MCAI Lex Vision: Judicial Deconstruction of Compass's Narrative Arbitrage v. Zillow

Southern District of New York Validates MindCast AI's Predictive Causal Model

Insight that survives adjudication earns its authority retroactively, through reality rather than reference.

Related publications: How Compass's State Legislative Testimony Undermined its Federal Antitrust Claims , Compass Co‑Conspirator Theory Collapse , The Compass Astroturf Coefficient at the Washington State Senate , HB 2512 and the Collapse of Compass’s Coordinated Opposition , Windermere and Compass, Two Philosophies of Real Estate.

Executive Summary

On February 6, 2026, the Southern District of New York denied Compass’s motion for a preliminary injunction against Zillow in Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc., No. 1:25‑CV‑05201. Judge Jeannette A. Vargas rejected every element of Compass’s antitrust theory—Section 1 conspiracy, Section 2 monopolization, and the underlying claim that Zillow’s Listing Access Standards constituted exclusionary conduct. The court declined to reach irreparable harm, signaling that Compass’s case failed at the level of legal coherence rather than factual contingency.

The ruling matters beyond its immediate procedural effect. Judge Vargas resolved the dispute through structural reasoning that dismantled Compass’s core strategic narratives one by one. She classified Zillow’s Listing Access Standards as lawful platform governance, not exclusionary gatekeeping. She applied the Monsanto/Matsushita framework to reject the conspiracy theory, finding that parallel industry responses to transparency degradation reflected independent action rather than unlawful agreement.

Vargas found Compass’s claimed injury de minimis—48 removed listings out of 429,111—and characterized the harm as self-inflicted: Compass chose a business model that withholds listings from open platforms and bore the foreseeable consequences. And she declined to infer monopoly power despite Zillow’s market share, emphasizing low switching costs, widespread multi-homing, and aggressive entry by well-capitalized competitors.

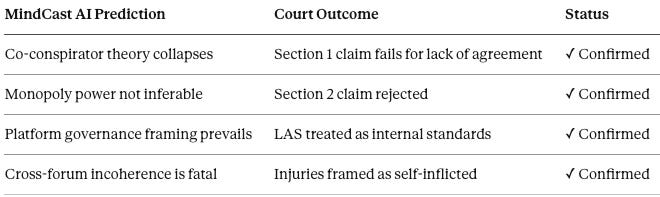

Each of these findings corresponds to a prediction MindCast AI published before the ruling. The co-conspirator theory’s collapse, the failure of the monopoly power claim, the governance characterization of Listing Access Standards, and the fatal effect of cross-forum incoherence—all four outcomes align with the causal architecture MindCast AI articulated months in advance, based on publicly observable structural conditions and institutional reasoning patterns. The court reached its conclusions independently, through its own adversarial process, without reference to MindCast AI’s analyses.

The convergence between a predictive foresight model and an independent federal adjudication represents the strongest form of external validation available: not endorsement, not citation, but structural reconstruction of the same analytical conclusions under adversarial conditions. The central claim of this analysis is straightforward: Judge Vargas did not merely reject Compass’s arguments; she judicially deconstructed Compass’s narrative arbitrage, exposing internal contradictions that courts cannot reconcile.

The implications extend beyond the parties. The ruling constrains Compass’s ability to relitigate the same theory in other jurisdictions, weakens state-level lobbying narratives that depended on federal antitrust framing for their urgency, and establishes persuasive authority that platforms may impose transparency-preserving standards without assuming a duty to accommodate competitors’ preferred business models. For institutional analysts, regulators, and market participants, the opinion confirms that narrative arbitrage—advancing incompatible positions across courts, legislatures, and consumer marketing—can delay outcomes but cannot survive adjudication.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. We specialize in complex litigation, antitrust and national innovation. See State Power vs. Compass Private Exclusives, Foresight on Trial, The Diageo Litigation Validation.

