MCAI Lex Vision: How the Compass–Anywhere Merger Reshapes Broker Bargaining Power

Architectural Monopsony and Lemley's Labor-Antitrust Framework

Companion study to MCAI Lex Vision: Compass–Anywhere, When Scale Becomes Liability, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics, Anchored in Coordination-Cost Economics (Jan 2026) (Part I), Compass’s Technology Trap, How IPO Narrative Became Its Antitrust Liability (Jan 2026) (Part III), Washington’s SB 6091 and Private Real Estate Market Control (Jan 2026) (Part IV). See also See also How Trump Administration Political Access Displaced Antitrust Enforcement—and Why States Should Now Step In (Jan 2026).

Executive Summary

Stanford law and economics professor Mark Lemley’s recent working paper, The Implications of Labor Antitrust for Merger Enforcement (available on SSRN), changes how Section 7 of the Clayton Act applies to mergers affecting labor markets. Lemley establishes three propositions that reshape merger doctrine: (1) Section 7’s incipiency standard applies to labor-market harm, authorizing intervention before monopsony power hardens; (2) barriers to exit—not firm counts—determine labor-market power; and (3) labor-cost reductions achieved through monopsony are transfers, not efficiencies, and cannot be offset by consumer-side benefits under Philadelphia National Bank. These propositions convert architectural control over contractor infrastructure into cognizable merger harm.

Lemley's framework is recent scholarship, not settled doctrine, and represents one intervention in an ongoing debate about labor-market effects in merger review. The analysis here applies his framework to test its explanatory power, not to foreclose alternative approaches.

Application to Compass–Anywhere. The Lemley framework fits Compass–Anywhere precisely. The merger consolidates control over MLS coordination, listing visibility, lead routing, and workflow infrastructure—the mechanisms that determine how broker-contractors earn income and switch platforms. Under Lemley’s analysis, these architectural choices function as exit barriers equivalent to noncompetes, stay-or-pay clauses, and nonsolicitation agreements. The merger can violate Section 7 even if commission rates and housing prices remain unchanged.

Extension to Broker-Contractors. Lemley’s paper focuses primarily on traditional employees and, to a lesser extent, on gig workers and content creators. Broker-contractors occupy an intermediate category: formally independent, licensed professionals who nonetheless depend on platform infrastructure for market access. The extension is justified by the same economic logic Lemley applies: where earnings depend on access to coordination infrastructure controlled by a concentrated buyer, the buyer exercises labor-market power regardless of the formal employment relationship.

How This Publication Differs. MindCast AI foresight simulations typically run multi-actor Cognitive Digital Twin (CDT) foresight simulations with probability-weighted scenarios and enforcement-timeline predictions. The present study does not run a foresight simulation. Instead, it performs doctrinal translation: applying Lemley’s labor-antitrust framework to coordination-architecture mechanisms in residential brokerage. The outputs are testable indicators—Lemley-derived, falsifiable hypotheses—rather than probabilistic forecasts. A full Lemley Labor-Merger Monopsony (LLMM) CDT foresight simulation will activate when Phase 2 execution signals (split compression, routing stratification, Small but Significant and Non-transitory Decrease in Wages (SSNDW) evidence) become observable.

Roadmap. Section I explains what Lemley changes about merger review: incipiency, consumer-welfare correction, exit barriers, and platform-mediated labor. Section II defines the relevant labor market and applies the SSNDW test. Section III analyzes Compass–Anywhere as a labor-side merger. Section IV examines post-merger conduct as evidence of exit-barrier design. Section V maps MCAI coordination metrics to Lemley’s framework. Section VI addresses clearance risk and under-enforcement. Section VII proposes Lemley-consistent remedies. Section VIII specifies testable indicators. Section IX provides an enforcement outlook Section X acknowledges limitations.

Contact mcai@mindcast-ai.com to partner with us on Law and Behavioral Economics foresight simulations. See recent publications:

MCAI Economics Vision: Chicago School Accelerated — The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics, Why Coase, Becker, and Posner Form a Single Analytical System (Dec 2025)

MCAI Innovation Vision: The Federal-State AI Infrastructure Collision, When Federalization Meets Federalism (Jan 2026)

MCAI Lex Vision: Private Equity, NIL, Antitrust, and the Firm-Formation Phase of College Athletics, Capital Reorganization Under Regulatory Stasis (Jan 2026)

MCAI Lex Vision: From Open Market to Private Governance, Coordination Capture in the Compass–Anywhere Merger, Comment on Senators Warren-Wyden Letter to US DOJ and FTC (Dec 2025)

I. What Lemley Changes About Merger Review

Lemley’s labor-antitrust merger framework repairs core weaknesses in modern antitrust merger doctrine. His intervention returns Section 7 to its statutory design and clarifies how mergers can be anticompetitive even when consumer prices remain stable.

