MCAI Lex Vision: How Compass's State Legislative Testimony Undermined its Federal Antitrust Claims

Narrative Arbitrage, Inventory Control, and the Collapse of Antitrust Coherence

See companion studies: The Geometry of Regulatory Capture at the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division (Jan 2026), Comparative Externality Costs in Antitrust Enforcement, A Nash–Stigler Foresight Study of Federal Enforcement Equilibria (Jan 2026), Federal Inaction Has Elevated State Authority on Consumer Protection, Antitrust, and Market Integrity (Jan 2026), The Collapse of Compass’s Co-Conspirator Theory (Jan 2026), The Collapse of Compass’s Co-Conspirator Theory (Jan 2026), Compass vs. Competition: The Case for SB 6091 / HB 2512 Without an Opt-Out Exception (Feb 2026).

Executive Summary

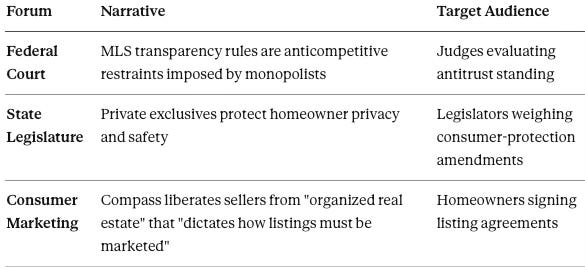

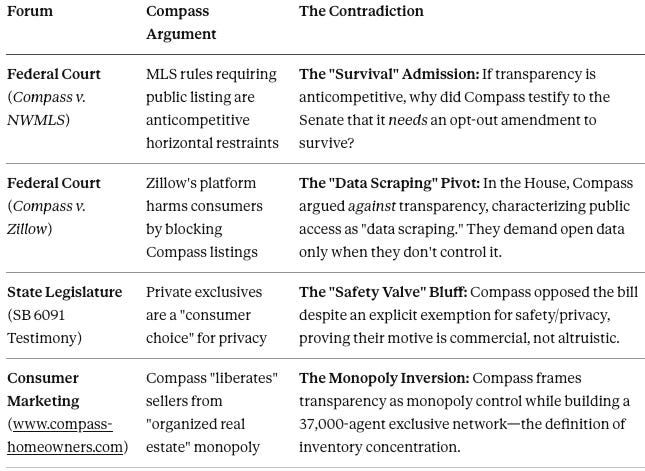

Compass’s antitrust posture collapses under cross-forum scrutiny: when forced to explain its business model outside federal court, the firm advances mutually incompatible theories of competition. The contradiction is not accidental. It is a deliberate strategy of narrative arbitrage: framing the same business practice as pro-competitive innovation, consumer privacy protection, or anti-monopoly rebellion depending on which story serves the immediate objective.

The www.compass-homeowners.com website—launched to support Compass’s legislative and litigation strategy—captures the contradiction in a single quote from CEO Robert Reffkin: “We are building a more open, competitive marketplace—one that gives homeowners and agents real choice, more transparency, and smarter strategies.” The site then explains that Compass’s “3-Phased Marketing Strategy” allows sellers to avoid transparency by keeping listings off public platforms where they would be subject to “negative insights” like days on market and price history.

Transparency is the product when Compass wants data. Transparency is the threat when Compass controls inventory.

The Washington legislative record reveals a single coordinated strategy: use litigation to dismantle open-listing coordination, use “seller choice” rhetoric to normalize private networks, and use scale—financed by subsidized capital—to convert opacity into durable market power.

Every element of the January 2026 hearings—the evasions, the pivots, and the ghost panels—represents that strategy colliding with neutral questioning. Central to this was the persistent, silent presence of Regional VP Cris Nelson, who signed into both the Jan 23 Senate and Jan 28 House hearings but declined to testify. By repeatedly positioning a subordinate as the sole witness, the firm created a strategic buffer between the executive level and the “narrative arbitrage” documented throughout this analysis.

When Compass executives testified before the Washington State Legislature in January 2026, opposing proposed transparency legislation, the testimony did not merely create political controversy; it stress-tested the company’s narrative architecture—and the architecture collapsed. Witnesses could not explain how the business model functions without opt-outs, could not articulate buyer-side effects, could not cite the statutes they claimed already address fair housing concerns, and reduced compliance to “education” rather than enforceable mechanisms.

The present analysis advances a structural claim: the legislative record exposed a contradiction that is not rhetorical but architectural. In court, Compass argues that restricted access to listings is exclusionary and harmful to competition. Before legislators, Compass defended the same restriction as benign seller choice. On its marketing website, Compass frames restricted access as liberation from monopoly control. These three positions cannot coexist. The divergence reveals a market philosophy centered on controlled visibility and internal routing—one that conflicts with the pro-competitive narrative Compass advances in federal court.

MindCast AI’s foresight modeling indicates that large‑scale adoption of private‑exclusive networks increases search friction, fragments inventory, and degrades price discovery—producing multi‑billion‑dollar consumer‑welfare losses over a short horizon when deployed by consolidated actors. The significance of the hearings is therefore evidentiary, not statutory: legislative testimony functioned as inadvertent discovery, surfacing admissions that courts rarely see at the pleading stage. The pattern is not unique to Washington and will recur wherever consolidated market actors are asked to explain their models outside a litigation forum.

MindCast AI is a predictive cognitive intelligence system that models how institutions behave under constraint, using Cognitive Digital Twins to generate publicly falsifiable foresight rather than retrospective explanation or advocacy. In this paper, MindCast AI first assembles an evidentiary record drawn from sworn legislative testimony, public marketing materials, and litigation posture to identify structural contradictions in Compass’s competition narrative. That record is then used as input for a formal Foresight Simulation in Section VIII, which projects likely legislative, market, and litigation outcomes based on observed incentives, constraint geometry, and coordination dynamics—making clear what follows if current structures persist, and what outcomes would falsify the model.

How Other States Should Use This Record

The analysis presented here is not Washington‑specific advocacy. It is a portable legislative and enforcement playbookfor any state confronting coordinated lobbying for exclusive‑listing carve‑outs by a consolidated brokerage.