I. The Court Order as an Independent Institutional Lens

The Southern District of New York’s ruling functions as more than a denial of interim relief. It operates as an institutional lens that evaluates Compass’s litigation posture, business strategy, and public narratives against first‑principle antitrust constraints. Understanding how the court framed its task is essential to understanding why MindCast AI’s foresight model aligns so closely with the result.

A. Case and Procedural Context

The procedural posture matters because it set a high bar that Compass nevertheless failed to clear. The court conducted a merits-forward assessment under a heightened standard—not a pleading-stage dismissal or a narrow evidentiary ruling.

Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc., et al., No. 1:25‑CV‑05201 (S.D.N.Y.)

Opinion and Order denying preliminary injunction (Feb. 6, 2026)

Mandatory injunction posture: Compass sought to force Zillow to alter platform rules

Significance: heightened standard + court finds Compass fails even under “serious questions” test

B. Why This Opinion Matters Beyond the Outcome

The opinion matters not because Compass failed to obtain a preliminary injunction, but because the court resolved the dispute at the level of structural logic rather than factual contingency. By declining to reach irreparable harm, the court signaled that Compass’s theory failed at the level of legal coherence.

The ruling therefore creates a durable record that constrains future narrative pivots. Once a court characterizes an asserted injury as self‑inflicted and a challenged policy as lawful governance, subsequent forums inherit that framing.

Judicial signal:

“Because the Court concludes that Compass has not shown a likelihood of success on the merits, it need not reach the question of irreparable harm.” — SDNY Opinion (Feb. 6, 2026)

The court treated the dispute as one of institutional design and competitive structure, not a close factual contest. That posture is precisely what allowed MindCast AI’s foresight model to anticipate the outcome.

II. Core Judicial Findings Relevant to MindCast AI Validation

The court’s opinion resolves Compass’s claims through a series of interlocking findings that collectively dismantle the firm’s strategic narrative. Each finding corresponds to a specific failure mode MindCast AI identified in advance. The following subsections address those findings in the sequence that matters for institutional reasoning.

A. Platform Governance vs. Exclusionary Conduct

At the center of the dispute was whether Zillow’s Listing Access Standards should be understood as exclusionary conduct or ordinary platform governance. The court resolved that question first, and its answer effectively determined the fate of Compass’s claims.

Zillow’s Listing Access Standards (LAS) treated as internal platform governance

Court recognizes Zillow’s discretion to set listing-quality and transparency rules

Compass framed as seeking court-mandated accommodation of its preferred strategy

Core judicial framing: LAS is governance, not gatekeeping—a platform response to transparency degradation, not exclusionary control

MindCast AI alignment: MindCast AI framed this conflict as a contest between coordination infrastructure and extraction strategies. The court’s acceptance of LAS as governance confirms that platforms may impose transparency-preserving rules without assuming a duty to carry competitors’ preferred business models.

By classifying LAS as governance rather than exclusion, the court removed the legal foundation for Compass’s core theory of harm.

B. Co‑Conspirator Theory Rejected

Compass’s Section 1 claim depended on converting parallel industry responses to transparency risk into proof of unlawful agreement. Judge Vargas rejected that move, applying the Monsanto/Matsushita framework and finding that Compass failed to produce evidence that excluded independent action.

The court concluded that independent responses to a shared market condition—namely, the proliferation of private listing networks and NAR’s policy changes—better explained the conduct Compass labeled coordination. Ambiguity, even if suggestive, could not sustain a conspiracy theory. See Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc., No. 1:25‑CV‑05201, slip op. at 29, 33 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 6, 2026).

Once conspiracy was removed from the analysis, Compass’s broader exclusion narrative lost its primary enforcement mechanism.

C. De Minimis Impact and Self‑Inflicted Injury

Compass argued that Zillow’s Listing Access Standards caused substantial competitive harm. The court tested that claim quantitatively and found the impact negligible.

Out of 429,111 new listings added during the relevant period, Zillow removed only 48—approximately 0.011%—for violating LAS. The court treated the impact as de minimis, undermining both antitrust injury and irreparable harm theories. See id. at 41.