A. Restoring Section 7’s Incipiency Standard

Section 7 prohibits mergers whose effects “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” As Brown Shoe held, the statute’s purpose is to block mergers “when the trend to a lessening of competition... was still in its incipiency.”

Labor markets are where incipient harm appears first. Switching jobs is costly. Bargaining power erodes gradually as alternatives narrow. Exit constraints bind long before downstream prices move. Waiting for consumer effects misapplies Section 7 and arrives after exit barriers harden.

Applied to Compass–Anywhere, the merger alters labor-market structure immediately—by reshaping how agents access demand and income—even if consumer-facing effects would lag by months or years. Section 7’s incipiency logic authorizes intervention now, based on structural change, not later, based on realized consumer harm.

B. Correcting the Consumer-Welfare Narrowing

Beginning in the 1980s, merger enforcement collapsed into a consumer-price test, allowing mergers that depress wages to pass review so long as consumer prices do not rise. Lemley’s correction rests on two points—one economic, one legal.

The economic point: A monopsonist does not simply pay less while maintaining output. It reduces the quantity of labor demanded in order to suppress wages. As Lemley explains, “a firm with monopsony power will act as if its marginal costs are higher, not lower, in the downstream market.” The result is reduced output—fewer transactions supported, fewer agents fully utilized—even as the firm captures supracompetitive returns. Labor-cost reductions achieved through monopsony are transfers, not efficiencies.

The legal point: Merger law does not treat consumer-side benefits as a license to impose anticompetitive harm in a distinct labor market. Section 7 can condemn a merger based on labor-market harm without netting it against claimed consumer gains. Even if Compass–Anywhere could prove that platform consolidation benefits homebuyers, consumer benefits do not offset the harm to the approximately 340,000 agents (per deal reporting) whose bargaining power is suppressed.

The implication for Compass–Anywhere: the merger can violate Section 7 even if commission rates, transaction fees, or housing prices remain unchanged.

C. Substituting Exit Barriers for Formal Concentration

Beyond correcting the consumer-welfare narrowing, Lemley replaces traditional concentration metrics with exit-barrier analysis. Traditional merger analysis emphasizes market share and firm count; Lemley shows why that lens fails in labor markets: what determines power is not how many employers exist on paper, but how costly it is to leave.

Switching jobs is “a very big deal”: it entails interview rounds, reputational signaling risks, income discontinuity, and often geographic and family costs. Even modest increases in exit cost can materially suppress bargaining power long before wages visibly change.