Legislators elsewhere should treat the Washington record as pre‑answered testimony. The core claims Compass advances in other states—seller choice, privacy, fair‑housing compliance through disclosure, and harm from “data scraping” platforms—were all raised, tested under neutral questioning, and failed on the record. State lawmakers do not need to re‑litigate those claims. They can cite that when pressed under oath, Compass could not explain how its model functions at scale without opt‑outs, could not articulate buyer‑side effects, and reduced fair‑housing compliance to education rather than enforceable mechanisms.

Practically, the record equips legislators to do three things in real time: (1) rebut opt‑out amendments by pointing to the explicit admission that Compass’s business model depends on them; (2) neutralize privacy and safety arguments by noting that the Washington bill already contained a safety exception Compass opposed anyway; and (3) counter incumbent‑protection rhetoric by citing Windermere’s testimony that private exclusives would advantage the largest firm—and harm consumers.

For committees and sponsors, the lesson is structural rather than partisan. Exclusive‑listing proposals follow a repeatable pattern: litigation frames transparency as anticompetitive; lobbying reframes opacity as consumer choice; neutral questioning exposes the inconsistency. The following sections show how to surface that pattern quickly, without relying on ideology or conjecture, and how to anchor legislative debate in an evidentiary record that will withstand post‑enactment scrutiny.

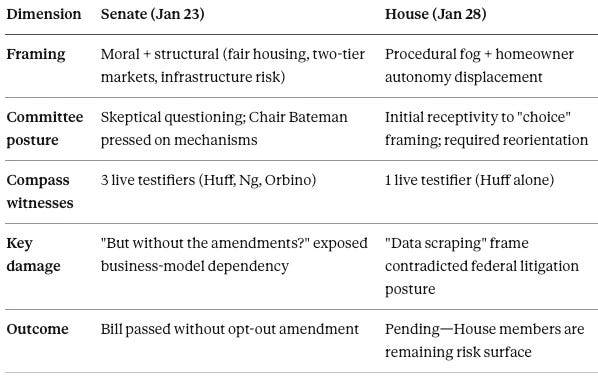

The Senate → House Contrast

The two hearings produced different dynamics. Understanding the shift clarifies where narrative traction weakened and where legislative risk remains.

The Senate hearing broke the narrative. The House hearing showed the apparatus in retreat—unable to field witnesses, unable to sustain coordination, unable to answer the questions the Senate had already surfaced. House members evaluating HB 2512 should recognize that the “seller choice” arguments they will hear have already been stress-tested and failed. Nelson’s continued silence in the House, after witnessing the Senate’s reception to testimony on Jan 23, confirms this was a deliberate shielding strategy rather than a scheduling fluke. Despite the Regional VP’s presence across both chambers, the task of defending the model was delegated to a Managing Director, signaling that corporate insulation took priority over legislative clarity.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. We specialize in complex litigation, antitrust, state-federal regulation, national innovation policy. Recent publication: Runtime Geometry, A Framework for Predictive Institutional Economics (Jan 2026), Competitive Federalism as Market Infrastructure (Jan 2026), The Validation Node, Washington State as Competitive Federalism in Operation (Jan 2026).

I. The Structural Diagnosis: Narrative Arbitrage as Antitrust Signal

Antitrust analysis depends on coherence across forums. A plaintiff may advance aggressive theories, but those theories must describe the same market reality whether addressed to a court, a regulator, a legislature, or consumers. When a firm’s explanation of how competition works changes depending on the audience, the divergence becomes probative. Legislative testimony here functioned as inadvertent discovery: contemporaneous, unscripted explanations of market operation that courts rarely receive at the pleading stage.

Compass’s federal complaints rely on a clear premise: limiting access to listings distorts competition, entrenches market power, and harms consumers. Before legislators, Compass defended the same restriction as benign seller choice, privacy protection, and resistance to “data scraping.” On www.compass-homeowners.com, Compass markets restricted access as freedom from “organized real estate” that “dictates how listings must be marketed.”

The company’s website is particularly revealing. It frames MLS transparency requirements as monopolistic control while simultaneously marketing Compass’s ability to keep listings hidden from those same platforms:

“For decades, organized real estate, including multiple listing services, associations, and online portals, have dictated how homes are marketed and sold in the United States. These entities profit from controlling access to listings and information, limiting both competition and consumer choice.”

Yet the same page explains that Compass Private Exclusives allow sellers to “make your listing available to a nationwide network of 37,000 top agents” while avoiding public platforms—precisely the access restriction Compass claims is anticompetitive when imposed by others.

MindCast AI’s prior analysis of Compass’s narrative pre‑installation strategy identified, in advance of the hearings, how Compass seeded antitrust language (”consumer choice,” “innovation,” “incumbent protection”) into non‑judicial forums. Legislative testimony tested that pre‑installed narrative under neutral questioning—and the narrative failed.

The Three-Forum Contradiction

The hearings exposed a classic Baptist-and-Bootlegger pattern—the regulatory-capture dynamic economist Bruce Yandle identified in which public-interest advocates and private beneficiaries align behind the same policy for different reasons. (This is a textbook Baptist-and-Bootlegger dynamic: moral advocates supply public justification, while concentrated economic actors capture the rents.)

Baptists = Privacy-forward seller narratives, senior vulnerability arguments, fair-housing rhetoric framing transparency as intrusion

Bootleggers = Platform-scale brokers capturing double-ended commissions, data advantage over competitors, and foreclosure of independent rivals

Legislative questioning separated the two—exposing that Compass’s public arguments (privacy, safety, autonomy) masked private reliance on opt-outs that preserve internal routing and inventory control.

