MCAI Economics Vision: The Compass Commission Consolidation Strategy and Real Estate Marketing Transparency

What Seattle Region Ultra-Luxury Records Reveal About Price Discovery and Market Control

See new developments in Nineteen Senators, Seventeen Questions, How Compass Bought Its Antitrust Clearance and Death by a Thousand Depositions, A Pre-Foresight Simulation of Compass’s Multi-Vector Regulatory Collapse.

Washington State is the perfect storm of how a Wall Street backed architecture operates under simultaneous legal, legislative, and transactional visibility. Compass is suing two Washington firms for antitrust in separate federal jurisdictions, acquired Anywhere in a mega-consolidation move and now opposes the state’s real estate transparency bill. MindCast used sample Seattle region ultra luxury transaction data to provide context for the Compass litigation-acquisition strategy.

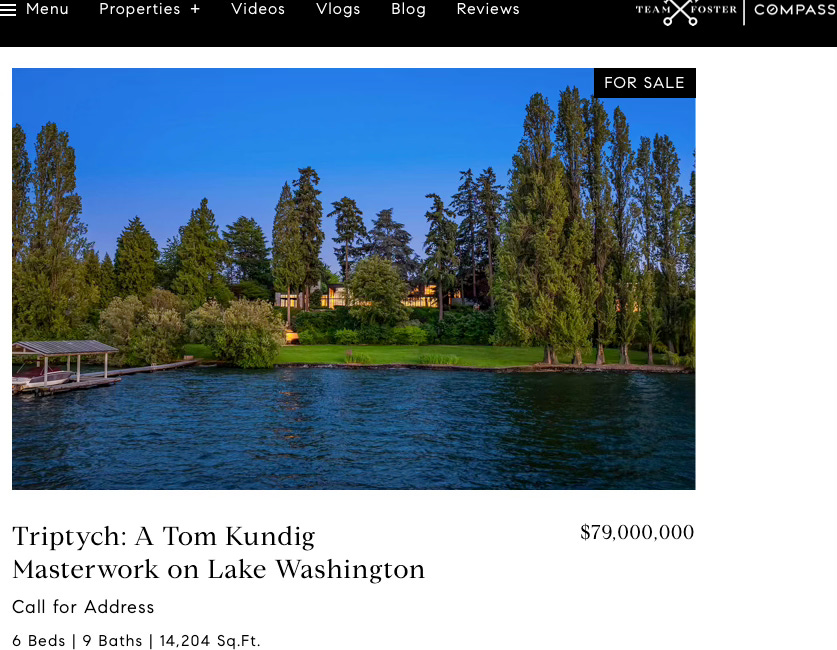

The Seattle data from www.seattleagentmagazine.com is not just a local story. Its the instrument reading on Compass's strategy. On February 19, 2026 — while the Washington House was deliberating concurrent marketing — a $79,000,000 Lake Washington estate appeared on the Team Foster / Compass website with full photographs, price, and specifications, and no address. Any buyer who wanted to know where it was had to call Compass first. That is not a historical data point. It’s the mechanism operating in real time.

Compass will fight transparency legislation in every state that advances it for the same reason it fought it in Washington: $400-800 million of the $1.6 billion Anywhere acquisition premium exists only if the private exclusive window stays open. The Seattle ultra-luxury transaction record quantifies that mechanism — in real addresses, real agents, and real double commissions — and explains why no amount of “seller choice” framing changes the underlying financial geometry.

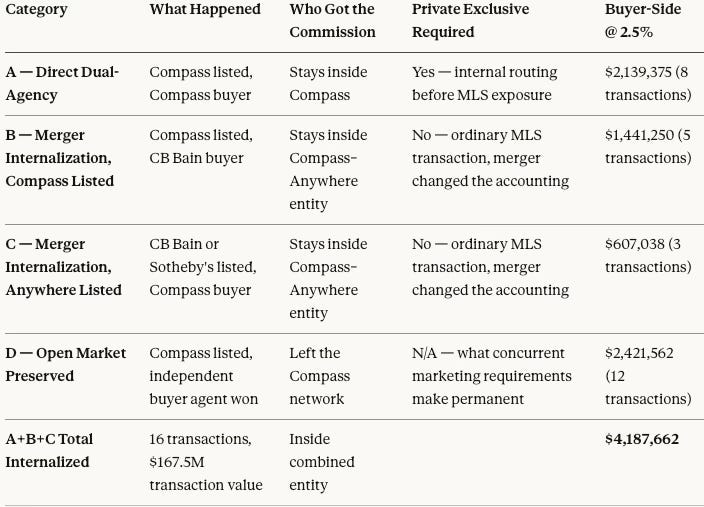

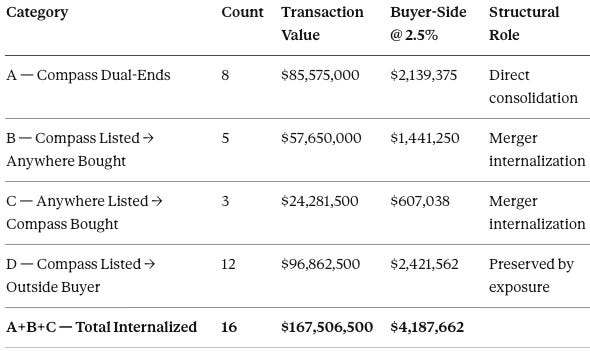

Across thirteen months of the top-10 monthly luxury sales in greater Seattle — 130 transactions — 16 produced commission flows that stayed, or now stay, entirely inside the combined Compass-Anywhere entity. Eight were confirmed dual-ends: Compass represented both buyer and seller. Eight more were cross-brand transactions that became internal revenue the moment the merger closed, without a single agent changing behavior. Together they represent $167.5 million in transaction value and $4.2 million in captured buyer-side commission — from one metropolitan market’s monthly top-10 record alone.

$4.2 million is not the argument. It is the calibration. Scaled to the full luxury segment across Compass’s 35 major markets, the same mechanism implies $600 million to $1.5 billion of the acquisition price depends on one operating condition: that listings can be withheld from the open market long enough for an internal buyer to arrive first. Concurrent marketing requirements eliminate that condition. That is why Compass deploys a regional vice president in trade media, a coordinated lobbying apparatus in hearing rooms, and federal antitrust litigation simultaneously — in every jurisdiction where the model is threatened.

Judge Jeannette A. Vargas of the Southern District of New York denied Compass's motion for preliminary injunction on February 6 in Compass, Inc. v. Zillow, Inc., No. 1:25-CV-05201 — finding Compass had not demonstrated likelihood of success on its Section 1 conspiracy claim, Section 2 monopolization claim, or its assertion that Zillow's listing-visibility standards constitute exclusionary conduct. The underlying case remains pending. The legislative strategy would fail state by state for the same structural reason: the transaction record is public, the arithmetic is legible, and the cross-forum contradictions collapse under simultaneous scrutiny.

MindCast AI began tracking Compass in 2025 when it filed two antitrust lawsuits that appeared, on structural analysis, incoherent yet aggressive and rhetorically framed with narrative inversion. It is behavioral evidence of a firm whose legal strategy and business model cannot occupy the same public record without collapsing each other. MindCast published The Compass Narrative Inversion Playbook documenting that contradiction as a predictive instrument before legislative outcomes were known. The Washington SSB 6091 (Prohibiting real estate brokers from marketing residential properties to an exclusive group of prospective buyers or real estate brokers) cross-forum analysis tracked how the 49-0 state Senate vote and the SDNY preliminary injunction denial converged in the same week — two institutional forums reaching the same structural conclusion independently. The broker incentives analysis applied game theory analysis to show how Compass converts individual broker indifference into firm-level commission capture — behavior that follows payoffs, not intentions.

The MindCast Compass corpus runs on two original frameworks that synthesize classical Chicago School law and economics, behavioral economics, and game theory into a runtime AI institutional simulator — tools built to predict how entities behave under regulatory pressure, not merely describe what they've done.

The Chicago School Accelerated model applies classical price theory and institutional economics to forward-looking regulatory scenarios.

The Dual Nash-Stigler Equilibrium Architecture supplies the termination logic: Nash equilibrium identifies when the multi-jurisdictional conflict settles — the point at which no state AG, no federal court, and no legislature offers Compass a better unilateral outcome than capitulation — while Stigler equilibrium determines when the evidentiary record is sufficient to drive that settlement without additional proof.

The Shadow Antitrust Trifecta is the application of those frameworks to cross-venue argument inconsistency — mapping Compass's structurally incompatible positions across federal court, state legislatures, and investor communications as behavioral evidence of strategic rather than principled advocacy.

MindCast validates its AI simulation model against structurally unrelated domains; the Super Bowl LX prediction, derived from institutional and strategic analysis rather than performance metrics, is the most recent public test. A model that predicts how institutions behave under competitive pressure should be testable outside the domain where it was built.