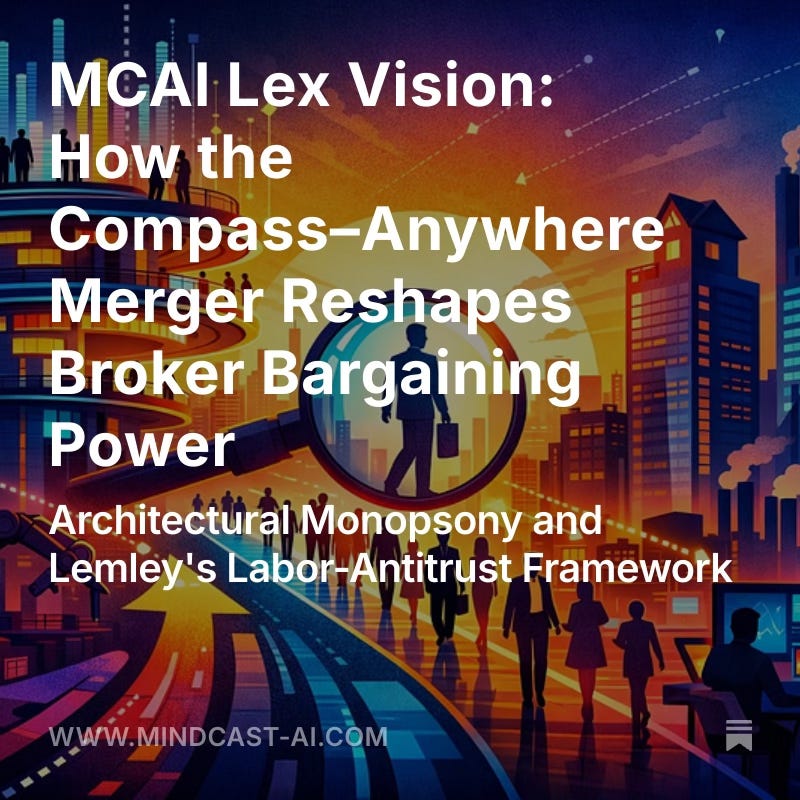

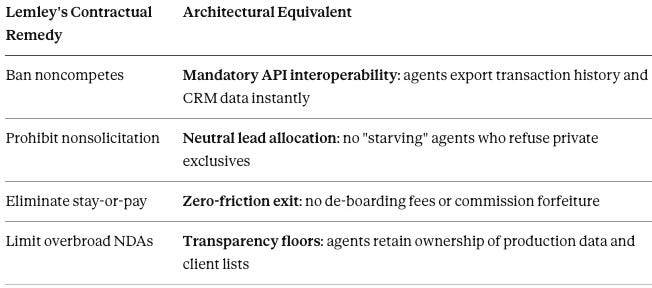

Lemley catalogs the contractual mechanisms firms use to raise exit barriers: noncompete agreements (affecting over 20% of the workforce), nonsolicitation agreements, stay-or-pay clauses, overbroad NDAs, and no-poach agreements. For Compass–Anywhere, the barriers operate through architecture rather than contract:

Raising the cost of switching reduces the competitive constraint that outside options impose. MLS completeness, listing visibility, lead routing, and workflow portability therefore function as exit conditions, not neutral business features.

D. Platform-Mediated Labor and Architectural Power

Exit-barrier analysis gains particular force in platform-mediated labor markets. Lemley’s framework suits markets where labor is formally independent but economically dependent. Content creators and gig workers “face concentrated buyers for their services” even though they are not employees.

Broker-contractors fit the same pattern. Residential real estate agents are licensed professionals who operate as independent contractors, but their earnings depend on infrastructure they do not control: MLS access, listing visibility, consumer portals, lead generation, and transaction tools. When a merger consolidates control over that infrastructure, the merged firm exercises labor-market power through design choices rather than wage setting.

Lemley’s framework captures this: “Just as a monopoly can reduce output and raise prices for consumers, a monopsony can reduce demand for labor and lower wages below the market-clearing price.” In platform-mediated markets, “reducing demand for labor” manifests as reducing effective access to transactions—through listing de-prioritization, lead routing away from disfavored agents, or information asymmetries that advantage network insiders.

II. Defining the Relevant Labor Market in Residential Brokerage

With Lemley’s doctrinal framework established, the next step is market definition. Applying Lemley’s framework requires defining broker-contractors as labor-market participants and specifying the market boundaries. The SSNDW test provides the analytical tool.

A. Why Broker-Contractors Are Labor Market Participants

Broker-contractors are not employees, but Lemley’s framework applies to “independent contractors who face concentrated buyers for their services.” The relevant criterion is economic dependency, not formal employment status.

Precedent supports this extension. In NCAA v. Alston, the Supreme Court treated student athletes as labor-market participants for antitrust purposes, referring to the case as “involving monopsony in the labor market” even though the athletes were formally students. Broker-contractors share the economically relevant characteristics: formal independence combined with economic dependency on brokerage-controlled infrastructure, concentrated buyers after the merger, and high switching costs.

B. What Constitutes the “Market”: The SSNDW Test

The SSNDW (Small but Significant and Non-transitory Decrease in Wages) is the labor-market equivalent of the SSNIP test. The question: can the merged firm decrease compensation by 5% without losing workers?

Applied to Compass–Anywhere: Could the merged firm decrease effective agent compensation—through lower splits, reduced lead quality, or degraded support—by 5% without significant agent exit? Given the architectural lock-in identified throughout this analysis, the merger plausibly increases the firm’s capacity to execute an SSNDW. Section VIII specifies indicators that will test whether that capacity is in fact exercised without exit.

The SSNDW framework also captures subtler mechanisms that reduce compensation without changing nominal splits:

Lead quality degradation: Routing higher-value inquiries to preferred agents

Support tier differentiation: Reducing services for agents outside favored categories

Visibility throttling: De-prioritizing listings from non-compliant agents

All three mechanisms become feasible when exit barriers prevent agents from responding by leaving.

C. MLS as Coordination Infrastructure for the Labor Market

Market definition also requires attention to coordination infrastructure. MLS functions as coordination infrastructure; from a labor-antitrust perspective, MLS enables competitive labor markets for agents.