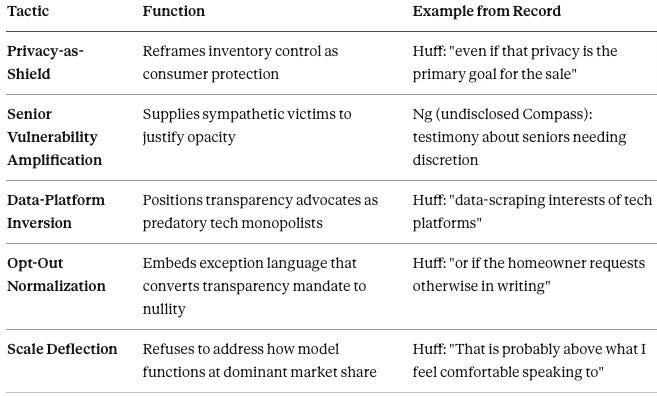

The Tactical Pattern: Testimony as Behavioral Fingerprint

The testimony excerpts throughout this document are not anecdotes—they are instances of repeatable tactics. Recognizing the pattern allows legislators to anticipate arguments before they are made:

These tactics are not Washington-specific. They will reappear in other states because they are load-bearing for Compass’s business model. Legislators who recognize the pattern can short-circuit the narrative before it gains traction.

Legislative testimony revealed an incoherence that weakens Compass’s federal claims by destabilizing its competition narrative across all relevant forums. The same firm cannot credibly argue that transparency rules harm competition while lobbying for exemptions from transparency and marketing opacity as liberation from monopoly.

Insight: Narrative arbitrage works only when forums remain siloed. Once legislative testimony enters the litigation record, the arbitrage collapses—and the contradictions become evidence.

II. Two Market Philosophies, One Antitrust Problem

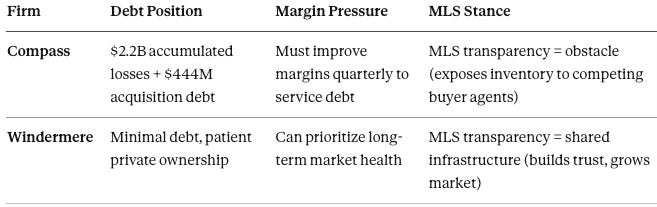

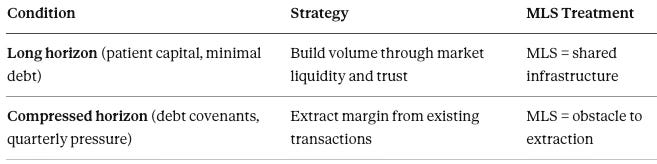

The testimony divergence is best understood not as a misstep, but as the expression of a distinct market philosophy shaped by balance-sheet pressure. Compass and Windermere operate in the same markets, under the same rules, yet articulated opposite views of how competition should function. MindCast AI’s analysis of competing market philosophies in residential real estate explored the structural drivers behind the contrast.

The Balance Sheet Forcing Function

Windermere described the MLS as shared market infrastructure—an information commons that lowers transaction costs, broadens participation, and constrains even the largest firms from hoarding inventory. Windermere can afford that position because the firm carries no debt service pressure forcing quarter-to-quarter margin extraction.

Compass faces a different incentive geometry. The company carries substantial debt from its acquisition strategy—most recently the $444 million purchase of @properties Christie’s International Real Estate, layered onto $2.2 billion in accumulated losses (2019-2024). Debt service creates profit-timeframe compression: the firm must generate returns on a schedule that patient market-building cannot satisfy.

The “Nelson Substitution”—maintained across both legislative sessions—is a byproduct of this debt-driven pressure. By remaining off the record while personally monitoring the hearings, senior leadership attempted to shield the firm from making statements that would expose how their internal routing mechanisms function as a predatory tool for servicing this debt.

The Double-End Mechanism

Private exclusives solve Compass’s balance-sheet problem through a specific mechanism: double-ending transactions—capturing both the seller-side and buyer-side commission on the same sale. The mechanics work as follows:

Standard transaction: Seller hires Listing Agent (3% commission). Buyer hires Buyer’s Agent (3% commission). Two brokerages split the 6% total.

Double-ended transaction: Same agent or brokerage represents both sides. One firm captures the full 6%.

Private exclusives enable double-ending: When a listing is hidden from public platforms and other brokerages, buyers must come through Compass agents to even see the property. Inventory control creates commission capture.

On a $1 million home, the difference between a standard split (3% = $30,000) and a double-end (6% = $60,000) is $30,000 per transaction. At scale—37,000 agents, thousands of transactions—private exclusives become a margin extraction machine.

Why Compass Needs Private Listings and Windermere Doesn’t

The causal chain is direct: debt pressure → margin requirements → double-end capture → private exclusives → legislative opposition to transparency mandates.

Chair Bateman’s question—”But without the amendments?”—was really asking: “Can your business model survive if you can’t double-end transactions?” The answer Compass Managing Director Brandi Huff declined to give is no. Private exclusives are not a consumer feature; they are a survival lever for a firm whose balance sheet demands margin extraction over market stewardship.

The “Data Scraping” Smoking Gun

The narrative arbitrage becomes legally perilous when examined closely. In federal court, Compass sues Zillow for restricting access to listing data, arguing that such restrictions harm consumers and distort competition. Data access, in Compass’s federal pleadings, is essential market infrastructure.

In the House hearing, Brandi Huff explicitly framed public visibility as a vice:

“We must ask who the true beneficiaries are of this bill. It is not the homeowner. It is the dominant third-party platform providers whose business models rely on the harvesting of data of every available listing. The state should not be legislating to protect those data-scraping interests of tech platforms at the expense of homeowners’ rights to decide how their largest asset is marketed.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 38:39–40:46)

Here is the clearest evidence that Compass defines “open markets” solely as “markets Compass controls.” The firm cannot simultaneously:

Ask a federal judge to force Zillow and NWMLS to share data (claiming it is essential market infrastructure), while

Telling state legislators that sharing data is merely “scraping” that violates seller privacy

Defense counsel in both federal cases can now argue: “Compass’s own legislative testimony proves that ‘data access’ is not a consumer-protection principle for this plaintiff—it is a competitive weapon deployed selectively depending on who controls the data.”

The Legislative Evidence

The legislative testimony revealed the balance-sheet structure directly. When Brandi Huff, Compass’s Managing Director for the Pacific Northwest and a 15-year real estate professional, was asked by Senator Alvarado how Compass’s position as “the largest Wall Street-backed real estate brokerage in the country” interacts with exclusive networks, Huff could only confirm the model works “specifically with the amendments.” When Chair Bateman pressed—”But without the amendments?”—Huff declined to answer: “That is probably above what I feel comfortable speaking to.” (Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 44:41–45:37)

The evasion confirms the dependency—Compass cannot explain how its model functions at scale without the very restrictions it claims are anticompetitive when imposed by others. The full exchange is analyzed in Section IV.

