 / HB 2512 Without an Opt-Out Exception (Feb 2026).

Compass’s opposition collapsed not because its witness argued poorly, but because its model depends on volume where enforcement committees demand mechanisms.

Prior MindCast AI publications documented Compass’s three-tier public affairs apparatus: VoterVoice for grassroots manufacturing, compass-homeowners.com for consumer framing, and coordinated testimony for legislative delivery. Compass vs. SB 6091, Narrative Pre-Installation and the Infrastructure of Exception Capture , The Compass Astroturf Coefficient at the Washington State Senate .

The January 28, 2026 House Consumer Protection & Business Committee hearing revealed a fourth tier — activated when the third tier fails. When coordinated testimony collapsed under committee scrutiny, the remaining function was record inflation: documenting nominal opposition without exposing additional witnesses to the questions that damaged the sole testifier. Astroturfing and ghost panels are not random tactics; they are the apparatus in retreat. Volume substitutes for argument when argument fails.

I. What This Publication Does

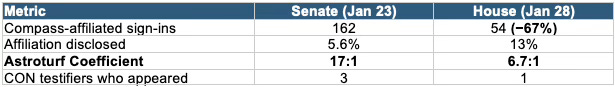

MindCast AI has now published five analyses on Washington’s real estate transparency legislation. The prior four documented Compass’s three-tier public affairs apparatus, the balance-sheet pressure driving its need for exclusive listings, and the 17:1 astroturf coefficient at the January 23 Senate hearing. The present publication analyzes what happened when that apparatus met the House Consumer Protection & Business Committee on January 28 — and why the mobilization collapsed.

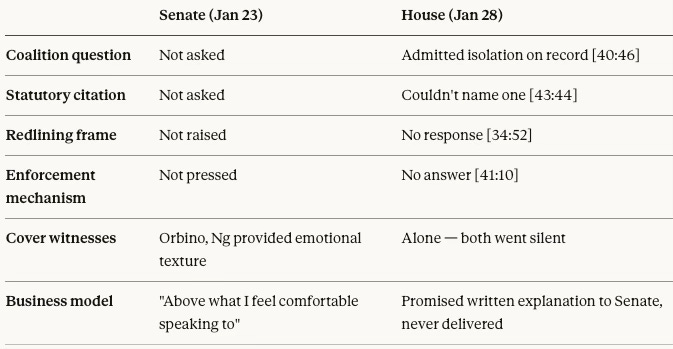

The House hearing diverged sharply from the Senate. Committee members asked different questions, the witness pool shrank by two-thirds, and Compass’s sole testifier faced pointed scrutiny she could not answer. Representatives extracted three admissions the Senate did not obtain: that Compass stands isolated from its own trade association, that Compass Managing Director Huff cannot cite the statutes she claims already address fair housing concerns, and that the opt-out amendment contains no mechanism to detect discriminatory intent.

Notably, Compass Regional VP Cris Nelson was signed in and present for both this hearing and the Jan 23 Senate hearing, yet she declined to testify in either chamber. By repeatedly delegating to Huff—despite Huff’s documented struggle to reconcile the "Private Exclusive" model with fair housing standards—Nelson maintained a persistent executive buffer, shielding senior leadership from the public record across the entire legislative lifecycle.

The Senate passed SB 6091 on January 30 with two amendments — neither of which included the opt-out provision Compass sought. The House can follow that precedent on February 3. The hearing record — documented below — supports that outcome.

Prior MindCast AI publications provide the foundation for cross-chamber comparison. Senate hearing analysis and astroturf methodology appear at The Compass Astroturf Coefficient at the Washington State Senate; the three-tier apparatus documentation appears at Compass vs. SB 6091, Narrative Pre-Installation and the Infrastructure of Exception Capture .

II. The Mobilization Collapse

Astroturfing requires sustained coordination. When participation drops 67% between chambers while concealment rates remain constant, the pattern reveals mobilization fatigue rather than behavioral reform. Compass signed in 162 participants at the Senate hearing; only 54 appeared for the House. Agents who remained continued using identical concealment methods — blank organization fields, ‘Washington Realtor’ labels while voting against the association’s PRO position, credential-stacking without employer disclosure. Washington’s Committee Sign-In system records intent to testify; actual testimony is determined solely by the hearing transcript.