The court further characterized any resulting harm as self‑inflicted: Compass chose a business model that withholds listings from open platforms and therefore bears the foreseeable cost of reduced exposure. A preferred strategy’s failure does not constitute cognizable antitrust injury.

The injury Compass asserted flowed from its own strategic choices, not from exclusionary conduct by Zillow.

D. Monopoly Power Not Inferable

Compass’s Section 2 claim required a showing that Zillow possessed durable monopoly power in the online home search market. The court declined to draw that inference.

Although Zillow’s market share fell within a range that can occasionally support monopoly findings, the court emphasized low switching costs, widespread multi‑homing, and recent entry by well‑capitalized competitors. Zillow’s declining share and the rapid growth of rivals like CoStar and Realtor.com confirmed market contestability. See id. at 49–50.

The court’s analysis tracked structural market geometry rather than intent‑based narratives. Compass’s own rhetoric emphasizing consumer choice and flexibility further undermined any claim of foreclosure.

MindCast AI alignment: The outcome matches the prediction that Compass’s own “choice and flexibility” rhetoric would defeat its monopoly claims. The Installed Cognitive Grammar framework anticipated precisely the backfire: by teaching institutions that the market was contestable across legislative and marketing forums, Compass constructed the evidentiary record that foreclosed its own Section 2 theory.

Without monopoly power, Compass’s Section 2 theory collapsed into a dispute over platform preference rather than antitrust law.