Before the House committee, Huff reframed transparency as serving “dominant third‑party platform providers whose business models rely on harvesting data,” arguing that the state should not protect “data‑scraping interests of tech platforms” (House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 38:39–40:46). The reframe is telling: Compass attacks Zillow for restricting access in federal court while defending its own access restrictions before legislators as protection against “data scraping.”

The Windermere Contrast

The contrast with Windermere is dispositive not because of what Windermere’s executives said, but because of what Windermere’s financial position allows:

OB Jacobi, President of Windermere Real Estate, testified before the Senate: “Windermere is the largest brokerage in Washington State by a lot. We have 4,000 agents... and 154 offices across the state. We enjoy a 25% market share across all price points and a 35% in the luxury space... We would clean house, if you would, if this bill doesn’t pass, which sounds ridiculous. We’ve worked really, really hard for decades to create a fair and open marketplace that’s transparent.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 50:38)

Lucy Wood, Windermere’s Western Washington Regional Director, reinforced the point before the House:

“With our market share, we could keep both sides of the transaction in-house and easily recruit brokers to keep growing that market share to the detriment of other brokerages and the consumers... And selfishly, while that would be good for us, that is bad for the consumers because it restricts access to the information that both buyers and sellers need to make smart fiscal decisions.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 49:45)

A firm without debt pressure can prioritize long-term market health over short-term margin capture. Compass cannot. If transparency rules entrenched incumbents—as Compass argues in federal court—the dominant incumbent would oppose them. Windermere’s support for transparency falsifies Compass’s “incumbent protection” theory.

The Windermere–Compass contrast falsifies the claim that transparency is anticompetitive. Compass’s litigation posture reflects an extractive market philosophy driven by debt-service pressure, not market necessity or consumer benefit.

Insight: Balance sheets explain behavior that rhetoric obscures. Follow the debt service, and the legislative strategy becomes predictable.

III. The Safety Valve Bluff

Compass’s privacy and safety arguments collapse upon examination of the statutory text. The Senate hearing began by clarifying a critical point that undercuts Compass’s irreparable‑harm and coercion theories: SB 6091 already contains an explicit safety exception.

John Kim (Committee Staff): “The bill before you prohibits a real estate broker except as reasonably necessary to protect the health or safety of the owner or occupant from marketing the sale or lease of residential real estate to a limited or exclusive group of prospective buyers or brokers unless the real estate is concurrently marketed to the general public and all other brokers.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 00:26)

Senate Bill sponsor Jesse Elias stated plainly that the bill does not compel public access or physical intrusion:

Senator Elias: “If somebody wants to sell their property privately... we don’t have to list it. We can do a private party sale. But when I decide to list it for sale, that listing should be available to everybody... You don’t have to allow open houses. You don’t have to allow everyone into your home. Everybody must know the home is for sale and be able to make an offer.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 03:27–06:53)

Senator Elias’s explanation collapses the claim that transparency mandates force unwanted exposure. Compass opposed the bill anyway—revealing that the objection was never about privacy or safety, but about preserving the opt‑out architecture on which its business model depends.

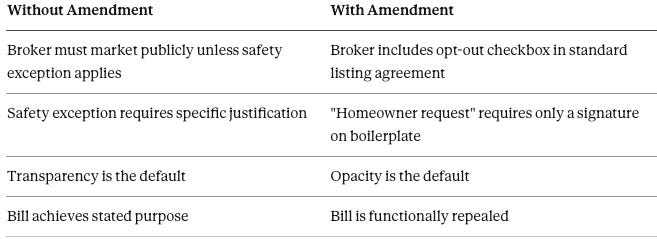

The Poison Pill: Repeal Disguised as Amendment

Compass’s requested amendment—adding “or if the homeowner requests otherwise in writing”—is not a narrow safety accommodation. It is a self-canceling provision that would render the statute a nullity.

Standard listing agreements are form contracts. If the amendment passes, brokerages would simply add a pre-checked “opt-out” clause to their standard forms. Sellers signing listing agreements—already dozens of pages of boilerplate—would “request otherwise in writing” without meaningful deliberation. The opt-out would become the default, not the exception.

The legislative mechanics are straightforward:

Legislators should recognize the amendment as a poison pill: it allows Compass to claim support for the concept of transparency while inserting ten words that legally delete the bill’s function. The amendment doesn’t modify the bill—it reverses it.

The Opt-Out Failure Mode

At platform scale, opt-out regimes fail by design. They are embedded at contract intake, framed as premium service, and routinized through agent training—converting nominal choice into systematic exclusion.

Compass has already drafted the disclosure form visible on www.compass-homeowners.com. The infrastructure awaits only a statutory hook. Once codified, the opt-out embeds in standard listing agreements across 37,000+ agents. The signature accumulates without meaningful informed consent—exactly as arbitration clauses, commission disclosures, and other form provisions accumulate in real estate transactions consumers do not read.

By opposing a bill that already protects safety, Compass admitted that “safety” is a pretext. The requested amendment confirms the intent: not narrow accommodation, but wholesale nullification.

Insight: When a firm opposes a bill that already contains the exception it claims to need, the stated rationale is not the actual rationale.

IV. Scale Blindness and Buyer‑Side Evasion

Antitrust law turns on scale. Conduct that appears benign at small size can become exclusionary when deployed by a large or rapidly consolidating actor. Compass relies on exactly that principle in federal court when challenging Zillow and NWMLS—yet when legislators pressed Compass to explain how its model behaves at scale, witnesses declined to engage.

Senator Emily Alvarado, Vice Chair of the Housing Committee, questioned Huff directly: “You said you were with Compass... My understanding is that recently the Trump administration approved a merger that makes Compass now the largest Wall Street-backed real estate brokerage in the country. And then when you layer on an exclusive network, I’m wondering what that means for broader competitiveness of housing selling and buying in our state.”

Huff: “I feel fully confident to say that the Compass business model would not be affected by this bill, specifically with the amendments for the sellers to have the right to make their own choice.”