Live testimony collapsed even more dramatically than sign-in volume. At the Senate, Compass fielded three speakers — Brandi Huff (disclosed), Jennifer Ng (undisclosed senior-care frame), and Michael Orbino (inversion frame positioning Compass as consumer protector). At the House, only Huff appeared. Michael Orbino signed in and received an invitation to the Zoom room but did not speak. Chair Wallen called six additional CON sign-ins to testify; none responded.

The Baptist-and-Bootlegger structure—where sympathetic third-party witnesses supply moral justification while a profit-seeking firm captures the economic upside—that gave Senate testimony emotional texture disappeared entirely, leaving Huff as a corporate island.

Cross-Chamber Compass Mobilization Decline: 67% participation drop, sustained concealment

Improved astroturf coefficients reflect attrition, not reform. Compass’s grassroots manufacturing infrastructure generated diminishing returns between chambers — volume without influence, coordination without conversion. The apparatus could fill sign-in sheets but could not fill witness chairs.

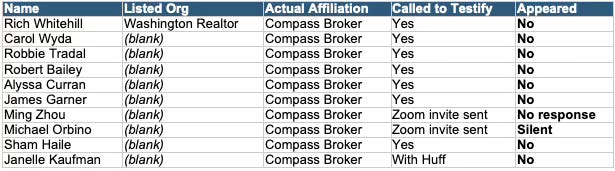

The Ghost Panel: Tactical Retreat Under Fire

Beyond the Compass 67% sign-in decline, a second collapse occurred within the testifying pool itself. Ten individuals signed up to testify CON — explicitly requesting speaking time — then failed to appear when called. All ten are verified Compass brokers. Nine concealed their affiliation on sign-in sheets, listing either ‘Washington Realtor’ or leaving the field blank. These agents declined to testify once committee questioning signaled heightened scrutiny.

Orbino’s silence is the strategic tell. Five days earlier, he delivered a Senate CON testimony — the ‘elderly sellers’ and ‘divorcees’ frame that created momentary committee pause. His disappearance from House testimony, despite signing in, indicates coordinated withdrawal of the human-shield narrative once committee hostility became apparent.

The Ghost Panel achieved its tactical objective: inflating opposition count on the official record without exposing additional witnesses to the scrutiny that damaged Huff. But the tactic is now visible. Ten Compass brokers signed up to testify, concealed their affiliation, and went silent when called. The hearing record documents not just what was said, but who refused to say it.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. We specialize in complex litigation, antitrust, federalism and national innovation policy.

III. The Credibility Failures

Where the mobilization collapse revealed coordination fatigue, the testimony itself revealed preparation gaps. The House committee extracted admissions the Senate did not reach. Senate questioning exposed the business-model vulnerability (’But without the amendments?’ → ‘That is probably above what I feel comfortable speaking to’). House questioning went further — exposing coalition isolation, legal overreach, and enforcement deficiency. These were not gotcha moments; they were straightforward questions a prepared witness should have anticipated.

A. The Isolation Trap

Representative Reeves opened with a question that forced Huff to acknowledge Compass’s isolation from its own industry. The exchange took seconds and produced an on-the-record admission that the state association — to which Compass agents belong — supports the bill Compass opposes. [40:46]

Rep. Reeves [40:46]: “So the Washington Realtors as an association have signed in in favor of the bill, but your firm Compass is opposed — is that right? And you’re a Washington Realtor?”

Huff [40:46]: “That is correct.”

Every subsequent reference to ‘our real estate community’ now carries an asterisk. Compass does not speak for the community; Compass speaks against the community’s stated position. The 47 agents who signed in CON while labeling themselves ‘Washington Realtor’ voted against their association’s unanimous legislative committee decision — a fact now embedded in the hearing record.