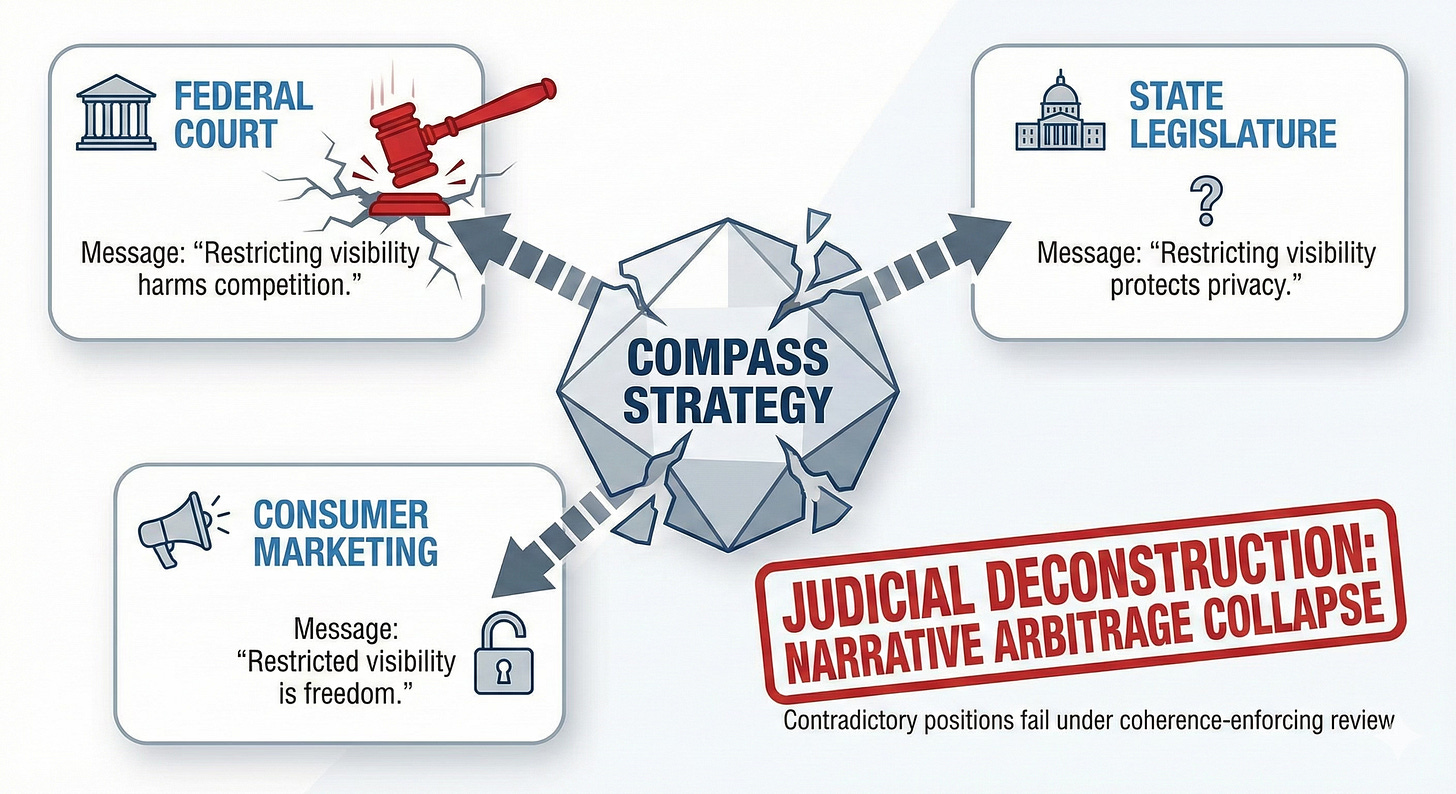

III. Cross‑Forum Incoherence: The Washington Legislative Record

The Washington legislative record reveals why the court found Compass’s litigation posture structurally implausible. Narrative arbitrage fails when positions taken in one forum render positions in another forum incoherent, and courts are sensitive to that inconsistency.

In Washington’s 2025–2026 legislative hearings, Compass and its proxies advanced a consumer-autonomy theory of private listings—framing restricted visibility as homeowner choice and privacy protection. In the SDNY proceeding, Compass advanced the opposite theory: that platform-imposed visibility requirements harm competition and consumer welfare. The two positions do not represent different emphases; they contradict each other structurally. A firm cannot simultaneously argue that restricting listing visibility serves consumers (to legislators) and that requiring listing visibility harms consumers (to courts).

The court did not cite Washington testimony. It did not need to. The self‑inflicted injury finding and the governance framing independently resolve the same contradiction that the legislative record makes explicit. The Washington hearings function as a predictive indicator—evidence that the institutional incoherence was observable in advance—rather than as a legal authority the court relied upon.

The legislative record explains why MindCast AI’s foresight model identified the vulnerability before the court adjudicated it.

IV. Windermere Contrast and Collapse of Collusion Narratives

The Windermere record eliminates the last intuitive basis for a collusion story. When the market participant with the most to gain from private exclusives publicly rejects them, conspiracy narratives lose structural plausibility.

A. Admissions Against Interest in the WA Record

Windermere’s testimony provides an admission against interest that courts find especially persuasive.

Windermere witnesses acknowledged they could profit from private exclusives

Publicly rejected them as harmful to consumers and market integrity

B. Judicial Resonance

The court’s findings align with the structural logic that Windermere’s testimony illustrates. Judge Vargas found no evidence of forced alignment or exclusionary cartel behavior among the defendants—precisely the outcome one would expect when a major market participant voluntarily forecloses its own economic advantage for transparency reasons. When independent actors converge on the same policy position despite divergent financial incentives, the inference of conspiracy becomes structurally implausible. The court’s reasoning reflects this: what Compass characterized as coordinated exclusion, the court recognized as independent responses to shared transparency degradation risk.

MindCast AI alignment: The ruling validates the Compass vs. Windermere Market Philosophy analysis and confirms that self‑disadvantaging transparency advocacy destroys the collusion inference. The Windermere contrast does more than provide useful context; it structurally falsifies the conspiracy theory’s necessary premise.

V. Synthesis: What the Court Validated (Without Citation)

The ruling functions as an external validation checkpoint for MindCast AI’s foresight framework. The court independently adopted the same structural conclusions without reliance on the underlying analyses.