Chair Jessica Bateman pressed further: “But without the amendments?”

Huff: “That is probably above what I feel comfortable speaking to...”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 44:41–45:37)

The refusal to address scale effects is not incidental; it is a silence bearing directly on market‑definition and competitive‑effects analysis. Huff’s answer confirmed that Compass’s business model depends on opt‑out amendments—an admission that undercuts the company’s federal claims that such rules are merely anticompetitive restraints rather than necessary consumer protections.

The Buyer-Side Silence

When asked whether buyers outside Compass networks are disadvantaged during private phases, Compass redirected to seller preference and avoided buyer‑side analysis altogether. Throughout the House hearing, responses returned to seller preference without addressing buyer impact or price discovery.

The silence contrasts sharply with practitioner testimony. Sol Villarreal, an independent Seattle Realtor with over a decade of experience, told the Senate:

“Right now, when I have a listing, five minutes after I press publish, it’s available on every public-facing search portal to anyone who’s looking for real estate in Seattle. It doesn’t matter which company their real estate agent works for or even whether they have an agent. That’s important for sellers because it maximizes their potential audience and helps them get the best price for their house... In my 11 years of helping clients buy and sell homes, I’ve never had a seller who asked me if it was possible to restrict the number of people who could see their home. Sellers want to get their homes in front of as many potential buyers as possible, so this isn’t something that’s organically coming from sellers.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 01:06:44)

The divergence suggests that the asserted “seller choice” rationale is manufactured by brokerage incentives rather than driven by market demand.

The Coasean Framework

From a Coasean perspective, the evasion matters because private‑exclusive networks raise transaction costs and create information asymmetry. As established in MindCast AI’s Chicago School Accelerated framework, the distinction between transaction costs and coordination costs is analytically critical: private‑exclusive networks fragment inventory visibility, increase buyer search friction, and degrade price discovery—producing the multi‑billion‑dollar consumer‑welfare losses that Coasean analysis predicts when inventory sequestration is deployed by consolidated actors.

The Price Suppression Mechanism

Private exclusives harm sellers, not just buyers. MindCast AI’s analysis of SB 6091 identifies the core economic distortion: private exclusives mislead sellers into believing that “curated exposure” increases value, when in reality it narrows buyer pools and compresses competitive discovery.

The mechanism operates through three channels:

Compression of competitive discovery: By limiting the audience to a specific network, the property does not receive the broad market exposure necessary to reach a true market-clearing price. Sellers accept offers from a constrained pool rather than testing the full demand curve.

Exploitation of scarcity bias: The “exclusive” positioning substitutes true market demand with a constrained buyer pool. Brokerages exploit scarcity bias—making properties appear valuable through artificial limits rather than through competitive bidding from the open market.

Information asymmetry as monetization: The goal is to convert network size into information asymmetry. By withholding inventory from public portals and rival brokerages, consolidated firms create a two-tiered system where insiders get early access—effectively restraining the demand curve to their own agents at the expense of the seller’s potential to receive higher offers from outside the network.

The irony is precise: Compass markets private exclusives as a premium service that maximizes seller value, while the economic structure systematically depresses sale prices by eliminating the competitive bidding that open markets produce. Sellers pay for the privilege of receiving lower offers.

Evasion on scale and buyer effects undermines core antitrust elements while signaling broader consumer‑welfare risks associated with inventory sequestration.

Insight: Silence under questioning is often more probative than testimony. What a witness declines to explain reveals the model’s vulnerabilities.

V. Fair Housing as Consequence, Not Justification

The legislative record did not turn on allegations of discriminatory intent. Legislators focused instead on structural access: who sees listings, when, and under what conditions. Such framing aligns with modern antitrust and civil‑rights enforcement, which increasingly recognizes that discriminatory outcomes can flow from facially neutral practices.

Senator Chris Gaynor, Ranking Member of the Housing Committee, pressed Huff on enforcement:

“If I understood you correctly, you were saying that you would like to see an amendment that would allow the seller to opt out of public marketing. But then you also said that and still meet the fair housing requirements. So how would that happen? Because it does seem like if you are opting out of exposure that you may be running afoul of that. So how would you ensure that those fair housing laws would be enforced or adhered to?“

Huff: “Currently, as a real estate professional, we are obligated to provide the disclosures to the seller regarding fair housing and make sure that they understand and comply with them to the best of our ability... The disclosure would give them the opportunity to not only opt out of public marketing, but to understand fully fair housing.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 45:59–46:33)

Chair Bateman pressed further on how compliance would actually be ensured when marketing is limited to a select group. No concrete enforcement mechanism was offered beyond education and disclosure:

Chair Bateman: “So how would you ensure that the Fair Housing Act is actually abided by when you’re just marketing it to a select group of people and not opening it up to the public?”

Huff: “I think our job as a professional is to educate the client on fair housing and make sure that they continue to comply with that to the best of our ability. That’s not an always and every day. And I’ll acknowledge that that is still sometimes a problem.“

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 47:21–47:31)

The admission is significant: Compass conceded that its model creates fair‑housing risk while offering no mechanism to address it beyond seller education. Discrimination risk flows from structure, not intent—and disclosure alone cannot police exclusion occurring before public exposure.

Fair‑housing concerns emerge as downstream consequences of access control, reinforcing—rather than substituting for—the competition analysis and highlighting enforcement risk.

Insight: “Education” is not enforcement. When a witness reduces compliance to disclosure, the gap between stated mechanism and actual protection becomes the legislative question.

VI. The Exclusionary Consensus

The evidentiary force of the January 2026 hearings lies not in Compass’s admissions alone, but in the breadth of opposition. The legislative record reveals that resistance to private exclusives spans the entire market ecosystem—from housing advocates to independent brokers to the market leader—who all identified the practice as exclusionary.