B. The Legal Bluff

Huff repeatedly claimed that existing law already addresses fair housing concerns, making the bill redundant. Representative Santos called the bluff by asking for the citation. [43:44]

Rep. Santos [43:44]: “Would you be kind enough to just let us know where in the current statutes the state protections are that you keep referencing? You say that it’s also covered in the state law. I’m asking where?”

Huff [44:16]: “The Attorney General probably is a better person to speak to that than I am.”

A witness who asserts legal sufficiency should be able to cite the law. Huff could not. The deflection to the Attorney General — who had just testified that the AG’s office has concerns about the bill’s enforcement mechanism, not that existing law is sufficient — compounded the credibility damage. The ‘existing law covers it’ argument collapsed under a single follow-up question.

C. The Enforcement Gap

Representative Reeves then pressed on the core weakness of the opt-out amendment: it contains no mechanism to detect discriminatory intent operating behind a privacy rationale. Huff’s response — that agents ‘educate clients’ — describes disclosure, not enforcement. [41:10]

Rep. Reeves [41:10]: “Help me understand... how that amendment would ensure that a homeowner who decides that they don’t want to sell to black and brown people, they don’t want to sell to LGBTQ folks, how does that amendment help us address the goal of ensuring we don’t exclude people through this private practice?”

Huff [42:06]: “Those are already all addressed in the fair housing federal laws and the Washington laws. We’re all already held to that standard as real estate professionals.”

Representative Ryu then shared personal experience: rejected as a buyer after a seller required in-person offer delivery. ‘Obviously they saw who we were, so we were rejected.’ Existing law did not prevent that experience — which is precisely the enforcement gap the bill addresses and the opt-out would preserve.

The Moral Reframe: Privacy to Segregation

Compass entered both hearings fighting on ‘privacy’ and ‘homeowner autonomy.’ The House committee refused that frame. Representative Reeves recast the practice in terms the opposition cannot survive:

“This does very much feel like unwritten covenants or a form of redlining in this new era.” — Rep. Kristine Reeves [34:52]

Once a committee member connects exclusive listings to redlining, the ‘homeowner choice’ argument becomes a liability. Compass cannot argue that homeowners should have the right to choose segregation-enabling marketing strategies. The privacy frame died in that sentence. Every subsequent reference to ‘autonomy’ now carries the redlining asterisk — and Huff had no prepared response.

Four questions exposed four failures. Huff could not dispute her coalition isolation, could not cite the statutes she claimed were sufficient, could not escape the redlining frame the committee imposed, and never delivered the written business-model explanation she promised the Senate. The script optimized for deflection had no answers for committees that demanded mechanisms — or for commitments that required follow-through.

Cross-Chamber Deterioration: Senate to House

Huff’s House performance was markedly worse than her Senate testimony five days earlier.

The Senate exposed that Huff couldn't go off-script. The House exposed that the script itself was empty. The persistent substitution of a Managing Director for a present Regional VP across both the Senate and House sessions confirms a deliberate “Ghost Panel” strategy. By keeping senior leadership off the record while they personally supervised the proceedings, Compass effectively attempted to bypass the transparency the legislature was seeking to codify.

IV. Why the Compass Script Couldn’t Adapt

The credibility failures documented above raise an obvious question: why didn’t Compass adjust its testimony between chambers? The Senate hearing exposed the business-model vulnerability; the House hearing was five days later. A witness optimizing for influence would have prepared responses for predictable fair housing questions. Huff did not. The rigidity reveals testimony designed for volume documentation — demonstrating ‘opposition on record’ — rather than persuasion calibrated to committee concerns.

The credibility gap is exacerbated by the presence of Regional VP Cris Nelson, who monitored both the Senate and House proceedings in person while remaining silent. Even after witnessing the committee’s hostile reception to Huff’s testimony on Jan 23, Nelson chose to delegate again on Jan 28. This doubling down on a compromised witness suggests a calculated corporate priority: protecting the executive record from discovery risks in federal antitrust litigation, even at the cost of legislative credibility.

After Representative Reeves’s coalition question, Huff could have distinguished Compass’s position from the association’s on substantive grounds. She confirmed the isolation instead. After Representative Santos requested statutory citations, Huff could have provided them or acknowledged the gap. She deflected to the AG instead. The script was load-bearing for the opt-out amendment request; deviation risked inconsistency that could be cited against Compass in future proceedings — including its pending federal litigation against NWMLS and Zillow.