When MLS operates as intended—with mandatory, timely submission and equal data access—agents can switch brokerages without losing access to market information or visibility. When MLS completeness erodes, agents become more dependent on their current brokerage’s proprietary infrastructure, and exit costs rise. MLS completeness is therefore not merely a consumer-protection issue but a labor-market-structure issue.

III. Compass–Anywhere as a Labor-Side Merger

Having defined the labor market and its coordination infrastructure, the analysis turns to the merger itself. The merger consolidates control over the infrastructure that determines agent earnings and mobility. Evaluated under Lemley’s framework, Compass–Anywhere strengthens monopsony power through architectural control rather than wage suppression.

A. What the Merger Consolidates

The combined entity controls four critical infrastructure layers:

Listing infrastructure: The largest inventory of residential listings, with power over initial visibility through private exclusive programs, MLS submission timing, and syndication.

Consumer-facing demand: Through brokerage-owned websites and apps, the firm controls significant consumer traffic and lead routing.

Agent operating systems: The unified Agent Operating System serves approximately 340,000 agents (per deal reporting), creating dependency on proprietary CRM, marketing, and transaction tools.

Brand portfolio: Compass combined with Anywhere’s brands (Coldwell Banker, Century 21, Sotheby’s, Corcoran, Better Homes and Gardens Real Estate) covers luxury to mass-market segments.

B. Monopsony Through Architecture

Traditional monopsony operates through wage suppression; Compass–Anywhere’s monopsony operates through architectural control that reduces effective outside options.

The merged firm does not need to reduce commission splits to exercise monopsony power. It can:

Route leads preferentially to favored agents

Determine listing visibility through private exclusives or delayed MLS submission

Create information asymmetries advantaging network insiders

Raise switching costs through non-portable data and workflows

Technology as Legal Exposure. Under Lemley's framework, Compass's technology investments create legal risk, not just competitive advantage. Every platform feature that raises switching costs—non-portable data, proprietary workflows, integrated CRM, platform-mediated client relationships—functions as an exit barrier. The Agent Operating System is not merely infrastructure; it is the mechanism through which monopsony power operates. The more successful the platform at retaining agents through integration, the stronger the Section 7 case becomes.

Architectural choices of this kind affect earnings without touching nominal splits—the platform-mediated equivalent of wage suppression.

C. The “Your Listing, Your Lead” Framework

Post-merger communications from Compass leadership emphasized “your listing, your lead”: agents who list properties receive preferential routing of buyer inquiries. Under Lemley’s framework, this reveals the monopsony mechanism:

Consumer inquiries route through brokerage-controlled systems

The brokerage determines the relationship between listings and leads

Agents outside the network face disadvantages in lead access

IV. Post-Merger Conduct as Evidence of Exit-Barrier Design

The merger’s structural features, examined in Section III, create monopsony capacity. Post-merger conduct provides evidence of how that capacity translates into exit-barrier design. Lemley emphasizes that barriers to exit need not be formal to be effective. His analysis of unenforceable noncompetes is instructive: even illegal contracts deter job changes because employees “may not know they are illegal or may not have the time and money to challenge them.”

Informal Architecture: Private Exclusives, Lead Routing, Non-Portable Data

The same principle applies to Compass–Anywhere’s “voluntary” architecture. Private exclusives are formally optional, but formal voluntariness becomes behavioral coercion when:

Platform defaults favor private channels: If the interface makes private-first listing the easiest option, agents follow the path of least resistance.

Lead routing creates incentives: If private-exclusive participation yields preferential leads, the “voluntary” choice becomes economically compelled.

Exit means losing accumulated value: If transaction history and client relationships are locked in non-portable systems, switching costs are substantial.

Alternatives degrade: If MLS completeness declines because the dominant firm routes through private channels, non-network affiliation becomes less attractive.

Lemley’s framework recharacterizes these as functional barriers to exit—the architectural equivalent of contractual restraints. But Compass does not rely on architectural barriers alone.

Formal Architecture: Contractual Exit Barriers, Clawback Provisions

Compass’s exit barriers are not purely architectural. The company has used explicit contractual clawback provisions that function as stay-or-pay clauses—the mechanism Lemley identifies as a direct barrier to exit.