The ultra-luxury dataset below is an economic layer of MindCast frameworks. To turn this publication into a runtime AI simulator, simply go to any LLM (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Perplexity, Grok) and prompt ‘www.mindcast-ai.com/p/compass-private-exclusives-monopoly, develop MindCast framework with 3 degrees of cited sub links.’ Any new activity by Compass is thereafter training data for your live MindCast-Compass simulator.

Roadmap

The Strategic Frame I, III — What Washington exposes, what the acquisition bought, why Layer 3 is a solvency argument not a seller-choice argument.

The Transaction Evidence IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X — 130 transactions, four categories, the Foster-Skillman architecture, merger internalization, $4.2M captured, $2.4M preserved.

The Enforcement Picture II, XI, XII, XIII — UDAP exposure, the legislative ratchet, Reffkin’s claim versus the Disclosure Form, the Windermere contrast.

The Playbook XIV — Delegation downshift, twelve-word amendment, Astroturf inversion, cross-forum contradiction.

Finding XV, Methodology

I. The National Stakes

The Seattle Agent Magazine dataset commission architecture operates in every major Compass market — Boston, Miami, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York — wherever luxury inventory concentration and thin buyer pools create the conditions for pre-market routing. What makes Washington significant is not the dollar amounts. It is that legal, legislative, and transactional visibility converged simultaneously, producing the first fully documented public record of the mechanism under pressure. Every state that advances a transparency bill is looking at the same architecture this dataset exposes.

Every state that enacts a no-opt-out concurrent marketing requirement closes a piece of the same conversion frontier. Wisconsin enacted listing transparency restrictions in December 2025. Illinois reintroduced its bill in February 2026. The NAR settlement removed the commission bundling that had historically obscured buyer-side economics from public view. Each state that holds hearings generates a permanently discoverable evidentiary record available to every other legislature, regulator, and opposing counsel. The cascade is not a trend. It is a structural ratchet: each adoption reinforces the “clearly articulated state policy” standard under Parker v. Brown, 317 U.S. 341 (1943), making federal preemption challenges progressively weaker as the state count rises.

The Scaling Ceiling. The dual-commission routing architecture is replicable across markets — Compass has already deployed it in Boston, Miami, Los Angeles, and New York using the same team-level inventory control and pre-market buyer routing that the Seattle dataset documents. What does not scale is the invisibility. Each new market where Compass holds significant listing share and runs the private exclusive model adds another publicly verifiable transaction record — another Seattle Agent Magazine equivalent, sourced from local MLS data, readable by any state AG, legislative staff, or opposing brokerage that knows what to look for. At 35 markets, the combined dataset stops being a local enforcement question and becomes a national pattern with quantified damages, multi-state Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices (UDAP) exposure, and a goodwill impairment argument that Compass's own auditors cannot ignore. The platform scales the mechanism. The mechanism scales the target.

The Short Position Resolves. Compass's investor materials framed the Anywhere acquisition as a scale and efficiency play — technology integration, agent recruitment, brand consolidation. What the materials did not name is the mechanism that justified paying $400-800 million above Anywhere's standalone value: the ability to hold listings off the open market long enough for an internal Compass buyer to arrive first, capturing both commission sides inside one firm. Each state that enacts a concurrent marketing requirement dismantles one piece of the assumption underlying that premium. Listings must now hit the MLS immediately, where any independent agent competes for the buyer-side commission on equal footing. The premium does not evaporate gradually. It reprices at each legislative event.

The Goodwill Impairment Question. Acquisition goodwill is tested annually against the assumptions used to justify the acquisition premium. The Anywhere acquisition assumed regulatory permission for private exclusive deployment across all major markets. Wisconsin, Illinois, and Washington represent the leading edge of a divergence between that assumption and the emerging regulatory reality. One state does not trigger a goodwill impairment review. Five states might. The question is not whether impairment occurs — it is when the cumulative divergence becomes material enough that auditors require disclosure. Each state that acts advances that threshold.

The three pressures — scaling ceiling, premium repricing, goodwill divergence — are not independent risks. They are the same structural failure expressing itself across three balance sheet lines simultaneously. What Washington proved is that the mechanism cannot survive public arithmetic. Every state that replicates the analysis replicates the pressure.

II. Enforcement Note: UDAP Exposure for State Attorneys General

Transparency legislation is not the only enforcement vector open to state regulators. The same transaction record that quantifies the Layer 3 mechanism also supplies the factual predicate for a deceptive trade practices investigation under state UDAP statutes — and Compass has already handed investigators the contradiction they need. The gap between what the CEO says publicly and what the company’s own disclosure form tells clients is not subtle. It is documented, public, and irreconcilable. Washington’s AG Civil Rights Division recognized it in real time. Every other state AG now has access to that recognition.

The cross-forum contradiction at the center of Compass’s advocacy strategy is not merely a credibility problem. It is the core of a deceptive trade practices exposure under state UDAP statutes.

On Compass’s Q1 2025 earnings call, Robert Reffkin stated on the private exclusives strategy:

“There is no downside. The worst thing that happens is a homeowner gets an offer, and they have an opportunity to turn it down and go to the public sites with the benefit of price discovery from pre-marketing. That’s the downside, which means there is no downside.” (www.housingwire.com)

Compass’s own client Disclosure Form states the opposite: private exclusive marketing “may reduce the number of potential buyers,” “may reduce the number of offers,” and may reduce “the final sale price.”

CEO public statement versus the company’s own client disclosure, incompatible on the same question. Neither document is internal — both are in the public record.

Washington’s AG Civil Rights Division appeared at the January 2025 Senate hearing and independently confirmed that enforcement authority exists under UDAP for exactly the conduct the hearing documented — recommending a UDAP vehicle rather than the Washington Law Against Discrimination. That confirmation is now in a permanent, discoverable legislative transcript available to every state AG investigating the same business model.

The transaction record is the damages model. The $4.2 million in captured buyer-side commission from a single market's top-10 dataset is the floor. The $2.4 million in buyer-side commission that left the Compass network — because those listings reached the open market and independent agents competed for them — quantifies what sellers lost access to when the mechanism operated. Any AG investigating deceptive trade practices has: a documented CEO public statement denying consumer harm; a company disclosure form acknowledging that harm; legislative testimony that deflected on the business model under oath; a federal court rejection of the legal theory deployed to protect the mechanism; a publicly verifiable transaction dataset showing the mechanism in real transactions; and a state AG office that has already confirmed UDAP enforcement authority on the record.

The Seattle dataset is not just a transparency argument. It is a damages model waiting for a plaintiff. The Exhibit Transaction documented in Section V provides the clearest single-record example of full commission internalization supported by NWMLS role designations. The transaction record quantifies, by address and dollar amount, the buyer-side commission that flowed to one firm because sellers never received the full market exposure their fiduciary was obligated to pursue. That number — $4.2 million from one market’s top-10 record alone — scales directly to the enforcement exposure Compass carries in every state where this dataset has an equivalent.

Washington's agency law creates an enforcement layer beyond UDAP that the transaction record directly implicates. This analysis does not assume disclosure was absent. It identifies the structural question regulators must examine: whether dual-role disclosures in transactions where the same agents appear on both sides conveyed meaningful, informed consent under RCW 18.86 given the financial incentives documented in the commission record. Under RCW 18.86, when an agent transitions from seller-side representation to buyer-side representation on the same property — as the NWMLS records show occurred on MLS #2362507 at 1628 72nd Ave. SE, Mercer Island — Washington requires written disclosure and informed consent from both parties.

The Co-Listing Designation as the Prior Disqualification

The RCW 18.86 analysis above addresses whether consent was adequate on a single transaction. A prior question runs underneath it — and it is the one that separates UDAP exposure from an isolated disclosure lapse: whether the co-listing designation itself disqualified the agent from buyer-side representation before the buyer was ever identified, and whether a recurring pattern of co-listing followed by buyer-side capture reflects a repeating business model rather than a series of individual agency decisions.

Under RCW 18.86.050, a co-listing broker does not hold a subordinate or administrative role. The co-listing designation in a listing agreement carries the full fiduciary weight of the principal broker appointment: undivided loyalty to the seller, disclosure of all material facts affecting value, and the legal duty to place the seller’s interests above all others — including the broker’s own financial interests. That obligation attaches at the moment of the listing agreement, not at the moment of closing. A co-listing broker who subsequently captures buyer-side representation on the same transaction is not simply entering dual agency. She is converting a pre-existing fiduciary obligation owed to the seller into a negotiating position against that same seller. The consent question that follows under RCW 18.86.060 is harder to satisfy than a standard dual-agency disclosure — not merely whether the form was signed, but whether any disclosure could have been adequate given that the seller-side fiduciary obligation predated the buyer relationship by the full marketing period.