Brandi Huff — House hearing [38:39] “We’re seeking an amendment to sections one and four, adding the simple language ‘or if the homeowner requests otherwise in writing.’ This simple change would ensure that the homeowner, not the state, decides the marketing strategy for their home.”

The twelve-word amendment — ‘or if the homeowner requests otherwise in writing’ — appeared verbatim in both chambers, in VoterVoice campaign materials, and on compass-homeowners.com. Convergence across four independent channels indicates centralized message development. The consistency serves legal positioning: Compass can demonstrate it sought a specific, documented remedy. But consistency that survives different committee questions without adaptation signals that testimony functioned as documentation, not deliberation.

Script rigidity under varied questioning conditions indicates testimony optimized for the record rather than the room. Compass needed documented opposition to the unamended bill; persuading the committee on fair housing enforcement was neither achievable nor, apparently, attempted.

V. Windermere’s Structural Testimony

Compass’s script failures matter less than the structural testimony it could not rebut. The single most damaging argument against Compass came from the firm with the most to gain from private listings. Windermere controls 25% of Washington’s market and 35% of the luxury segment — precisely the inventory private listing networks would capture. If exclusive marketing served seller interests, Windermere would benefit more than any competitor. Instead, Windermere’s leadership testified for transparency in both chambers.

Balance-sheet divergence explains the strategic difference. Windermere operates with patient capital and no debt-service pressure; it can afford to prioritize market health over information control. Compass carries $2.2 billion in accumulated losses and inherited $2.5 billion in debt from the Anywhere merger closed January 10. Quarterly debt service requires margin improvement. Dual-end transactions — capturing both buyer and seller commissions on the same property — deliver that margin. Private listings increase dual-end probability by constraining buyer access to Compass-affiliated agents.

The causal chain is direct: debt pressure → margin requirements → dual-end capture → exclusive listing networks. Compass needs private listings not because they serve sellers better — Windermere’s testimony refutes that claim from the firm best positioned to know. Compass needs them because dual-end capture is the margin mechanism a $4.7 billion debt-and-loss position requires. The opt-out amendment is not a consumer-protection measure; it is balance-sheet relief dressed in homeowner-autonomy language.

Lucy Wood [49:45] — House hearing, Windermere Regional Director “If we were solely driven by profit margins, Windermere would be one of the largest beneficiaries of having a private exclusive listing network. With our market share, we could keep both sides of the transaction in-house and easily recruit brokers to keep growing that market share to the detriment of other brokerages and the consumers... Selfishly, while that would be good for us, that is bad for the consumers.”

Compass never responded to Windermere’s testimony in either chamber. Silence was the only viable response; engaging would have required explaining why Compass needs what Windermere declines. The structural point — that the firm best positioned to exploit private listings supports prohibition — eliminates the argument that transparency harms market competition.

Windermere’s testimony reframes the policy question. The issue is not whether private listings serve consumers — the dominant regional firm answered that by supporting prohibition despite having the most to gain from exclusivity. The question is whether Washington will permit a debt-burdened platform to externalize balance-sheet pressure onto market structure through a signature line in a listing agreement. The opt-out is not about homeowner choice; it is about Compass’s quarterly debt service.

For balance-sheet analysis: Windermere and Compass, Two Philosophies of Real Estate.

VI. The Coalition Problem

Windermere’s testimony was decisive, but the coalition breadth extended far beyond one competitor. Compass’s corporate positioning before the hearings framed the bill as a ‘veiled attempt by NWMLS and Zillow to preserve their market dominance.’ That framing collapsed on contact with the witness list. The PRO coalition included Washington Realtors, Windermere, the Fair Housing Center of Washington, Habitat for Humanity, the Association of Washington Business, and independent brokers warning that private listing networks would drive consolidation eliminating their firms.