A. Validated Constructs

The following analytical constructs survived adversarial testing through judicial reasoning:

Legislative testimony as a predictive indicator of cross-forum incoherence (Section III)

Platform governance as lawful coordination infrastructure, not exclusionary gatekeeping (Section II.A)

Structural market contestability over intent-based conspiracy narratives (Sections II.B, II.D)

Self-disadvantaging transparency advocacy as a falsifier of collusion theories (Section IV)

B. Foresight Validation Snapshot

MindCast AI published four core predictions before the SDNY ruling. Each addressed a distinct element of Compass’s litigation theory, and each mapped to a specific judicial finding. The table below pairs each prediction with the court’s corresponding holding.

The co-conspirator prediction rested on the Monsanto/Matsushita framework’s requirement that plaintiffs exclude independent action—a threshold Compass’s evidence could not meet. The monopoly power prediction followed from structural market indicators (low switching costs, multi-homing, well-capitalized entry) that made durable dominance implausible regardless of Zillow’s share. The governance prediction tracked the distinction between platform rule-setting and exclusionary conduct—a distinction the court adopted as its organizing framework. And the cross-forum incoherence prediction drew on Compass’s incompatible positions across federal litigation, state legislatures, and consumer marketing, which the court resolved by characterizing the asserted injury as self-inflicted.

No prediction required access to sealed filings or privileged information. Each derived from publicly observable structural conditions and institutional reasoning patterns.

C. What the Convergence Represents

The opinion represents an independent judicial reconstruction of a predictive causal model articulated in advance. That convergence—not agreement, endorsement, or citation—is the form of validation that matters. No claim of judicial endorsement accompanies the alignment; the court reached its conclusions through its own adversarial process. The convergence is structural, not referential.

Four predictions, four confirmed holdings, one independent court. The foresight framework did not require the court's validation to function—but the court's validation confirms that the framework functions.

VI. Implications Going Forward

The SDNY ruling constrains Compass’s strategic options across multiple institutional dimensions. Each constraint reinforces the others, creating a compounding effect that narrative pivots cannot easily overcome.

A. Jurisdictional Foreclosure

Compass now faces a durable federal record characterizing its core theory as legally incoherent. Any attempt to relitigate the same antitrust claims in another federal district invites immediate citation to Judge Vargas’s opinion—not as binding precedent, but as persuasive authority that forces Compass to explain why a different court should reach a different structural conclusion on materially identical facts. The self-inflicted injury finding and the governance characterization of LAS travel with the record. Future defendants in any Compass-initiated antitrust action can point to an opinion that already resolved the threshold questions against the plaintiff.

B. State Legislative Erosion

The ruling weakens Compass’s state-level lobbying posture by removing the federal antitrust scaffolding that gave legislative arguments their urgency. When Compass and its proxies argued in Olympia that platform listing standards constituted coercive monopoly conduct, the implicit claim was that federal antitrust law supported their characterization. A federal court has now rejected that characterization explicitly. Legislators evaluating private-listing protection bills can no longer assume that the underlying competitive-harm theory has legal merit; they must instead evaluate the policy on consumer-welfare grounds alone—terrain where Compass’s position is weakest.

C. Platform Governance Precedent

For platforms beyond Zillow, the opinion reinforces the principle that transparency-preserving standards constitute lawful governance rather than exclusionary control. Any platform that conditions access on listing visibility, data quality, or consumer-facing transparency can now cite a federal court’s reasoning in support of that design choice. The ruling shifts the burden: firms seeking to avoid platform standards must demonstrate exclusionary effect, not merely assert strategic inconvenience.

D. Predictive Infrastructure as Institutional Asset

The alignment between MindCast AI’s pre-ruling analysis and the court’s independent reasoning validates a broader methodological claim: pre-litigation legislative and market analysis, when grounded in structural causal models, can function as predictive infrastructure. Institutions that invest in identifying cross-forum incoherence before adjudication gain actionable foresight—the ability to anticipate not just outcomes, but the reasoning paths courts will follow.

Once narrative arbitrage undergoes judicial deconstruction, reassembly becomes difficult. The institutional record now spans forums, and each forum’s conclusions reinforce the others.