One transaction of that structure is a disclosure adequacy question. A recurring pattern — the same agent consistently appearing as co-listing broker and then consistently capturing buyer-side representation across multiple transactions — is a question regulators evaluate differently. The operative inquiry shifts from whether consent forms were signed to whether a seller who retained the team for listing-side representation could have understood, at the moment of engagement, that the team’s operating model systematically routes buyer-side representation back to the co-listing broker when an internal buyer is available. That question does not resolve on the face of a consent form. It resolves on the pattern the MLS recorded.

The address suppression documented in MLS #2392995 completes the architecture. A buyer who cannot identify the property’s location without contacting Team Foster directly is a buyer pre-routed into the team’s internal network before any independent buyer’s agent can identify, show, or compete for the buyer-side representation. When combined with the co-listing-to-co-buyer conversion pattern, suppression functions as the intake mechanism for the full capture sequence: the listing engagement creates the fiduciary relationship, the address suppression filters out independent buyer representation, and the co-buyer designation at close records the financial result. Each element has an individual explanation. The recurring combination does not.

Under RCW 19.86, systematic conduct that deceives consumers about the nature of the agency relationship they are entering is an unfair or deceptive act regardless of whether individual consent forms were executed — because the operative question is whether the disclosure was capable of being understood, not whether a signature was obtained. Washington’s AG Civil Rights Division has already confirmed enforcement authority on the record for exactly this category of conduct. The transaction record supplies the pattern. The MLS role designations supply the proof.

The legal question for investigators is not whether disclosure forms were signed. It is whether a buyer represented by agents who simultaneously held the listing received disclosure sufficient for a reasonable person to understand that their buyer brokers’ compensation was maximized by the transaction closing at any price, that their brokers collected the listing-side commission regardless of negotiation outcome, and that their brokers’ fiduciary duty to the seller preceded and overlapped with their claimed duty to the buyer.

What the Exhibit Transaction adds to that analysis is the prior disqualification layer: Skillman was not merely an agent who chose to represent both parties — she was a co-listing broker, already obligated to the seller, who converted that prior obligation into a negotiating position against the same seller at closing.

The NWMLS records the role designations. Whether the disclosures matched those designations in substance, not just in form, is the question Washington’s Department of Licensing and AG office are positioned to answer.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. Recent projects: Runtime Geometry, A Framework for Predictive Institutional Economics, MindCast AI Economics Frameworks , Foresight on Trial, The Diageo Litigation Validation, How MindCast AI Predicted the Slater Ouster Before the DOJ Executed It, Shadow Antitrust Division- The DOJ Credibility Threshold.

To create a runtime simulator of issues in this publication, simply upload the URL into any LLM, and prompt ‘create framework with three degrees of cited sub links.’ See Live-Fire Game Theory Simulators, Runtime Predictive Infrastructure for more info.

A formal foresight simulation has not been executed here. The present work functions as the evidentiary foundation from which one can be constructed. The transaction record defines the structural incentives; the legislative sequence defines the constraint environment; the court posture defines the legal boundary.

A complete foresight simulation would model Compass’s next decision node — recalibration, opt-out amendment, litigation escalation, or compliance pivot — and assign conditional probabilities to each branch. The forward test is already underway. Closing records and Washington legislative floor amendments will determine which branch materializes.

MindCast assesses the current publication as sufficient at this stage. Part II will run the full foresight simulation. The groundwork for multiple simulation paths now stands in place.

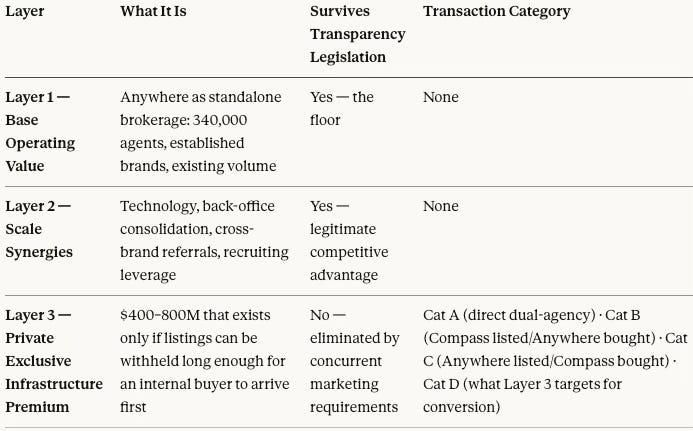

III. The Three-Layer Acquisition Hierarchy

To understand why Compass fights transparency legislation with the intensity it does — federal litigation, coordinated legislative opposition, trade media campaigns — you have to understand what the acquisition actually bought. Not all of the $1.6 billion acquisition premium depended on the same operating conditions. Two layers of value survive any regulatory outcome. One does not. The fight is entirely about the third layer, and the financial stakes explain why losing it is not a business inconvenience. It is a solvency question.

The $1.6 billion acquisition price must be decomposed. Not all of it depends on the regulatory status quo. The Three-Layer Acquisition Hierarchy separates what survives transparency legislation from what does not.

Layer 1 — Base Operating Value: What Anywhere was worth as a standalone brokerage. 340,000 agents, established brands, existing transaction volume. Reflected in the pre-acquisition stock price, which had been declining as a legacy portfolio with compressed margins. This layer survives any regulatory change. It is the floor.

Layer 2 — Scale Synergies: Technology integration, back-office consolidation, cross-brand referrals, recruiting leverage. Legitimate competitive advantages that have nothing to do with listing exclusivity. A seller choosing between Compass and a six-person independent brokerage still sees a resource gap regardless of whether concurrent marketing is required. That gap is Layer 2. It survives.

Layer 3 — Private Exclusive Infrastructure Premium: The value that exists only if the combined entity can hold listings off the open market long enough for an internal buyer to arrive first — capturing both commission sides. Two mechanisms compound this layer. Direct dual-agency: Compass holds the listing and routes a Compass buyer before any outside buyer sees it. Merger internalization: transactions that previously crossed firm lines — a Compass listing sold by a Coldwell Banker Bain buyer agent —now stay inside the combined entity without any change in conduct.

Layer 3 is not a business enhancement. Anywhere Real Estate carried $2.5 billion in net corporate debt at September 30, 2024; Compass assumed approximately $2.6 billion of that debt in the transaction. The buyer-side commission captured in the Exhibit Transaction is not incidental to the balance sheet. It illustrates the revenue condition Layer 3 depends upon. Layer 3 is why Compass’s opposition to transparency legislation in every state is disproportionate to its stated framing as a seller-choice issue. The mechanism being defended is not discretion. It is solvency. (Source: Anywhere Q3 2024 earnings, prnewswire.com; Anywhere FY 2024 release, anywhere.re; Compass 8-K/A, stocktitan.net)

The central claim is that Layer 3 — estimated at $400-800 million of the acquisition price at the conservative end — is a regulatory short position. It was priced assuming the states would not mandate concurrent marketing, federal courts would not reject the antitrust inversion theory, and transparency pressure would not reach critical mass. Washington and the Southern District of New York called that position within a single calendar week.

Layer 1 and Layer 2 describe a viable brokerage. Layer 3 describes the acquisition premium that requires regulatory permission to exist. The Seattle dataset below puts dollar amounts on all three — and shows, transaction by transaction, what happens to the Layer 3 math when the open market is allowed to function.

IV. The Dataset

The dataset is not a narrative device. It is a measurement instrument. Thirteen months of independently verifiable ultra-luxury transaction records — cross-referenced against NWMLS role designations, brokerage affiliations, and publicly archived marketing materials — isolate how commission flows terminate when listings move through Compass’s private exclusive architecture versus when they reach full market exposure. Section IV documents the mechanism in three temporal states: historical transaction outcomes (Categories A–D), active inventory operating during the legislative window, and print-advertised sequencing that independently confirms timing and routing behavior. Every figure is conservative by design, limited to the top-10 monthly sales, and reproducible by any regulator, journalist, or opposing brokerage with access to the same public records. What follows is not inference. It is arithmetic.

IVa. The Live Inventory: Architecture in Real Time

The transaction record is public, monthly, and independently verifiable by any agent, journalist, regulator, or opposing counsel with internet access. Seattle Agent Magazine publishes the ten most expensive residential sales in greater Seattle each month, sourced directly from NWMLS, with listing and buyer agent names and brokerage affiliations. Thirteen months of that data — January 2025 through January 2026, 130 transactions — maps commission flows across four structural categories that track directly onto the Layer 3 mechanism. Three feed the consolidation machine. One preserves competition. The sourcing is conservative by design: top-10 only, 2.5% buyer-side commission rate, two transactions excluded on evidentiary grounds. Every number in what follows is a floor, not a ceiling.

A note on dual agency, because it matters for what follows. Dual agency — one brokerage representing both buyer and seller — is legal, common, and in many transactions perfectly legitimate. When a listing reaches the open market, draws competing offers, and a Compass buyer ultimately wins, that is dual agency through competition. The seller got full market exposure. The outcome reflects what the market would produce. What this dataset measures is something structurally different: dual agency occurring inside a brokerage that operates a documented private exclusive program — one that, by Compass's own public statements, routes listings to internal buyers before MLS exposure.