Compass Spokesperson — Inman News, January 12, 2026 “This bill is a veiled attempt by NWMLS and Zillow to preserve their market dominance by restricting homeowner choice and limiting competition, to the detriment of sellers and agents alike.”

Huff did not repeat this accusation in either hearing — and for good reason. The ‘veiled attempt’ frame would have been immediately contradicted by Windermere, which holds more market share than Compass, testifying for the bill. The corporate statement assumed a narrow industry dispute; the hearing revealed ecosystem-wide alignment against Compass’s position.

Nicole Bascom-Green — House hearing [01:01:29], independent broker “There is a large brokerage, Compass... who is pushing this pocket listing narrative across the country because they want to be and are essentially the biggest brokerage in the country with a new purchase of Anywhere Real Estate brokerage... Having pocket listings in a market allows a real estate brokerage to control all the flow of information for specific spaces.”

Independent broker Tracy Choate stated the consolidation concern directly: ‘Private exclusive listing networks are poised to drive brokerage consolidation. The result of this being small brokerages, such as mine, will cease to exist.’ The Fair Housing Center warned that pocket listings ‘create conditions where bias, whether intentional or not, can thrive.’ These assessments converged independently — not as Zillow talking points, but as structural observations from across the housing ecosystem.

Coalition breadth signals policy legitimacy. When the sole institutional opponent is the firm whose business model depends on the practice being prohibited — and that firm’s own members’ association supports the bill — the committee can reasonably infer that opposition reflects firm-specific interest rather than market-wide concern.

VII. Committee Disposition

Committee questioning revealed consistent alignment with the bill’s transparency framework. Representative Peterson’s sponsor introduction framed the legislation as preventing entrenchment before platform scale makes prohibition costly — addressing the problem while regulatory intervention remains feasible rather than after a dominant platform has locked in market position.

Representative Peterson — Sponsor introduction [08:05] “Most of us in this room might not think, well, I’m probably not buying that $5 million home anytime soon... But I think it creating a foothold in the state could lead to more of that kind of exclusive, exclusionary practice.”

Representative Reeves’s redlining comparison — documented in Section III — provided the moral frame that no CON testimony addressed. The civil rights framing overwhelmed the data-privacy framing Compass attempted, and Compass had no response prepared. Committee members asked enforcement questions; Compass provided disclosure answers. The mismatch was structural, not rhetorical.

The Attorney General’s office testified ‘other’ — supporting the policy goal while requesting a different enforcement vehicle than the Washington Law Against Discrimination. The technical concern does not challenge the prohibition; it addresses implementation mechanics. The Senate passed SB 6091 with two amendments that did not include the opt-out provision.

Committee signals favor passage. The sponsor framed prevention of entrenchment; the chair expressed support; the members reframed ‘privacy’ as ‘redlining.’ No testimony rebutted the fair housing concerns or Windermere’s structural point. The hearing record supports the same outcome the Senate reached: transparency without exception.

VIII. What the Opt-Out Would Enable

Committee disposition and hearing record point toward passage as written. But the February 3 executive session still presents amendment risk. Understanding what the opt-out would enable — not just what it says — explains why the exception pathway should remain closed.

The twelve-word amendment appears modest: ‘or if the homeowner requests otherwise in writing.’ Statutory exceptions, however, scale with the platforms that use them. At Compass’s current scale — post-merger, the largest brokerage in America with 37,000+ agents — an opt-out provision becomes default intake infrastructure, not a narrow safety accommodation.

Compass has already drafted the 3-Phase Marketing Disclosure Form visible on www.compass-homeowners.com. The form awaits only a statutory hook. Once codified, the opt-out embeds in standard listing agreements. Agents receive training to present it as premium service. The signature accumulates without meaningful informed consent — exactly as arbitration clauses, commission disclosures, and other form provisions accumulate in real estate transactions consumers do not read.

Wisconsin’s opt-out model is the specific mechanism Compass cited in both chambers. But Wisconsin has a fragmented brokerage market with no dominant platform. Washington has Compass — simultaneously litigating against NWMLS and Zillow in federal court while lobbying the legislature to carve out exceptions from the policies those lawsuits attack. At platform scale, the ‘narrow safety accommodation’ becomes the default luxury-market pathway.