The Consumer Advocates: Who Gets Harmed

Adria Buchanan, Executive Director of the Fair Housing Center of Washington, provided the clearest articulation of consumer harm:

“Pocket listings... reduce access, they limit competition, and they shut out people well before they even have a chance to participate. A company might use pocket listings to double-end commissions... to ensure higher agent retention by leveraging their growing exclusive network... to control transaction flow, limiting days on market, and to gather private data on buyers and pricing trends that they could potentially monetize later. None of these benefits help consumers or the legislature’s goals of increasing housing access and supply.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 01:03:59)

Ryan Donahue, Chief Advocacy Officer of Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King County, framed the issue as structural exclusion:

“When homes are marketed privately through private listings, access is no longer based on openness and merit, but instead proximity to the right networks—who you know, not for having the opportunity to actually have access to purchasing homes... A study out of Chicago found that hidden listings may be reinforcing racial divides, highlighting how off-market practices can deepen segregation and inequality.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 40:03)

The Independent Brokers: The Actual Antitrust Victims

The consumer advocates described systemic harm. The independent brokers described how that harm translates to market foreclosure—the classic antitrust injury.

Nicole Baskin-Green, owner of a six-person independent brokerage in Seattle, testified:

“So imagine the largest brokerage in the country is having pocket listings in marketplaces where ultimately the bottom line is they can control both sides of the transaction... And then locking folks out, like myself, out of this marketplace. Having pocket listings in a market allows a real estate brokerage to control all the flow of information for specific spaces... Buyers cannot get access to that information. A small real estate brokerage like myself of six, we can’t get access to that information. And we can’t support our community the way that we would like to.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 01:01:29)

Tracy Choate, owner of a 40-person brokerage in Lacey and past president of Thurston County Realtors, connected exclusion to market consolidation:

“I believe private exclusive listing networks are poised to drive brokerage consolidation. The result of this being small brokerages, such as mine, will cease to exist, and consumers may end up with one or two monolithic firms controlling who and how people can buy or sell their real estate.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 51:49)

Sol Villarreal, an independent Seattle Realtor with over a decade of experience, confirmed that private listings are not seller-driven—they are brokerage-driven:

“In my 11 years of helping clients buy and sell homes, I’ve never had a seller who asked me if it was possible to restrict the number of people who could see their home. Sellers want to get their homes in front of as many potential buyers as possible, so this isn’t something that’s organically coming from sellers.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 01:06:44)

The Market Leader’s Threat Assessment

Windermere’s testimony is significant not as moral leadership but as technical confirmation that private exclusives are an exclusionary weapon. The state’s dominant firm admitted that if it deployed private listing networks, it would destroy competition.

OB Jacobi, President of Windermere Real Estate, testified:

“Windermere is the largest brokerage in Washington State by a lot. We have 4,000 agents... We enjoy a 25% market share across all price points and a 35% in the luxury space. And to put it in perspective, the nearest competitor is 8%... And to say that no other company would reap the benefits of a private listing network would be Windermere. We would clean house, if you would, if this bill doesn’t pass, which sounds ridiculous.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 50:38)

Lucy Wood, Windermere’s Western Washington Regional Director, was more explicit about the mechanism:

“If we were solely driven by profit margins, Windermere would be one of the largest beneficiaries of having a private exclusive listing network. With our market share, we could keep both sides of the transaction in-house and easily recruit brokers to keep growing that market share to the detriment of other brokerages and the consumers... And selfishly, while that would be good for us, that is bad for the consumers.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 49:45)

The Windermere testimony is not corporate heroism. It is a threat assessment from the firm best positioned to know. Windermere is saying: this tool is a monopolization engine; we choose not to use it; Compass is fighting for the right to deploy it against us and everyone else.

Compass isn’t fighting a monopoly. Compass is fighting for the right to build one—using the exact tool the current market leader says is too dangerous to deploy.

The Trade Association’s Unanimous Opposition

James Fisher, Vice President of Government Affairs for Washington Realtors, confirmed that opposition to Compass is industry-wide:

“Washington Realtors remains committed to progress, so our Legislative Issues Committee voted unanimously in collaboration with our leadership team to support this bill. Since that time, we’ve heard from a number of our members, brokerages, industry partners across the state, except from one firm.We are proud to support SB 6091.”

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 38:28)

Coordinated Non-Disclosure: The Senate Pattern

Against this unified opposition, Compass mounted coordinated resistance while concealing affiliation. More than 160 individuals signed in opposition at the Senate hearing while disclosing affiliation with Compass at a rate of roughly one in seventeen. At least one testifier presented herself as a neutral senior-advocacy professional while omitting her Compass management role:

Jennifer Ng testified as “a nationally certified senior advisor... a licensed real estate broker, a member of the Washington State Association of Realtors, and a certified licensed instructor” about protecting vulnerable seniors needing to sell homes privately.

She did not disclose she is Sales Manager at Compass Fremont. Her Compass bio lists every credential she cited in testimony—except Compass itself.

(Senate Housing Committee, Jan. 23, 2026, 56:04)

The House Collapse: Ghost Panels and Mobilization Fatigue

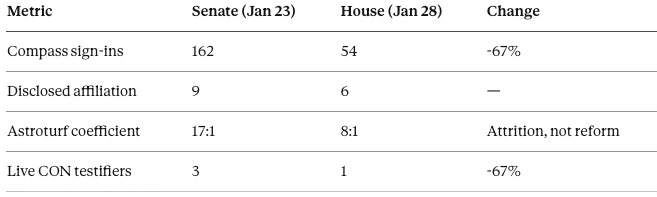

The House hearing revealed that Compass’s coordinated opposition could not sustain itself under continued scrutiny. Participation dropped 67% between chambers—from 162 sign-ins at the Senate to 54 at the House—while concealment rates remained constant.

More revealing was the Ghost Panel: ten individuals signed up to testify CON—explicitly requesting speaking time—then failed to appear when called. All ten are verified Compass brokers. Nine concealed their affiliation on sign-in sheets.

The Ghost Panel was not random attrition; it involved key narrative surrogates. Michael Orbino—who delivered the emotional “elderly sellers and divorcees” testimony in the Senate, framing private exclusives as protection for vulnerable populations—signed in for the House hearing and was explicitly invited to the Zoom room by Chair Wallen:

Chair Wallen: “Before I call on Ryan, I’m going to invite into the Zoom room Ming Zhao, Michael Orbino, and Sean Haley.”