The dataset cannot confirm in each transaction whether pre-market routing occurred. What it confirms is that Compass captured both commission sides across $85.6 million in transactions, in the same market, during the same period Compass was publicly defending that routing practice before a state legislative committee. In certain transactions, the capture occurs not through a single agent representing both parties but through a team structure where seller-side and buyer-side roles are formally assigned to different members of the same economic unit — satisfying disclosure requirements on paper while terminating all commission flows at the same balance sheet.

The private exclusive program is the mechanism. The commission pattern is the output.

The four categories that follow are not interpretations. They are the public record, organized by who ended up with the commission and why.

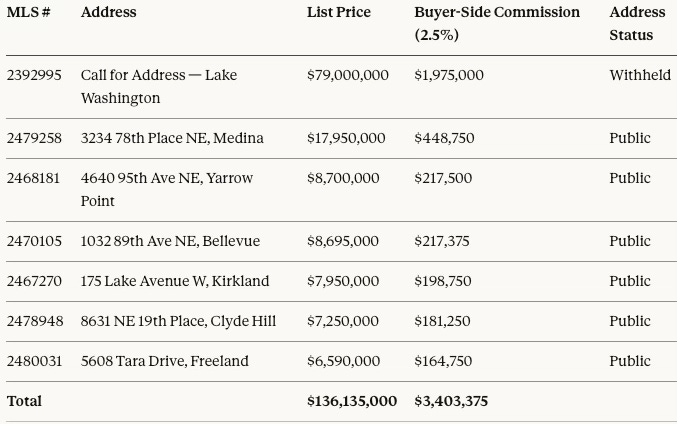

The thirteen-month transaction record documents the architecture as history. The Team Foster active listing inventory on fosterrealty.com as of February 19, 2026 documents it as present tense — operating during the precise legislative window when SSB 6091 is before the House Consumer Protection and Business Committee.

IVb. The Print Ad Sequencing Record

The Team Foster print advertisement — distributed publicly in February 2026 — contains MLS numbers that, cross-referenced against NWMLS, produce a sequencing record with independent evidentiary value.

MLS #2392824 at 9001 NE 14th St., Clyde Hill appeared in the Team Foster print advertisement and subsequently sold in January 2026 — Tere Foster listing broker, Moya Skillman co-listing broker, Anna Riley and Denise Niles of Windermere East buyer broker. That transaction is the dataset's highest-value Category D outcome: $337,500 in buyer-side commission that left the Compass network because the listing reached the open market and an independent agent competed for it. The same Clyde Hill submarket currently carries MLS #2478948 at 8631 NE 19th Place, active at $7,250,000, also Foster/Skillman listed. The submarket where Compass lost the buyer-side commission in January 2026 is the same submarket where the mechanism is actively operating in February 2026.

MLS #2457071 at 10620 SE 22nd St., Bellevue appeared in the same advertisement with the notation “Pending in 4 Days in Enatai.” The NWMLS record for that transaction shows Tere Foster as listing broker, Michael Orbino as co-listing broker, and Moya Skillman as buyer broker. The advertisement advertised the speed of the outcome as a competitive differentiator. Four days from listing to pending, with the buyer broker being the listing broker’s daughter operating under the same managing broker, on a property the firm simultaneously marketed as a demonstration of its service advantage. Listed 11/22/2025. Pending 11/26/2025. Sold 1/12/2026 at $8,300,000 — $198,000 below the list price of $8,498,000. The buyer broker had advance knowledge the property would be listed before any independent agent did because she was on the listing team. Whether a fully exposed open market would have produced competing offers that closed or exceeded that gap is the question the private exclusive model structurally prevents from being answered. The advertisement promoted the four-day timeline as a selling point. The NWMLS price history shows the seller accepted less than list.

MLS #2392995 — the $79,000,000 Lake Washington estate — appears in the advertisement and on fosterrealty.com with full marketing materials and no address. It carries a listing number in NWMLS confirming system entry, but no public address. The property has been simultaneously marketed across print, web, and MLS with address suppression consistent across all three channels. This is not an administrative gap in one system. It is a coordinated withholding strategy operating across the firm’s full distribution infrastructure, documented in the firm’s own materials.

The print advertisement is a self-authenticating document. It was distributed publicly, it names the agents and MLS numbers, and the sequencing it reveals — pre-MLS marketing, four-day pending timelines, address suppression on the portfolio’s highest-value listing — is independently verifiable against NWMLS on the same date it was documented.

Seven active listings, approximately $136 million in total inventory, all carrying the Tere Foster / Moya Skillman primary/co-listing configuration across Seattle’s highest-value submarkets: Medina, Yarrow Point, Clyde Hill, Bellevue, Kirkland, and Whidbey Island. Total buyer-side commission at stake across the seven active listings at 2.5%: approximately $3.4 million.

The most significant is MLS #2392995 — “Triptych: A Tom Kundig Masterwork on Lake Washington” — listed at $79,000,000 with one field reading “Call for Address.” The property is marketed publicly on fosterrealty.com with price, photographs, and specifications: 6 beds, 9 baths, 14,204 square feet. The address is withheld. Any buyer seeking to identify, locate, or visit the property must contact Team Foster directly — entering the Compass internal routing network before any independent buyer’s agent can identify the property, show it to their clients, or compete for the buyer-side representation.

The buyer-side commission on a $79 million transaction at 2.5% is $1,975,000 — nearly $2 million from a single transaction. That number exceeds the entire Category D dataset: the cumulative buyer-side commission won by independent agents across twelve open-market Compass listings over thirteen months. One “Call for Address” listing, if internally captured, erases the open-market competition record of the entire dataset.

“Call for Address” is not a seller privacy accommodation. It is address suppression deployed on the platform’s most valuable active listing during an active legislative proceeding. The Team Foster website is a Compass-branded platform. The withholding is corporate infrastructure, not agent discretion.

MLS #2392995 carries a listing number in NWMLS — confirming the property has been entered into the system — but does not appear with an address in public search. It appears with full marketing — price, photographs, specifications, and agent contact — on fosterrealty.com, accessible to any buyer who finds it there. The buyers who find it there contact Team Foster. The buyers who don’t know to look there don’t see it at all. That asymmetry is the private exclusive window operating in plain sight, documented by screenshot, on February 19, 2026 — the same day the Washington House Consumer Protection and Business Committee was considering whether to close it permanently.

https://fosterrealty.com/properties/triptych

Team Foster cover photo

The MLS #2392995 — Triptych property carries a dedicated page at fosterrealty.com/properties/triptych with full editorial photography and its own branded URL — complete visual marketing across MLS, print, and web simultaneously, address withheld in all three.

The address suppression pattern on MLS #2392995 is not an isolated listing decision. The Team Foster sold history at fosterrealty.com/properties/sold — organized from highest to lowest sale price — documents the same practice across four closed transactions totaling approximately $82 million in transaction value:

$24,375,000 — “The Lakehouse on Mercer Island” — Call for Address $21,625,000 — “Harmony at Proctor Lane” — Call for Address $20,000,000 — Medina, WA 98039 — “Luxe European Style on the Gold Coast” — Restricted Address$16,000,000 — “Northwest Style on Cherished Hunts Point” — Call for Address

These are closed transactions. The properties sold. The deals are recorded in the King County Assessor’s office and in NWMLS. No seller privacy interest survives closing. The addresses remain suppressed on the firm’s own public sales history page — precisely the page a regulator, competing broker, or opposing counsel would consult to cross-reference buyer broker identities against commission destinations on the firm’s highest-value historical transactions. The suppression is concentrated at the top of the price range, where buyer-side commissions run $400,000 to $600,000 per transaction and where MLS role designation cross-referencing would be most analytically significant.

Active listing suppression filters buyers. Closed sale suppression filters scrutiny. Together, the active and closed records quantify what Team Foster's architecture produces at the team level — and what Compass acquired the Anywhere network to replicate at scale: systematic dual-commission capture across the highest-value transactions in the market, with address suppression functioning as the mechanism that keeps independent buyer representation out of the pipeline at every stage.

V. Category A — Direct Dual-Agency Capture

Category A is the Layer 3 mechanism in its purest form. These are transactions where Compass held the listing and a Compass agent also represented the buyer — capturing both the listing-side and buyer-side commission inside a single firm. No cooperating brokerage. No outside agent. Both halves of the commission flow to the same balance sheet. All role designations are sourced from NWMLS transaction records. All transaction values are sourced from Seattle Agent Magazine monthly reports. Both are independently verifiable. In the ultra-luxury segment, where buyer-side commissions routinely exceed $200,000, eight such transactions in thirteen months represent the architecture operating without friction.