The opt-out’s danger lies not in its text but in its deployment context. A signature line in a listing agreement at 37,000-agent scale is not consumer choice — it is information-control infrastructure with a consent wrapper. The Senate passed SB 6091 on January 30 with two amendments that did not include the opt-out provision. The House should follow on February 3.

For apparatus documentation: Compass vs. SB 6091, Narrative Pre-Installation and the Infrastructure of Exception Capture

IX. Recommendations

For House Leadership

Deviation from Senate precedent on the opt-out creates institutional exposure: alignment with a single firm’s carve-out request over the state association’s unanimous position, potential fair-housing scrutiny tied to legislative intent, and documented hearing testimony connecting the practice to redlining. The Senate rejected the opt-out with bipartisan support. Divergence requires explanation the hearing record does not supply.

For the House Committee

Pass HB 2512 without an opt-out provision, following the Senate precedent established January 30. The hearing record provides no substantive basis to deviate. Reject opt-out amendments — the enforcement gap Representative Reeves identified cannot be closed with disclosure language. Address the AG’s technical concerns on WLAD enforcement mechanics without creating a substantive exception pathway.

For Floor Management

Anticipate amendment attempts replicating the opt-out language Compass sought in committee. Prepare response to ‘homeowner choice’ framing: the bill preserves seller control over showing conditions, access timing, and buyer qualification; it addresses only who may see that a listing exists. Reference Windermere’s testimony as dispositive on market-competition claims — the firm with most to gain from private listings supports prohibition.

For Brokers

The hearing record documents which firms support transparency and which oppose it. Agents considering affiliation decisions should note that Washington Realtors — their state association — supported the bill while one member firm organized opposition. The 47 agents who signed in CON while labeling themselves ‘Washington Realtor’ voted against their association’s unanimous position. That pattern is now documented in legislative records accessible to regulators, clients, and future employers.

X. Conclusion

The House hearing was not a close call. Compass deployed a scripted witness who could not answer basic questions about coalition legitimacy, legal sufficiency, or fair housing enforcement. The mobilization collapsed by two-thirds from the prior chamber. The ‘veiled attempt’ media framing was abandoned before testimony began. Windermere testified that the firm with most to gain from private listings supports prohibition. Independent brokers testified that the firm seeking the exception would use it to eliminate competition.

The committee saw through the mechanics. Representative Reeves’s isolation question established that Compass opposes its own association. Representative Santos’s citation request exposed the legal bluff. Representative Ryu’s personal experience demonstrated that ‘existing law’ does not prevent the discrimination the bill addresses. Chair Wallen’s opening comment signaled disposition the CON testimony could not overcome.

The Senate passed SB 6091 on January 30 with two amendments that did not include the opt-out. The twelve words Compass sought — the language that would have converted a transparency bill into information-control infrastructure — did not survive. The House faces the same question with the same evidence. The apparatus is documented. The mobilization is quantified. The credibility failures are on record. The exception pathway should be closed.

Analysis based on public legislative records. No allegation of unlawful conduct is made or implied.

Sources

House Consumer Protection & Business Committee Hearing, January 28, 2026 (TVW)

Senate Housing Committee Hearing, January 23, 2026 (TVW)

Legislative sign-in records, both chambers

Inman News, January 12, 2026 (Compass spokesperson statement)

www.inman.com/2026/01/12/washington-to-consider-requiring-all-listings-to-be-marketed-publicly/

Seattle Agent Magazine, January 14, 2026 (Washington Realtors legislation coverage)

www.seattleagentmagazine.com/2026/01/14/washington-realtors-legislation-private-listing-networks/

Seattle Agent Magazine, April 2025 (Windermere correction on NWMLS board composition)

www.seattleagentmagazine.com/2025/04/28/private-listings-compass-nwmls-clear-cooperation-lawsuit/

Falsification Conditions

This analysis requires revision if: Compass does not pursue opt-out amendments at floor stage; affiliation disclosure rates exceed 50% in subsequent proceedings; similar coordinated opposition does not emerge in other states considering transparency legislation.