Typical Compass clawback terms include:

Sign-on bonus repayment: Agents who leave within 24-36 months must repay recruiting bonuses, often exceeding $100,000 for top producers

Marketing cost recovery: Departure triggers recapture of platform marketing expenditures attributed to the agent

Equity forfeiture: Stock grants vest over multi-year periods; early departure means forfeiture

Commission advance clawback: Advances against future commissions become immediately due upon exit

Under Lemley’s framework, clawback provisions are not merely compensation structure—they are exit penalties that suppress mobility and bargaining power. Unlike architectural barriers, clawbacks are written, quantifiable, and unambiguous. They document Compass’s intent to raise exit costs in terms Lemley’s framework makes directly actionable.

Post-merger, clawback exposure extends to Anywhere’s 340,000 agents. The question is whether legacy Anywhere agents will face Compass-style retention provisions—and whether existing provisions will intensify as the merged firm exercises consolidated labor-market power.

V. Mapping MindCast AI Metrics to Lemley’s Labor Framework

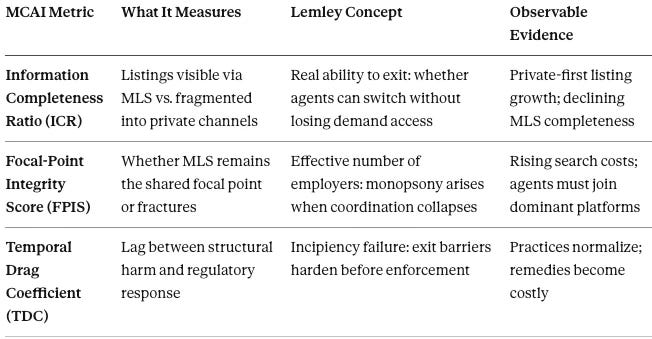

Sections I through IV establish Lemley’s doctrinal framework and apply it to the Compass–Anywhere merger. Operationalizing the framework requires translation into measurable indicators. Lemley’s concepts require translation into observable, falsifiable indicators. The metrics below define when a full LLMM CDT foresight simulation becomes analytically valid.

A. Exit Barriers: From Theory to Measurement

Three MCAI metrics operationalize Lemley’s exit-barrier framework:

In the Compass–Anywhere context, the Agent Operating System, proprietary CRM histories, listing-performance data, and internal lead-routing logic function as high-friction lock-in mechanisms—structural exit barriers, not neutral business features.

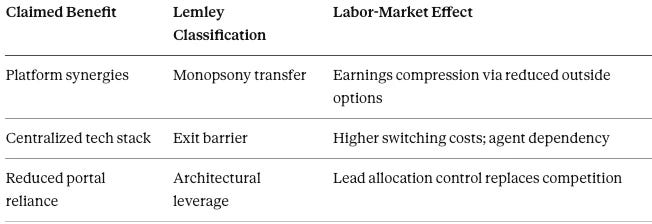

B. Efficiencies vs. Labor Suppression

Lemley’s core critique: “Labor savings aren’t efficiencies, they are inefficiencies.”

The Philadelphia National Bank Shield: Even if consumer benefits exist, they cannot legally offset labor harm. The efficiency defense fails on both economic grounds (transfers ≠ efficiencies) and legal grounds (out-of-market benefits cannot justify in-market harm).

VI. Clearance Risk and Lemley’s Under-Enforcement Critique

The metrics in Section V define how to measure labor-market harm; Section VI addresses why such harm went unexamined during merger review. Lemley observes that until very recently, the government “never... even evaluated a merger based on its labor market effects.” Labor harm is harder to measure than consumer-price effects, biasing enforcement toward consumer-side cases.

Reporting on the Compass–Anywhere review indicates that DOJ staff raised concerns warranting deeper investigation, but senior leadership allowed the merger to proceed without a Second Request. The pattern illustrates the incipiency failure Lemley warns against: by closing without investigation, leadership waited for realized harm rather than stopping the incipient trend.

VII. Lemley-Consistent Remedies

Under-enforcement does not foreclose future action. If enforcement proceeds post-close, Lemley’s framework shapes the remedy analysis. Lemley is skeptical of behavioral remedies: they are “rarely enforced and have proven ineffective.” The preferred response is structural: blocking mergers at the incipiency stage. Where agencies permit a merger despite labor concerns, remedies must be structural or self-executing:

Additional structural remedies:

MLS completeness floors: All listings submitted within 24 hours of marketing

Lead routing transparency: Disclosure of allocation algorithms

Consumer portal neutrality: No preferential treatment of network agents

The principle: remedies should change market structure, not rely on ongoing good behavior. As Lemley puts it: “Reduce exit costs; exit is the wage negotiation.”