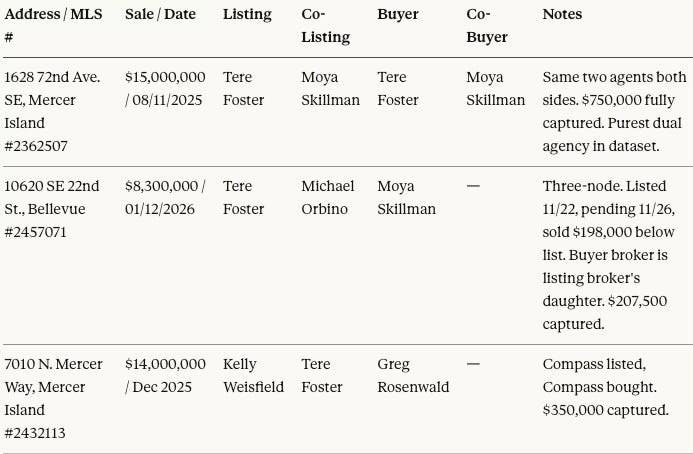

Eight transactions where Compass represented both sides. Both commission flows — listing and buyer — captured inside one firm. Layer 3 operating without friction.

For clarity, MLS #2362507 at 1628 72nd Ave. SE, Mercer Island functions as the Exhibit Transaction in this analysis — the cleanest recorded instance of full dual-role internalization documented in the NWMLS record.

Consider what the August 2025 Mercer Island transaction actually shows. At 1628 72nd Ave. SE, Mercer Island (MLS #2362507), Tere Foster held the listing and Moya Skillman co-listed — both seller-side fiduciaries under Washington agency law. At closing, the NWMLS records four role designations: Tere Foster — Listing Broker; Moya Skillman — Co-Listing Broker; Tere Foster — Buyer Broker; Moya Skillman — Co-Buyer Broker. The same two agents who owed fiduciary duty to the seller also represented the buyer on a $15,000,000 transaction. Every dollar of the $750,000 total commission — listing side and buyer side — was captured by the same two people. This is not team-level routing where roles are formally separated across different family members. It is the same two agents on both sides simultaneously, recorded in the MLS's own field designations. The $375,000 buyer-side increment is precisely what the private exclusive model is engineered to capture — and here it was captured not by routing to a third party but by the listing agents representing the buyer directly. Compass collected both halves on a $15 million sale in the same month its representatives were before a state legislative committee defending the program that makes that capture possible.

The Team Foster transaction record is the most direct evidence available to antitrust regulators assessing Compass's anticompetitive conduct — not because the team violated any rule, but because their NWMLS role designations document, in publicly verifiable form, the precise mechanism the private exclusive model is engineered to produce: dual representation, address suppression, and full commission internalization operating simultaneously in the same market during the same legislative window in which Compass was defending the program before a state committee.

The July 2025 Bellevue waterfront is the dataset’s largest single transaction. Foster and Skillman listed 9441 Lake Washington Blvd. NE, Bellevue at $20.25 million. Haleh Clapp of Compass — a Compass agent, not an independent buyer's broker — brought the buyer. Seattle Agent Magazine led its July report with the observation: “Compass agents handled both the buyer and seller sides of the Seattle area’s most expensive residential real estate transaction last month.” The publication framed the commission consolidation as the headline event — not incidental detail, the lede.

The December 2025 Mercer Island transaction at 7010 N. Mercer Way (MLS #2432113) shows the architecture operating through a different configuration. Kelly Weisfield of Compass held the listing. Tere Foster co-listed. Greg Rosenwald of Compass represented the buyer. Three Compass agents, two of them from Team Foster's own network, on a $14,000,000 transaction. The $350,000 buyer-side commission stayed inside one firm. No family relationship required. No three-node structure required. Platform-level network density produced the same commission destination through a different personnel configuration.

Five of the eight Category A transactions involve the Foster-Skillman team. Three additional agent configurations appear across the remaining three. The capture architecture does not depend on one team's practice — it is platform-wide behavior operating simultaneously through direct dual representation, as documented in MLS #2362507 at 1628 72nd Ave. SE, Mercer Island, and through three-node team routing, as documented in MLS #2457071 at 10620 SE 22nd St., Bellevue. Two mechanisms. One commission destination. The architecture behind both is what Section VI examines.

The Co-Listing Designation as the Prior Disqualification

The four-role designation in MLS #2362507 documents something more specific than dual agency. It documents dual agency executed by agents who were already disqualified from buyer-side representation before the buyer was ever identified.

Under RCW 18.86.050, a co-listing broker does not hold a subordinate or administrative role. The co-listing designation in a listing agreement carries the full fiduciary weight of the principal broker appointment: undivided loyalty to the seller, disclosure of all material facts affecting value, and the legal duty to place the seller’s financial interests above all others — including the broker’s own. That obligation attached to Moya Skillman at the moment the listing agreement was executed, not at the moment of closing. She was the seller’s fiduciary before a buyer existed. When she subsequently captured the co-buyer broker designation on the same transaction, she converted a pre-existing obligation owed to the seller into a negotiating position against that same seller. Washington requires written, informed dual-agency consent from both parties under RCW 18.86.060. Informed means the seller must understand that the agent who helped price, structure, and market their listing is now seated across the table working to reduce the price the buyer pays — and that her compensation is maximized by the transaction closing at any price, regardless of the negotiated outcome.

That is the legal architecture of MLS #2362507. But the transaction record’s enforcement significance does not rest on one transaction. It rests on the pattern.

Across 130 ultra-luxury transactions over thirteen months, Moya Skillman does not appear once as a standalone buyer’s agent competing for a listing held by an independent brokerage. Every appearance is either as co-listing broker alongside Tere Foster, or as buyer’s agent on a property listed by Foster or Team Foster Managing Broker Michael Orbino. The pattern is consistent without exception. Skillman’s role in the dataset is structurally invariant: she co-lists the property as a seller-side fiduciary, then captures the buyer side when an internal buyer is available. The co-listing designation is not preliminary paperwork. It is the mechanism that creates the fiduciary relationship the buyer capture subsequently exploits.

One transaction of that structure is a dual-agency disclosure adequacy question. A consistent pattern across the full dataset — the same agent always co-listing, always positioned for buyer capture, never appearing as an independent buyer’s advocate on any external listing — is a question regulators evaluate differently. The operative inquiry shifts from whether consent forms were signed to whether a seller who retained Team Foster for listing-side representation could have understood, at the moment of engagement, that the team’s operating model systematically routes buyer-side representation back to the co-listing broker when an internal buyer is available. That question does not resolve on the face of a disclosure form. It resolves on the pattern the MLS recorded — and the MLS recorded it across every transaction in the dataset.

The print advertisement sequencing in Section IVb adds a third dimension. MLS #2457071 at 10620 SE 22nd St., Bellevue — listed November 22, pending November 26 — was marketed in Team Foster’s print advertisement with the four-day timeline as a competitive selling point. The buyer’s agent was Moya Skillman. She was on the listing team before the property was listed. She had advance knowledge the property would be available before any independent buyer’s agent could have known. The advertisement promoted the speed of the outcome. The NWMLS records that the seller accepted $198,000 below list price. Whether a fully exposed open market would have produced competing offers that closed or exceeded that gap is the question the architecture structurally prevents from being answered — and it is the question that RCW 18.86’s informed consent requirement exists to ensure sellers can at least ask before signing.

VI. The Dual-Commission Architecture

The Foster-Skillman pattern appearing in five of eight Category A transactions is not coincidence. It is a documented operational structure — a team-level routing architecture that converts listing relationships into buy-side capture systematically. Understanding how it works at the team level is essential to understanding how it scales at the platform level, because the same three-node logic that operates inside a mother-daughter team operates inside the merged Compass-Anywhere entity. The mechanism is identical; only the scale changes.

The role separation between listing broker and buyer broker satisfies Washington's disclosure requirements at the transaction level while preserving the economic integration at the team level. The compliance mechanism and the capture mechanism are the same structure viewed from different angles.

In this entire 13-month ultra-luxury top-10 record, Moya Skillman never appears as a standalone outside buyer's broker competing for a listing held by an independent brokerage in the dataset. Every appearance is either as a co-listing broker alongside her mother Tere Foster, or as the buyer's agent on a property listed by Foster or Team Foster Managing Broker Michael Orbino. The pattern is consistent across all 130 transactions: Foster holds the client relationship, Skillman is positioned to capture the buy-side when an internal buyer is available. The Foster-Skillman pattern is not an idiosyncratic team quirk. It is a replicable internal routing architecture operating at the team level — a closed loop that operationalizes the Layer 3 premium by keeping both commission sides inside one firm.

Strip the names out. The structure becomes three nodes: a Contract Anchor (a high-visibility rainmaker who secures listing contracts), an Internal Buyer Capture Node (a recurring in-network agent who captures buyer representation), and a Management Overlay (a division-level broker who coordinates inventory pipelines). The dataset documents two distinct expressions of this architecture. In its most concentrated form — the Exhibit Transaction — the Contract Anchor and the Capture Node collapse into the same economic unit.