VII. Why Narrative Arbitrage Fails in Courts (And What Trial Would Have Made Explicit)

The case illustrates a general institutional principle: courts function as coherence-enforcing systems. When advocacy fragments across forums, judicial reasoning compresses competing stories back to first principles.

A. Why Courts Deconstruct Narrative Arbitrage

Courts operate as coherence‑enforcing institutions. When advocacy fragments across forums, judicial reasoning compresses it back to first principles.

Courts privilege coherence across forums over tactical storytelling

When a firm advances incompatible definitions of competition, injury, or consumer welfare, courts treat the conflict as a credibility failure—not a close legal question

Judicial analysis stabilizes around first‑principle structures (governance, contestability, entry), not advocacy narratives

Judicial lesson:

A preferred business model’s failure does not constitute antitrust injury

Platform standards that increase transparency are presumptively lawful absent exclusionary control

B. What Trial Would Have Made Explicit (Without Changing the Outcome)

Cross‑examination would have forced Compass to reconcile three incompatible positions:

Federal court: restricting listing visibility harms consumers and competition

State legislatures: restricting listing visibility protects privacy and homeowner autonomy

Consumer marketing: Compass markets restricted visibility as freedom from platforms

The court’s reasoning already resolves this contradiction by treating Compass’s injury as self‑inflicted. Additional evidentiary development would have sharpened, not altered, the court’s conclusions.

MindCast AI insight: Narrative arbitrage can delay outcomes, but it cannot survive adjudication when institutional memory spans forums.

VIII. Conclusion

Judge Vargas resolved Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc. at the level of structural logic. Every pillar of Compass’s antitrust theory failed—not on close factual questions, but on legal coherence. The court classified Listing Access Standards as platform governance, rejected the conspiracy theory under the Monsanto/Matsushita framework, found Compass’s claimed injury de minimis and self-inflicted, and declined to infer monopoly power in a contestable market. By not reaching irreparable harm, the court signaled that Compass’s theory broke at the threshold.

MindCast AI published each of these conclusions before the court reached them, based on publicly observable structural conditions. The court’s independent reconstruction of the same causal architecture—under adversarial conditions, without reference to MindCast AI’s analyses—represents convergence through structural reasoning, not citation or endorsement.

Compass maintained incompatible positions across federal litigation, state legislatures, and consumer marketing. Courts compress that kind of fragmented advocacy back to first principles. When those principles expose structural contradiction, the contradiction becomes the holding. Firms that build litigation strategy on forum-specific storytelling construct the evidentiary record that defeats them.

Appendix: Source URLs

Court Opinion

SDNY Opinion and Order (Feb. 6, 2026), Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc., No. 1:25‑CV‑05201 (S.D.N.Y.):

https://ecf.nysd.uscourts.gov

Appendix A — Prior Predictive Analyses (Published Pre‑Ruling)

The following MindCast AI analyses serve not as authority, but as timestamped evidence that the causal model later reconstructed by the SDNY court appeared in published form before the ruling.

Compass v. Zillow (Early Platform‑Conflict Framing) https://www.mindcast-ai.com/p/compasszillowRelevance: Establishes early identification of platform governance, visibility control, and asymmetric incentives before Washington testimony or federal adjudication.

Zillow’s Response and Platform Governance Logic https://www.mindcast-ai.com/p/zillowreply Relevance: Articulates the governance‑versus‑exclusion distinction later adopted by Judge Vargas; anticipates rejection of boycott and monopoly framing.

Appendix B — Prior MindCast AI Foresight Validation

MCAI Innovation Vision: MindCast AI’s NVIDIA NVQLink Validation

MCAI National Innovation Vision: Foresight Analysis in Illegal GPU Export Pathways (2025–2030)

MCAI National Innovation Vision: The Federal-State AI Infrastructure Collision

MCAI Lex Vision: Foresight on Trial, The Diageo Litigation Validation

MCAI National Innovation Vision: H200 China Policy Validation