VIII. Testable Indicators Under Lemley’s Labor-Merger Framework

Sections I through VII establish doctrine, apply it to Compass–Anywhere, and identify remedy options. Section VIII translates the framework into testable indicators that can validate or falsify the labor-monopsony thesis.

Methodological note. The indicators below are not outputs of a foresight simulation. Rather, they are Lemley-derived, falsifiable hypotheses that translate specific monopsony mechanisms into observable outcomes. Under Section 7’s incipiency standard, the relevant question is whether the merger has created the capacity to impose harm without exit—not whether that harm has hardened into equilibrium.

Each indicator has a specific threshold, timeframe, data source, and falsification condition.

A. Agent Mobility Decline

Indicator: Agent inter-brokerage movement rate declines by >15% within 18 months post-close for Compass–Anywhere agents, relative to pre-merger baseline.

Rationale: If the merger raises exit barriers, agents switch less frequently even with nominal alternatives.

Data sources: State licensing records (license transfers between brokerages); industry surveys (T3 Sixty, RealTrends).

Falsification: Mobility remains stable or increases.

B. Tenure-Split Correlation Weakening

Indicator: Correlation between agent productivity (GCI) and commission split weakens by >20% within 18 months for Compass–Anywhere agents relative to independent brokerage benchmarks.

Rationale: In competitive markets, top performers command top splits. In monopsony, the firm can “tax” high performers because they cannot credibly exit without losing infrastructure access.

Data sources: Agent compensation surveys; brokerage disclosure filings; whistleblower/discovery materials.

Falsification: High performers continue commanding proportionally higher splits consistent with pre-merger patterns.

C. Lead Allocation Stratification

Indicator: Within 12 months, evidence surfaces (discovery, whistleblower, regulatory inquiry) that Compass–Anywhere routes higher-value leads to agents who participate in private exclusives or use integrated services.

Rationale: Architectural wage suppression operates by reducing effective compensation through routing rather than split adjustment.

Data sources: Regulatory CIDs; class action discovery; agent surveys reporting differential lead quality.

Falsification: Lead routing is demonstrably neutral across compliance categories.

D. Private Listing Growth

Indicator: Private-first listings exceed 20% of new inventory in markets where Compass–Anywhere holds >30% share, within 12 months.

Rationale: Control over listing visibility is a primary monopsony mechanism.

Data sources: MLS data (submission timing vs. marketing activity); industry tracking (Altos Research, Redfin data center).

Falsification: Private-first rates remain below 20%.

E. Information Asymmetry Gap

Indicator: Non-network agents experience >20% increase in average Days-on-Market relative to network agents in same submarkets, within 12 months.

Rationale: If the platform de-prioritizes non-network listings, those agents become less competitive—equivalent to a wage cut achieved through visibility control.

Data sources: MLS DOM comparisons controlling for property characteristics; brokerage-level performance data.

Falsification: DOM remains comparable across network and non-network agents.

F. Golden Handcuffs Emergence

Indicator: Within 18 months, Compass–Anywhere introduces compensation structures functioning as stay-or-pay equivalents: deferred bonuses, equity vesting tied to tenure, or commission holdbacks released only upon renewal.

Rationale: Lemley identifies stay-or-pay as an explicit exit barrier. Platform-mediated equivalents make leaving economically punitive without formal contract terms.

Data sources: Agent compensation agreement changes; industry reporting; agent surveys.

Falsification: Compensation structures remain exit-neutral.

G. Discovery of Compensation Directives

Indicator: Within 24 months, regulatory inquiry or litigation discovery surfaces internal communications directing management to link compensation to private exclusive participation or design features increasing switching costs.

Rationale: Lemley emphasizes that monopsony intent is often documented internally. Discovery or whistleblower disclosure would test whether such evidence exists.

Data sources: CID productions; class action discovery; whistleblower disclosures.

Falsification: No such documents found.

IX. Enforcement Outlook

Based on the indicators in Section VIII, enforcement attention is more likely to emerge from state attorneys general or private class actions than from federal agencies. DOJ’s decision to allow the merger without a Second Request signals institutional reluctance to pioneer labor-market theories in merger review. State enforcers face lower barriers: UDAP statutes (California’s UCL, Washington’s CPA) do not require complex market definition, and fiduciary breach claims can proceed without proving antitrust injury.

The evidentiary record Compass created through pre-merger litigation strengthens plaintiff prospects. Pleadings in the NWMLS and Zillow cases document Compass’s strategic intent regarding MLS rules, Private Exclusives, and listing visibility—evidence that would otherwise require discovery. Post-merger, those documents become exhibits in conduct cases brought by competitors, agents, or regulators.