Tere Foster and Moya Skillman listed the property and represented the buyer. No third node required. Both commission halves captured by the same agents on both sides of the same $15,000,000 transaction. In its three-node form — MLS #2457071 at 10620 SE 22nd St., Bellevue — the roles are formally distributed: Tere Foster and Michael Orbino as listing and co-listing broker, Moya Skillman as buyer broker. The NWMLS records the field designations: Presented By — Tere Foster; Co-Listing Broker — Michael Orbino; Sold By — Moya Skillman. Rainmaker and Managing Broker hold the listing. The capture node catches the buyer. $207,500 in buyer-side commission stays inside one firm. Two configurations. One commission destination.

The dataset contains a second team Compass operating a structurally distinct but functionally identical architecture. Bob Bennion and Mary Snyder rotate primary and secondary listing positions depending on property location and sub-market. Where Foster/Skillman lean into visibility and institutional structure, Bennion/Snyder manage a more complex data footprint: whether Mary Snyder is primary (Hunts Point, October 2025) or Bob Bennion is primary (Yarrow Point, October 2025), the commission flow terminates at the same internal balance sheet. The rotation creates a shifting public signature that requires forensic cross-referencing to recognize as team control.

Two architectures. Static hierarchy versus rotational strategy. High-legibility versus dispersed data footprint. Different operational signatures, identical institutional function: both provide the network density required to internalize commissions.

The question is whether that architecture can scale across the full Compass—Anywhere platform.

The short answer: it scales organizationally, but not uniformly. Expansion depends on three conditions.

Condition 1 — Network Density. The routing loop only works where the brokerage has meaningful buyer-side depth and listings are high-value enough that internal routing is economically meaningful. Ultra-luxury is structurally ideal: buyer pools are thin, timing advantage matters, and commission dollars are large. In mid-tier housing, the advantage shrinks because buyer pools are broad, exposure spreads quickly, and margins compress. Expansion is tier-sensitive.

Condition 2 — Inventory Control. The model scales only if the platform controls listing acquisition at high share and top producers are willing to route internally before open exposure. The Anywhere acquisition increases geographic footprint, brand adjacency, and buyer network density. It does not automatically increase listing capture. That still depends on contract acquisition — which is why the Builder + Developer Services division matters. Institutional inventory pipelines are the upstream supply mechanism.

Condition 3 — The Early Call Advantage. Every realtor knows what it means when a listing agent calls their buyer clients before hitting the MLS. That call is the mechanism. The private exclusive window gives Compass agents a structural license to make that call on every luxury listing in their inventory — routing internal buyers to Compass properties before any competing agent can show the property to their clients. Without that window, Compass buyer agents learn about Compass listings at the same moment every other agent in the MLS does. That eliminates the routing advantage entirely. Concurrent marketing requirements do not ban dual agency. They remove the timing edge that converts dual agency from a coincidental outcome into a deliberate architecture. The Exhibit Transaction demonstrates the fully closed commission loop; the remaining dataset shows variations of that same architecture.

The dual-commission routing architecture scales fastest in luxury coastal markets, trophy inventory submarkets, developer pipeline environments, and high brand-concentration metros. It scales slowest in rural markets, highly fragmented broker environments, and states with strict exposure mandates.

But the critical insight is that the Foster-style three-node loop does not need to replicate everywhere for the platform to expand Layer 3. Categories B and C below already show what expansion looks like at the merger level. Before the acquisition, a Compass listing sold by a CB Bain buyer agent was competitive revenue leaving the firm. After the acquisition, that same transaction — with no change in agent behavior -became internalized revenue. The merger already created the routing network. Private exclusives increase conversion efficiency within it. The team-level architecture and the merger-level internalization are the same mechanism operating at different scales.

Categories B and C show what that merger-level internalization looks like in practice -eight transactions where nothing changed except whose P&L received the commission.

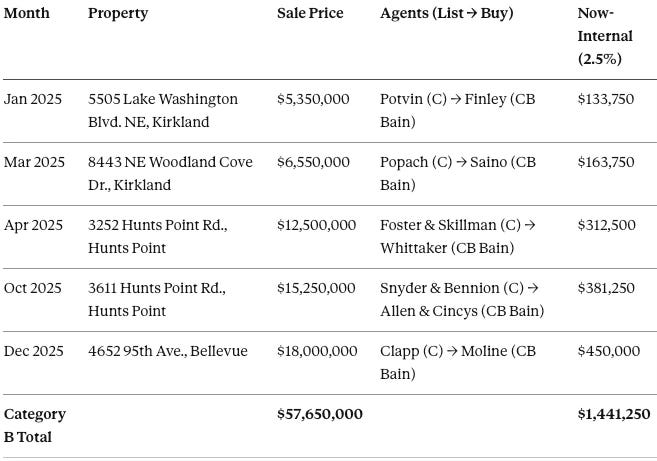

VII. Category B — Merger Internalization, Compass Listed / Anywhere Bought

Category B requires no private exclusive behavior to explain. These are ordinary cooperative transactions — a Compass listing agent, a CB Bain buyer agent, an MLS-exposed sale — that became internal revenue the moment the merger closed. The agents involved did nothing differently. Their clients experienced nothing differently. But the commission that previously crossed corporate lines now stays inside the combined entity. This is the merger as commission-transfer mechanism, operating invisibly at the transaction level.

Five transactions where Compass held the listing and a Coldwell Banker Bain agent brought the buyer. Before the acquisition, that buyer-side commission was competitive revenue leaving the firm. After the acquisition, it stays inside the combined entity. Nothing changed in the transaction. The merger changed the accounting.

CB Bain is the dominant Anywhere brand in Seattle’s Eastside luxury market —historically Compass’s primary competitor for buyer-side representation in the same geography. The merger did not create this buyer network. It acquired it, converting CB Bain’s competitive presence from a rival into a revenue line. The December 2025 Bellevue transaction at $18 million is the largest single Category B event: $450,000 in buyer-side commission that no longer crosses corporate lines. Hunts Point Road appears twice — $12.5 million in April and $15.25 million in October — same pattern both times.

$1.44 million in buyer-side commission internalized without a single agent changing behavior. That is the acquisition’s commission-transfer logic made concrete. Category C shows the same logic running in reverse.

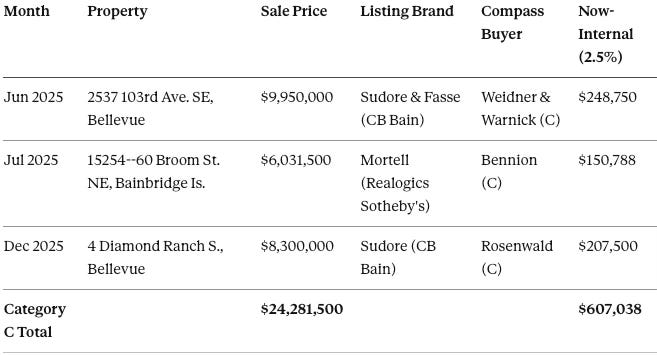

VIII. Category C — Merger Internalization, Anywhere Listed / Compass Bought

Category C confirms that the internalization logic runs in both directions. When an Anywhere brand holds the listing and a Compass agent represents the buyer, the commission flow that previously crossed corporate lines now stays inside the combined entity just as it does in Category B. The merger did not create a one-way valve. It created a closed loop — any transaction touching either brand on either side now contributes to the same balance sheet.

Three transactions where an Anywhere brand held the listing and a Compass agent represented the buyer. The same internalization logic runs in reverse.

Categories B and C together — eight transactions, $81.9 million, $2.0 million in buyer-side commission — require no private exclusive behavior to explain. They are the mechanical output of the merger itself. The acquisition was the commission-transfer mechanism. Private exclusives amplify the conversion rate. The two layers compound.

Together, Categories A, B, and C account for $4.2 million in internalized buyer-side commission from 16 transactions. Category D shows what happens to the remaining 12 Compass listings where the open market was allowed to function.

IX. Category D — What Transparency Preserves: The Conversion Frontier

Category D is not a competitive failure for Compass. It is the open-market outcome the private exclusive model is engineered to prevent — and the $2.4 million it represents is the most direct quantification of what sellers lost access to when the mechanism operated successfully in Categories A, B, and C. These are Compass listings that reached the open market — and as a result, an independent buyer's agent competed for and won the buyer-side commission. From a consumer protection standpoint, Category D is the success case: competition functioned, an outside agent served the buyer, and the seller’s listing received full market exposure. From Compass’s Layer 3 standpoint, each Category D transaction is $150,000 to $400,000 in buyer-side commission that left the network. The private exclusive model exists to convert these outcomes into Category A outcomes.

Twelve transactions where Compass held the listing and an independent buyer’s agent won the buyer-side commission. These are not competitive failures for Compass. They are the open-market outcomes the private exclusive model is designed to eliminate.

This is the $2.4 million that leaves the Compass network because these listings reached the open market. Every Category D outcome is a conversion failure from Compass’s Layer 3 perspective. The private exclusive model targets exactly this rate — routing internal buyers to Compass listings before the market sees them, converting Category D outcomes into Category A outcomes without gaining a single point of nominal market share. Concurrent marketing requirements make Category D permanent.