(House Consumer Protection & Business Committee, Jan. 28, 2026, 58:01)

Orbino never spoke. The transcript shows the Chair moved immediately to other testifiers. His disappearance suggests tactical retreat. His Senate testimony had provided the “Baptist” moral cover (protecting the vulnerable) for Compass’s “Bootlegger” commercial interest (preserving double-end capture). Once the “privacy” narrative began collapsing under questioning in the Senate—with Chair Bateman’s “But without the amendments?” exposing the business-model dependency—Compass withdrew its storytellers rather than exposing them to a House committee that had already signaled hostility to the framing.

The Ghost Panel achieved its tactical objective: inflating opposition count on the official record without exposing additional witnesses to the scrutiny that damaged Huff. But the tactic is now visible. Ten Compass brokers signed up to testify, concealed their affiliation, and went silent when called. The apparatus could fill sign-in sheets but could not fill witness chairs.

The coalition opposing private exclusives—consumer advocates, fair housing organizations, independent brokers, and the market leader—identified the same harm from different vantage points: exclusion, foreclosure, consolidation, discrimination risk. The isolation of Compass as the sole institutional opponent confirms that its position reflects firm-specific financial imperatives, not market consensus or consumer benefit.

Insight: When an entire industry ecosystem aligns against a single firm’s position, the burden shifts. The question is no longer “why regulate?” but “why carve out an exception for the one firm asking?”

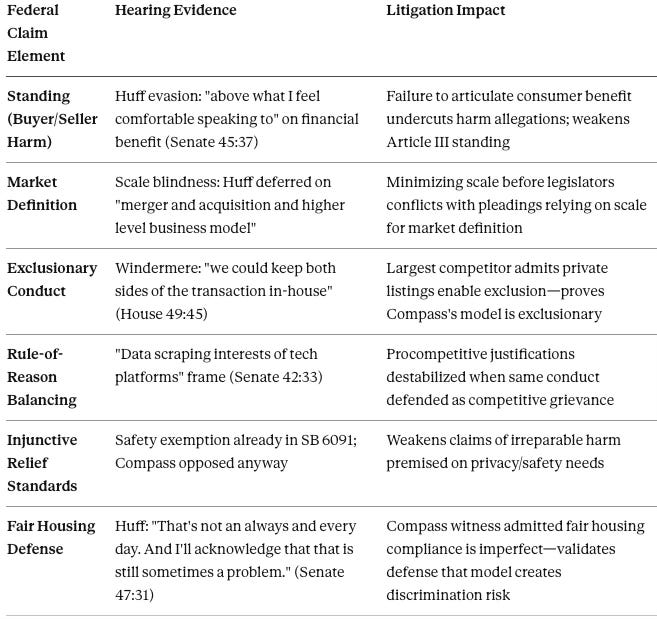

VII. Legal Implications for Federal Antitrust Claims

The legislative record reshapes litigation risk across multiple dimensions. Defense counsel and enforcement authorities now have a documented evidentiary trail connecting Compass’s public arguments to operational admissions.

Antitrust Vulnerabilities Matrix

The Standing Problem

Compass’s federal claims against Zillow and NWMLS rest on allegations that restricted data access harms consumers and distorts competition. Article III standing requires plaintiffs to demonstrate concrete injury traceable to defendant conduct. When Huff declined to explain how Compass’s business model benefits consumers without opt-out amendments—”That is probably above what I feel comfortable speaking to”—she created a gap that defense counsel can exploit.

The argument writes itself: if Compass’s own Managing Director cannot articulate how private exclusives benefit consumers when asked directly by legislators, the company cannot credibly claim that defendants’ conduct causes consumer harm. Standing doctrine requires injury to legally protected interests. A witness who evades questions about consumer benefit under neutral questioning undermines the factual predicate for harm allegations.

The Market Definition Contradiction

Antitrust plaintiffs must define relevant markets to establish competitive effects. Compass’s federal pleadings emphasize the company’s national scale and the concentrated structure of the brokerage industry—arguments that depend on treating Compass as a significant market participant whose exclusion causes measurable harm.

Before the Washington Legislature, Huff minimized scale considerations entirely, deferring questions about “merger and acquisition and higher level business model” as beyond her competence. Defense counsel can juxtapose these positions: Compass cannot simultaneously claim its exclusion from data access constitutes market-wide harm (requiring significant market presence) while telling legislators that scale effects are above its witness’s pay grade. The inconsistency goes to the coherence of the antitrust theory itself.

The Exclusionary Conduct Admission

Windermere’s testimony provides Compass’s opponents with a devastating admission from an unimpeachable source. When the state’s largest brokerage—holding 25% market share, three times its nearest competitor—testifies that private listing networks would allow it to “clean house” and “keep both sides of the transaction in-house to the detriment of other brokerages and consumers,” that testimony constitutes expert economic analysis from the firm best positioned to know.

Defense counsel in both federal cases can cite Windermere’s testimony as market-participant confirmation that private exclusives are inherently exclusionary. The argument: Compass’s own business model—defended before the legislature—is the same model that the dominant incumbent describes as a monopolization tool. Compass cannot claim its conduct is procompetitive when the market leader explains precisely how the same conduct would destroy competition if deployed at scale.

The Rule-of-Reason Collapse

Under rule-of-reason analysis, courts weigh procompetitive justifications against anticompetitive effects. Compass’s federal claims depend on characterizing MLS transparency rules as naked restraints lacking procompetitive justification. The “data scraping” testimony inverts this framework catastrophically.

By framing public data access as predatory “scraping” before the House committee, Compass Managing Director Brandi Huff supplied defendants with a ready-made procompetitive justification for the very rules Compass challenges. If transparency enables “data scraping” that harms consumers—as Compass told legislators—then rules requiring transparency serve procompetitive purposes that courts must weigh under rule-of-reason analysis. Compass created the defense’s best argument: the plaintiff itself testified that unrestricted data access causes the harms that MLS rules prevent.

The Irreparable Harm Deficit

Preliminary injunction standards require plaintiffs to demonstrate irreparable harm absent relief. Compass’s federal claims invoke privacy and safety concerns as grounds for injunctive relief against transparency mandates. The Washington record eviscerates this theory.