The fastest-moving vector is likely class action litigation. The Sitzer/Burnett plaintiffs’ bar has demonstrated capacity to reshape industry practices through private enforcement. Private Exclusive practices present a natural successor theory: sellers promised “maximum exposure” received systematic withholding designed to increase double-end probability. Agent-side claims—monopsony, fiduciary breach, deceptive compensation practices—may layer onto seller-side theories as the evidentiary record develops.

Timeline expectations: class action filing within 18 months; state AG inquiry within 24 months; federal action, if any, within 36 months and likely following rather than leading state enforcement.

X. Limitations

The analysis rests on an extension of Lemley’s framework to a novel context. Four limitations counsel epistemic humility without undermining the core analysis.

Novel extension: Lemley focuses on employees and gig workers. Extending his framework to platform-mediated professional contractors is justified by economic logic but untested in litigation.

Visibility of architectural barriers: Contractual barriers are written and challengeable. Architectural barriers operate through design and may be difficult to identify or measure.

Counterfactual uncertainty: Post-merger changes may reflect background trends (NAR settlement effects, macroeconomic conditions) rather than merger-specific harm.

Remedy feasibility: Proposed architectural remedies are theoretically coherent but practically untested.

Conclusion

The Compass–Anywhere merger illustrates the failure mode Lemley identifies in modern merger enforcement. By focusing on downstream prices and formal firm counts, regulators overlook how mergers reshape labor markets through architecture rather than wages.

Compass–Anywhere consolidates control over mechanisms governing agent visibility, lead flow, and workflow portability. Consolidation of this kind raises exit costs, suppresses bargaining power, and converts purported efficiencies into labor-market transfers. As Lemley puts it, “labor savings aren’t efficiencies, they are inefficiencies.”

Under Lemley’s framework, labor-market effects are not peripheral—they are the harm Section 7 was designed to prevent while still incipient. The coordination-architecture analysis identifies the mechanisms. Lemley establishes that labor-market effects are cognizable. Together, mechanism and doctrine show why Compass–Anywhere should be understood—and evaluated—as a labor-antitrust merger.

Appendix: Annotated Sources

A. Doctrinal Foundation

Mark A. Lemley, The Implications of Labor Antitrust for Merger Enforcement – Establishes Section 7 reaches mergers strengthening monopsony power, raising exit barriers, or suppressing labor earnings absent consumer price effects. Key passages: incipiency (pp. 5, 29); exit barriers (pp. 17–21); efficiency critique (pp. 26–29); remedies (pp. 30–33). Available at SSRN.

B. DOJ Review and Process Evidence

Provides the procedural record showing abbreviated review and internal disagreement at DOJ, which the draft uses as case-specific evidence of Lemley’s under-enforcement critique and the incipiency failure in clearing Compass–Anywhere without a full labor-side investigation.

Real Estate News, “How did the Compass–Anywhere deal get cleared so quickly?” – Documents abbreviated review and staff concern.

Bloomberg Law, “DOJ Allows Compass–Anywhere Deal Over Staff Antitrust Concerns” – Corroborates internal disagreement.

Wall Street Journal, “Real Estate Brokerages Avoided Merger Investigation After DOJ Rift” – Leadership-level intervention reporting.

HousingWire, “Compass–Anywhere merger DOJ review” – Industry understanding of clearance outcome.

C. Post-Merger Conduct Evidence

Documents deal closing, scale, and “your listing, your lead”/AOS messaging, supplying the factual basis for the draft’s characterization of CompassAnywhere’s architecture, agent lock-in, and monopsony mechanism (agent count, private exclusives, lead routing) rather than abstract hypotheticals.

Real Estate News, “What Reffkin told agents after Compass–Anywhere deal closed” – “Your listing, your lead” and AOS statements.

Real Estate News, “Compass completes its acquisition of Anywhere Real Estate” – Deal completion and market positioning.

The Real Deal, “Compass-Anywhere merger has closed: here’s what to know” – Deal terms and industry concerns.

HousingWire, “Compass closes $1.6B Anywhere merger, forms industry giant” – Scale claims (source for 340,000 agent figure).

Inman, “The deal is done: Compass and Anywhere have officially merged” – Industry framing.

D. MindCast AI Analyses

Mechanism: Develops the MLS-governance and coordination-cost architecture that the draft imports as the mechanism by which Compass’s design choices convert MLS fragmentation and private channels into exit barriers for broker-contractors.