January 2026, 9001 NE 14th St., Clyde Hill: Foster and Skillman listed the $13.5 million property — the same Clyde Hill submarket where MLS #2478948 at 8631 NE 19th Place is currently active at $7,250,000, also Foster/Skillman listed, as of February 19, 2026. Anna Riley and Denise Niles of Windermere East brought the buyer. $337,500 in buyer-side commission left the Compass network because the listing reached the open market and an independent agent competed for it. Concurrent marketing requirements lock in that outcome. The private exclusive model exists to prevent it.

Windermere East alone appears seven times as the winning outside buyer brokerage across the twelve Category D transactions. The firm that could “clean house” with private exclusives — Lucy Wood’s own words under oath — wins open-market competition repeatedly when Compass listings reach full exposure. That is not coincidence. It is what a functioning market looks like.

X. The Arithmetic of Capture

The four categories collapse into a single table. What that table shows is not merely commission flows — it shows the gap between Compass’s current internalization rate and the rate the private exclusive model is engineered to reach. The arithmetic of that gap is the arithmetic of the Layer 3 premium.

The category table above breaks down the mechanism by transaction type. The summary table below collapses those categories into a single arithmetic: 16 transactions, $167.5 million in transaction value, $4.2 million in internalized buyer-side commission — from one market's top-10 record alone. The gap between the $4.2 million captured and the $2.4 million that left the network through Category D is the conversion frontier. Closing that gap is the entire purpose of the private exclusive program.

The $4.2 million in captured buyer-side commission is a floor, not a ceiling. It covers only the top-10 transactions per month in one market. But the more important number is the structural ratio inside the dataset itself.

Of the 130 transactions in the thirteen-month record, 16 — approximately 12.3% — produced commission flows that stayed or now stay entirely inside the combined Compass-Anywhere entity. That is the fully internalized share. But Compass appears on at least one side in 28 of the 130 transactions — 21.5% of the full top-10 luxury universe. The gap between 12.3% and 21.5% is the conversion frontier: transactions where Compass held the listing or represented the buyer but did not capture the other side. The private exclusive model closes that gap by routing internal buyers to Compass listings before the market sees them — converting Category D outcomes into Category A outcomes without gaining a single point of nominal market share.

Scaled to Compass’s 35 major markets at 10-15 times the top-10 transaction volume, the same internalization rate implies $600 million to $1.5 billion of the acquisition price resting on a single operating condition. Washington just eliminated that condition. Every state that follows eliminates it further. The forward version of this arithmetic is already visible: seven active Team Foster listings on fosterrealty.com as of February 19, 2026 — $136 million in inventory, $3.4 million in buyer-side commission at stake — with MLS #2392995, a $79,000,000 Lake Washington estate, listed without an address. When those transactions close, the MLS will record who represented the buyer. If the pattern documented in MLS #2362507 and MLS #2457071 repeats, the conversion frontier will have advanced by $3.4 million in a single inventory cycle, from a single team, in a single market, during the legislative session that was deciding whether to close it permanently.

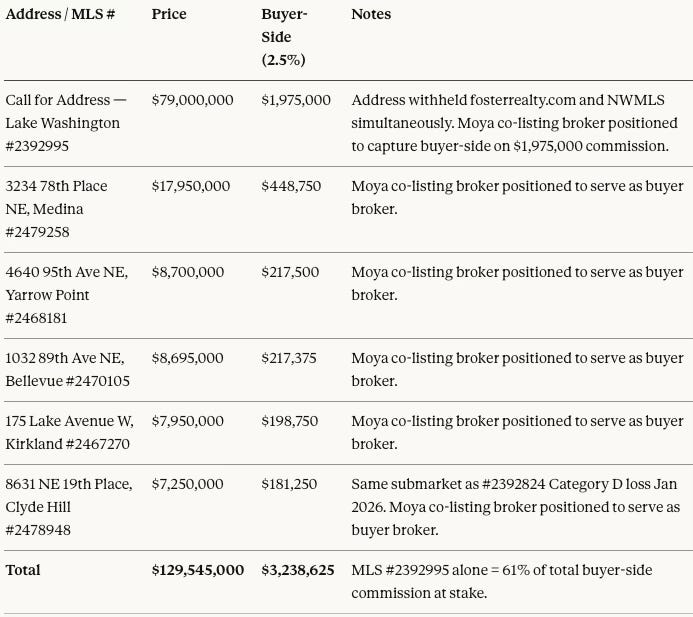

The seven active Team Foster listings documented on fosterrealty.com on February 19, 2026 are not static evidence. They are a prospective record. When each closes, the NWMLS will record the buyer broker’s name and brokerage. The methodology that produced the thirteen-month historical dataset applies directly: if the buyer broker on any of the seven transactions is a Compass or Anywhere agent, the transaction is Category A or merger-internalized. If the buyer broker is an independent agent, it is Category D. The MLS timestamps will show whether the buyer arrived before or after meaningful market exposure.

MLS #2392995 — the $79,000,000 Lake Washington estate currently listed without an address — is the highest-stakes prospective transaction in the dataset. At 2.5% buyer-side commission, $1,975,000 turns on who represents the buyer at closing. The address suppression documented on February 19, 2026 is the mechanism that narrows the buyer pool to those who contact Team Foster directly. The closing record will show whether that narrowing produced an internal buyer.

Any state AG, legislative staff member, or opposing counsel who bookmarks fosterrealty.com and checks the NWMLS closing records for these seven listings over the next six months will have a prospective confirmation or disconfirmation of the mechanism the historical dataset documented. The test is already running. The results are publicly available the moment each transaction closes.

Active Inventory Commission Exposure — Team Foster / Compass, February 19, 2026

MLS #2392995 alone represents 58% of total buyer-side commission at stake across all seven active listings. The prediction is simple and falsifiable. When each of the seven active listings closes, the NWMLS will record the buyer broker’s name and brokerage. If those transactions terminate inside the Compass–Anywhere network, the internalization model holds. If independent brokers win the buyer side at rates consistent with Category D, the model weakens. The closing records will resolve the claim without interpretation.

XI. Transparency Laws: The State-Level Enforcement Architecture

Every state that passes a no-opt-out concurrent marketing requirement closes another piece of the $400-800 million regulatory assumption embedded in the Anywhere acquisition premium — independently, without coordination, and without a single subpoena. The bill is not the only output a state produces when it holds transparency hearings. The testimony record is. Once a Compass representative testifies before a legislative committee — or declines to testify after signing in — that record enters a permanent, discoverable, cross-jurisdictional public archive. Every subsequent state that advances a transparency bill inherits Washington’s evidentiary foundation without having to generate it from scratch. The signal travels regardless of whether the statute passes. This section explains why the legislative architecture is more durable than it appears from any single jurisdiction’s outcome.

Every state considering a transparency bill faces the same design fork. The Washington record is the most complete evidentiary instance of how that fork plays out — but the structural logic is portable to any jurisdiction.

Wisconsin enacted Act 69 — the first state transparency mandate — in December 2025, effective January 2027. Illinois reintroduced its concurrent marketing bill in February 2026. Each state that acts creates a comparative baseline for the next. The transaction record — monthly, public, arithmetically legible in any market where Seattle Agent Magazine equivalents exist — travels with it.

The design choice that distinguishes Washington from Wisconsin is structural, not procedural. Wisconsin included an opt-out provision. Washington did not. That distinction matters because at platform scale, an opt-out is not consumer protection — it is an embedded default the dominant firm can pre-select in listing agreements and train 37,000 agents to frame as “premium service.” Compass’s twelve-word amendment request was precisely that mechanism. The Senate rejected it because it understood what it was. A transparency bill with a Compass-controlled opt-out is not a transparency bill. It is information-control infrastructure with a consent wrapper.

The enforcement architecture has a second structural feature that the bill-versus-signal distinction clarifies. A state does not need to pass a transparency law to generate enforcement-grade evidence. Legislative testimony is a one-way gate: once a firm’s representative testifies, the contradictions enter a permanent, discoverable, cross-jurisdictional public record. A failed bill that produces testimony documenting cross-forum inconsistency has already accomplished the enforcement-relevant work. Every state attorney general can access Washington’s hearing record. Every subsequent state that holds hearings widens the available record. The signal compounds; the statute is secondary.

Washington’s hearing record produced three specific documentary outputs that travel: Huff’s admission that business-model questions were above her authority, three committee members’ documented questioning of the cross-forum contradiction, and the AG’s Civil Rights Division appearing as “other” — supporting the policy goal while recommending a UDAP vehicle rather than the Washington Law Against Discrimination. The AG’s office independently confirmed that enforcement authority exists under UDAP for exactly the conduct the hearing documented. That record is now available to every state AG investigating the same business model.