SB 6091 already contained an explicit safety exception—”except as reasonably necessary to protect the health or safety of the owner or occupant.” Compass opposed the bill anyway. Defense counsel can argue that Compass’s own legislative conduct proves that privacy and safety are pretextual: a plaintiff genuinely concerned with irreparable privacy harm would support legislation containing privacy protections, not oppose it while demanding amendments that would nullify the entire statute.

The Fair Housing Exposure

Compass’s admission that fair housing compliance is “not an always and every day” and “still sometimes a problem” creates litigation risk beyond the pending federal cases. Fair housing plaintiffs, enforcement agencies, and intervenors now have a contemporaneous admission from a Compass executive that the company’s model creates discrimination risk without adequate safeguards.

More immediately, defendants in the federal cases can invoke fair housing concerns as an independent justification for transparency rules. If private exclusives create discrimination risk—as Compass conceded—then rules requiring public listing serve civil rights objectives that courts must consider when balancing competitive effects. Compass handed its opponents a policy justification rooted in the company’s own assessment of its compliance gaps.

State‑Action Immunity

Where a legislature clearly articulates and actively supervises a transparency requirement, private actors implementing that policy are shielded from federal antitrust liability under Parker v. Brown, 317 U.S. 341 (1943). The hearings themselves—by clarifying purpose, scope, and enforcement—strengthen that immunity and narrow Compass’s remedial path.

Courts routinely consider sworn testimony, public statements, and contemporaneous legislative records when assessing credibility and Rule‑of‑Reason balancing. Legislative testimony occupies a similar evidentiary space, particularly when it concerns operational realities.

The January 2026 hearings introduced coherence, credibility, coordination, and immunity risks that defense counsel and enforcement authorities can exploit in both federal cases. Each vulnerability compounds the others: standing problems undermine market definition arguments; market definition contradictions destabilize rule-of-reason balancing; rule-of-reason collapse eliminates procompetitive justifications for injunctive relief. The cumulative effect is a litigation posture that legislative testimony has systematically weakened across every element required to prevail.

Insight: Legislative testimony is discoverable and citable. Statements made to secure a carve-out can become admissions in a motion to dismiss.

VIII. Foresight Simulation Predictions

Section VIII converts the evidentiary record above into forward‑looking predictions. The aim is not advocacy, but anticipation: what institutional actors will do next if the current structure holds. The Washington legislative record supplies enough signal to project behavior across legislation, markets, and litigation.

Governing Dynamic

The governing dynamic is simple. Compass’s strategy relies on controlling when and to whom inventory becomes visible. That control produces value only if opacity survives scrutiny. Once testimony collapses the separation between courts, legislatures, and marketing channels, opacity stops looking like consumer choice and starts functioning as evidence. From that point forward, behavior becomes constrained and predictable.

Near‑Term Legislative Predictions

Late‑Stage Opt‑Out Attempts. If legislative momentum continues, Compass or aligned surrogates will attempt to insert opt‑out language late in the process, framed as seller autonomy or written consent rather than as a structural exception.

Enforcement Reframing. Pressure will increase to move enforcement away from civil‑rights statutes and toward licensing or consumer‑protection mechanisms, not to improve outcomes, but to narrow exposure.

Procedural Delay Tactics. Where outright amendment fails, delay will be used as a substitute—substitutes, narrowing language, or timing strategies designed to preserve private routing through inaction.

Falsifier: No opt‑out language appears, and no procedural delay is pursued across the full legislative cycle.

Market Structure Predictions

If Opt‑Out Survives: Private‑exclusive listings normalize within twelve to eighteen months through form contracts and agent scripting. Inventory fragments, and same‑brokerage buyer representation increases as access routes narrow.

If Opt‑Out Fails: Growth of private exclusives slows or shifts into semantic gray zones—“pre‑marketing,” “coming soon,” or limited‑distribution phases that test the boundary without openly violating the rule.

Seller Outcomes Diverge. Sellers exposed only to networked demand accept offers from constrained pools, while open‑market listings continue to benefit from broader price discovery. The price gap becomes visible over time.

Falsifier: Opt‑out adoption without subsequent inventory fragmentation or increased same‑brokerage transactions.

Litigation and Narrative Predictions

Rhetorical Retrenchment. Compass reduces use of “data scraping” and similar language in formal filings once it becomes clear that those statements can be cited against the company as admissions.

Impeachment via Testimony. Legislative testimony is cited by opposing counsel to challenge standing, market definition, and claimed consumer benefit in federal cases.

Forum Discipline. Executives become less willing to testify live under neutral questioning, with greater reliance on written submissions or sympathetic third‑party witnesses.

Falsifier: Continued use of identical rhetoric across courts, legislatures, and marketing without adverse judicial or legislative response.

Coalition and Spillover Predictions

Opposition Consolidation. Independent brokers and fair‑housing organizations formalize coordination using the Washington record as a template, reducing the effectiveness of narrative repetition in other states.

Cross‑State Replication. Similar legislative battles emerge elsewhere, but move faster as lawmakers reuse the Washington testimony rather than re‑testing the same claims.

Falsifier: Other states repeat the same hearings without materially new evidence or faster resolution.

Forward Lock

If transparency rules hold without opt‑outs, private‑exclusive strategies lose scalability and shift into litigation and branding battles. If opt‑outs persist, private networks entrench before corrective feedback arrives. The decisive variable is not rhetoric or market share, but whether the law allows opacity to default through standard contracts.

Foresight Insight: Once testimony enters the record, future conduct stops being a matter of persuasion and becomes a matter of constraint. What follows is not speculation—it is the next move unless the structure changes.

IX. Conclusion

The importance of the January 2026 Washington hearings lies not in the bills debated, but in what the process exposed. Legislative questioning compelled Compass to explain its business model outside a litigation script, revealing contradictions that cut to the core of its federal antitrust claims.

That pattern will recur as markets consolidate and legislatures scrutinize access-controlling models. Legislative records now operate as antitrust signal, converting narrative inconsistency into evidentiary constraint. Firms that rely on forum-specific explanations of competition will find those narratives increasingly difficult to sustain once testimony enters the public record.

If Compass continues to advance exclusion-based antitrust theories in court while defending opacity before legislatures, future testimony will function less as persuasion and more as impeachment.