MCAI Lex Vision: Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part III- Coordination Costs, MLS Governance and the Compass Litigation, Coordination Architecture Defense, Expert Testimony Strategy, and the Reframing of Compass v. NWMLS (2025–2027) (Dec 2025) Shows how MLS governance and coordination costs enable Compass to turn private channels and fragmented listing visibility into de facto exit barriers for agents.

MCAI Lex Vision: Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part I, How Private Exclusives Reshape Competition and Threaten MLS Stability, A Foresight Simulation of Coordination Costs, Antitrust Exposure, and the NWMLS Litigation Trajectory (2025–2030) (Dec 2025) Explains how private exclusives destabilize MLS as shared infrastructure and create conditions for SSNDW-style labor suppression without changing nominal splits.

Application: Applies that coordination framework to this merger, prefiguring the draft’s move from foresight simulation to doctrinal translation and informing its identification of specific monopsony channels (routing stratification, SSNDW capacity, fragmentation of MLS as labor infrastructure).

MCAI Lex Vision: Compass–Anywhere, When Scale Becomes Liability, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics, Anchored in Coordination-Cost Economics (Dec 2025) Identifies how CompassAnywhere’s scale, routing stratification, and integrated Agent Operating System create monopsony capacity over broker earnings and mobility.

MCAI Lex Vision: From Open Market to Private Governance, Coordination Capture in the Compass–Anywhere Merger, Comment on Senators Warren-Wyden Letter to US DOJ and FTC (Dec 2025) Explains how Compass–Anywhere can convert shared MLS coordination into private governance through coordination capture and lock-in, using quantitative metrics such as the Coordination Capacity Index and Lock-In Probability, and links those structural risks to the Warren–Wyden letter and enforcement timing to show why pre-consummation structural intervention is more effective than post-hoc conduct remedies once coordination infrastructure has been internalized.

MCAI Lex Vision: Compass’s Coasean Coordination Problem Part II, the Litigation–Acquisition Monopolization Strategy, A Foresight Simulation of Coordination Architecture Shock, Merger Scenario Probabilities, and National MLS Fragmentation Risk (2025–2030) (Dec 2025) Connects Compass’s coordination architecture to a litigation–acquisition monopolization strategy and maps out merger-driven MLS fragmentation risk.

Chicago Series: Provides the integrated Chicago-law-and-behavioral-economics frame that the draft relies on implicitly: Coase for coordination vs. transaction costs, Becker for incentive exploitation, and Posner for efficient liability allocation, all of which underlie the LLMM metrics and remedy design.

MCAI Economics Vision: Chicago School Accelerated — The Integrated, Modernized Framework of Chicago Law and Behavioral Economics, Why Coase, Becker, and Posner Form a Single Analytical System (Dec 2025) Provides the unified Coase–Becker–Posner system for analyzing coordination costs, incentive exploitation, and efficient liability allocation in antitrust remedies.

MCAI Economics Vision: The Chicago School Accelerated Part I, Coase and Why Transaction Costs ≠ Coordination Costs, A Foresight Simulation of OpenAI’s Governance Breakdown and the Musk Multi-Entity Portfolio (Dec 2025) Clarifies why coordination costs, not just transaction costs, are the key margin of control when a platform commands MLS access, lead flow, and workflow tools.

MCAI Economics Vision: The Chicago School Accelerated Part II, Becker and the Economics of Incentive Exploitation, Incentives After Coordination Collapse: Compass and the Economics of Litigation Driven Market Control (Dec 2025) Models how a dominant firm exploits incentives after coordination collapse via lead routing, support tiering, and contract structures to extract surplus from agents.

MCAI Economics Vision: The Chicago School Accelerated Part III, Posner and the Economics of Efficient Liability Allocation, Why Behavioral Economics Transforms the Lowest-Cost Avoider Calculus in AI Hallucinations (Dec 2025) Justifies structural, self-executing remedies that lower exit costs as the efficient way to allocate liability in platform-mediated labor monopsony.

Enforcement: Demonstrates how the article’s framework can be operationalized in practice, furnishing example language, theories of harm, and remedy asks for state enforcers, which the draft then systematizes into a more general Lemley-consistent enforcement roadmap.

MCAI Lex Vision : Letter to State Attorneys General on Compass-Anywhere Merger, Request for State Regulatory Review (Dec 2025) Supplies concrete theories of harm, evidentiary asks, and remedy proposals for state enforcement against CompassAnywhere’s architectural monopsony.