The national architecture is straightforward. The Parker v. Brown state-action immunity doctrine — conventionally read as a defensive shield — functions as an offensive tool as multi-state adoption accelerates. The first state faces the strongest legal challenge from the firm seeking to preserve its business model. By the fifth state, the challenge is structurally untenable: each adopting state reinforces the “clearly articulated state policy” standard, making federal preemption arguments progressively weaker. California, New York, and Texas — the other major concentration markets post-merger — are the states where the Compass-Anywhere platform-wide architecture faces its most consequential exposure. If those states adopt Washington's no-opt-out model, the 3-Phase Private Exclusive strategy collapses at national scale — and the goodwill impairment question stops being theoretical. Five states with no-opt-out concurrent marketing requirements is not a regulatory headwind. It is a material assumption failure in the Anywhere acquisition underwriting.

The enforcement ratchet and the legislative ratchet run on the same track. Each state that testifies, each AG that opens an investigation, each court that cites a prior ruling narrows the space in which the Layer 3 mechanism can operate. Washington proved the mechanism cannot withstand simultaneous legal, legislative, and transactional visibility. The question for every other state is only how fast the same visibility arrives.

XII. The One Downside Reffkin Didn’t Count

Compass’s public defense of private exclusives rests on a single empirical claim: that sellers face no financial downside from withholding their listing from the open market. Robert Reffkin made this claim publicly, on the record, in an earnings call. Compass’s own client-facing disclosure form contradicts it directly. That gap —between the CEO’s public statement and the company’s own written disclosure — is not ambiguity. It is the deceptive trade practices exposure documented in Section II, expressed in the plainest possible terms. It also happens to be the claim that collapsed most visibly in Washington’s hearing rooms.

On Compass’s Q1 2025 earnings call, Robert Reffkin answered his own question about private exclusives: “There is no downside. The worst thing that happens is a homeowner gets an offer, and they have an opportunity to turn it down and go to the public sites with the benefit of price discovery from pre-marketing. That’s the downside, which means there is no downside” (www.housingwire.com).

Reffkin was describing financial downside. He didn’t account for the other kind.

The NWMLS record for MLS #2362507 at 1628 72nd Ave. SE, Mercer Island is the other kind made concrete. Tere Foster and Moya Skillman represented the seller. Tere Foster and Moya Skillman represented the buyer. On a $15,000,000 transaction, the agents whose compensation depended on the deal closing were simultaneously advising the seller on whether to accept the offer and advising the buyer on what to offer. Compass's own Disclosure Form acknowledges that private exclusive marketing may reduce the number of offers and the final sale price. The NWMLS record shows the agents who made that tradeoff on the seller's behalf were the same agents collecting the buyer-side commission when it resolved.

Luxury real estate is a high-trust industry in a specific structural sense: the transactions are too large, too infrequent, and too information-asymmetric for buyers and sellers to independently verify what they’re getting. A $15 million Mercer Island estate is not a commodity purchase with a published price history and competitive bids visible in real time. The seller depends almost entirely on the agent’s representation of how the market was exposed, who saw it, and whether the offer received reflects what full competition would have produced. That dependency is the foundation of the fiduciary relationship — and the private exclusive model structurally compromises it, because the agent holding the listing has a direct financial incentive to route the transaction internally before full market exposure occurs.

Compass told the Washington legislature the opposite. Before the Senate committee, the argument was seller privacy and autonomy. Before the federal court, the same information restriction was a competitive right. In investor communications, it was a revenue strategy. Compass’s own Disclosure Form acknowledged the mechanism plainly — private exclusive marketing “may reduce the number of potential buyers,” “may reduce the number of offers,” and may reduce “the final sale price” — but that document does not appear in legislative testimony.

The hearing record shows what forum fragmentation looks like when the forums converge. Compass’s regional vice president, the company’s named spokesperson on private exclusives in every trade publication, signed into both hearings without disclosing her affiliation and said nothing. The managing director sent in her place couldn’t answer whether the private exclusive model affects Compass’s business. Brokers who registered to testify didn’t appear when questioning intensified. Reffkin’s “no downside” is a public record. The Disclosure Form’s acknowledgment of price suppression risk is a public record. The gap between the two entered the permanent legislative transcript — in a state whose committee members asked the exact questions Compass declined to answer.

The “no downside” claim is now competing with the Disclosure Form in the same publicly accessible legislative record. Any seller, regulator, or opposing counsel who pulls the Washington hearing transcript can read both. Reffkin’s statement did not survive the public record. The Disclosure Form already conceded the argument he was making.

XIII. The Windermere Contrast

The necessity argument — that private exclusives are a competitive requirement for any brokerage that wants to serve luxury sellers — collapses under a single data point. Windermere East holds approximately 35% of the Seattle luxury market by transaction count, appears seven times in the Category D table as the outside brokerage that won buyer-side commission on Compass listings, and its Regional Director testified under oath that Windermere could run the private exclusive playbook and chose not to. The January 2026 Clyde Hill sale at $13.5 million — the dataset's highest-value Category D transaction — went to Windermere. That testimony now sits in the same public record as Compass's cross-forum contradictions. The dominant firm in the market explicitly rejected the practice Compass calls a competitive necessity. The argument does not survive that comparison.

Lucy Wood, Windermere’s Regional Director, testified at both the Senate and House hearings on Washington’s concurrent marketing bill. She stated directly that Windermere could “clean house” with private exclusives given its market position —and that Windermere chose not to. Not competitive disadvantage accepted reluctantly. A stated business model choice, delivered under oath, in the legislative record of the committee voting on the bill. For the full comparison of these two market philosophies, see Windermere and Compass, Two Philosophies of Real Estate.

In a trust-dependent industry, institutional credibility is balance-sheet-adjacent. Windermere’s Lucy Wood told the same committee Windermere could profit from private exclusives and voluntarily declines. That statement, delivered under oath, is now a permanent record. Any seller choosing between Compass and Windermere in the Seattle market has access to both. The “no downside” claim does not survive that comparison.

The silence from every other brokerage in the market is the structural complement to Windermere’s testimony. Seattle’s luxury market is relationship-dense and referral-dependent. A broker who publicly names the Foster-Skillman pattern risks losing referral flow from Team Foster, being frozen out of co-listing opportunities on Foster inventory, and signaling to every top producer in the market that they are willing to create friction in an environment where today’s competitor is tomorrow’s co-broker on a $15 million sale. The silence is not ignorance. It is rational self-interest operating exactly as the market structure predicts.

The local industry dynamics is why third-party documentation matters more than industry self-policing. The Washington DOL does not need a competing broker to file a complaint. The AG’s office does not need an industry witness. The transaction record is public, the MLS role designations are public, and the pattern is documented across 130 transactions without a single industry source required. MindCast’s analytical independence is structurally significant — no referral relationships, no co-brokerage exposure, no reason to stay quiet. The analysis stands on public records alone. That is what makes it actionable by regulators in a way that competitor testimony never would be.

XIV. The Legislative Pattern: What Compass Does and Why It Fails

The intensity of Compass's legislative opposition — federal litigation, coordinated hearing appearances, the twelve-word amendment — is only legible against the Layer 3 premium it was defending. A firm fighting a transparency bill on seller-choice grounds does not deploy a regional vice president in trade media across every jurisdiction simultaneously. A firm defending $400-800 million of acquisition value does.

Understanding why Compass’s legislative strategy failed in Washington requires understanding the strategy itself. Compass did not send its most capable spokesperson. It did not answer the cross-forum contradiction. It did not let its own managing brokers testify when questioning intensified. These are not tactical errors. They are the deliberate outputs of a forum fragmentation strategy — the same strategy that works when legal, legislative, and investor audiences remain separated. Washington collapsed that separation. The record that resulted is now available to every jurisdiction that follows.

Compass’s legislative opposition follows a documented pattern across every jurisdiction that advances a transparency bill. Washington produced the most complete evidentiary record of that pattern because both Senate and House hearings occurred in compressed sequence, forcing simultaneous visibility. The pattern holds regardless of state.

Compass’s Pacific Northwest spokesperson is Cris Nelson, Regional Vice President. When NWMLS suspended Compass’s IDX feed in April 2025, Nelson was the named Compass voice in every major trade outlet. She told Inman: “NWMLS is a broker-owned MLS and is the only MLS in the country that prohibits agents from marketing a property on the internet — privately or publicly — unless it’s listed in the MLS.” She told RISMedia that NWMLS’s enforcement was “a stark example of monopolistic control” that “limits homeowner choice, stifles competition and sets a dangerous precedent.” She gave the same defense to Real Estate News and HousingWire. The Compass press release announcing its lawsuit against NWMLS quoted Nelson by name and title defending the 3-Phase Private Exclusive program: “When given the choice, 36% of homeowners working with a Compass agent in Seattle chose to pre-market their home as a Compass Private Exclusive.” She is the company's designated public voice on exactly the question the transparency bill addressed — and the company's designated silence in the only forums where that voice could be cross-examined.